History

Al Andalus

Al-Andalus refers to the Muslim-ruled Iberian Peninsula during the medieval period, from the 8th to the 15th century. It was a culturally rich and diverse region, known for its significant contributions to art, architecture, science, and philosophy. Al-Andalus was characterized by a unique blend of Islamic, Christian, and Jewish influences, and it played a pivotal role in the transmission of knowledge between the East and the West.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

8 Key excerpts on "Al Andalus"

Learn about this page

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.

- eBook - ePub

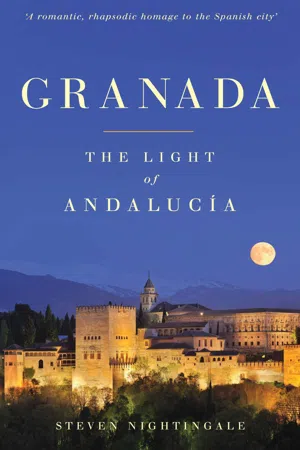

Granada

The Light of Andalucía

- Steven Nightingale(Author)

- 2015(Publication Date)

- Nicholas Brealey Publishing(Publisher)

Al-Andalus: Notes on a Hidden, Lustrous, Indispensable EraIN THE ALBAYZÍN, we lived face-to-face with the Middle Ages. The Alhambra, soaring on its promontory, had its beginning in the early 1200s. And our whole barrio had kept, through its thriving and catastrophe, the basic street pattern of a medieval village.Gabriella and I used to go whimsically about the lanes, sure that some of the ancient doors opened into another century. Sometimes we sat together before a wall of white plaster, where, as though watching a movie, we conjured the daily life of another epoch. Such fun gave us many laughs, as we rambled and whispered our way through the afternoon. But all these antics did not undo my wretched ignorance of the period.Let us define what we mean by Al-Andalus: it is the period of history spanning almost eight hundred years, from 711 to 1492, on the Iberian peninsula, under the administration of either Islamic emirs or caliphs, or Christian kings and queens. Whatever the faith of the powerful in whatever region of Iberia, Al-Andalus is a distinctive cultural space. When we arrived in Spain, I had studied the reign of Ferdinand and Isabel, their triumphant unification of Spain, and the explorations of Columbus. But I knew little about the Islamic, Christian, and Jewish leaders and even less about the scholars of the period.But the conjured movies and magic doors led me to shelves of books, and to the houses of our neighbors, and to the history of gardens and of our cherished neighborhood. And thence to the history of Al-Andalus.Just as the Albayzín is a study in unlikelihood, so the history of Al-Andalus is itself improbable; so improbable that, until recently, it hardly existed at all. Most of us learn something about medieval European history, but in general, the material covers in more depth the history of countries other than Spain. There is a simple reason for this: to study Christian Europe of the Middle Ages, you needed, principally, Latin, probably Greek, and the vernacular language of the region you studied. To study Al-Andalus, you needed not only Latin and medieval Spanish, but a mastery of Hebrew and Arabic, plus a willingness to understand the contributions of Arabic and Jewish culture. But scholars with such a sweep of languages and interests were rarely to be found, except in concept, like the saber-toothed tiger. - eBook - ePub

- (Author)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Lonely Planet(Publisher)

In 711 Tariq ibn Ziyad, the Muslim governor of Tangier, landed at Gibraltar with around 10,000 men, mostly indigenous North African Berbers. They decimated Roderic’s army, probably near the Río Guadalete in Cádiz province, and Roderic is thought to have drowned as he fled. Within a few years, the Muslims had taken over the whole Iberian Peninsula except for small areas in the Asturian mountains in the far north. The name given to the Muslim-ruled territories was Al-Andalus. From this comes the modern name of the region that was always the Islamic heartland on the peninsula – Andalucía. Al-Andalus’ frontiers shifted constantly as the Christians strove to regain territory, but until the 11th century the small Christian states developing in northern Spain were too weak to pose much of a threat to Al-Andalus.In the main cities, the Muslims built beautiful palaces, mosques and gardens, opened universities and established public bathhouses and bustling zocos (markets). The Moorish (as it’s often known) society of Al-Andalus was a mixed bag. The ruling class was composed of various Arab groups prone to factional friction. Below them was a larger group of Berbers, some of whom rebelled on numerous occasions. Jews and Christians had freedom of worship, but Christians had to pay a special tax, so most either converted to Islam or left for the Christian north. Christians living in Muslim territory were known as Mozarabs (mozárabes in Spanish); those who adopted Islam were muwallads (muladíes). Before long, Arab, Berber and local blood merged, and many Spaniards today are partly descended from medieval Muslims.Moorish Spain ReadsMoorish Spain (Richard Fletcher; 1992)The Ornament of the World (María Rosa Menocal; 2002)Andalus (Jason Webster; 2004)The Cordoban Emirate & Caliphate

The first centre of Islamic culture and power in Spain was the old Roman provincial capital Córdoba. In 750 the Umayyad dynasty of caliphs in Damascus, supreme rulers of the Muslim world, was overthrown by a group of revolutionaries, the Abbasids, who shifted the caliphate to Baghdad. One of the Umayyad family, Abd ar-Rahman, escaped the slaughter and somehow made his way to Morocco and then to Córdoba, where in 756 he set himself up as an independent emir (prince). Abd ar-Rahman I’s Umayyad dynasty kept Al-Andalus more or less unified for over 250 years. - eBook - ePub

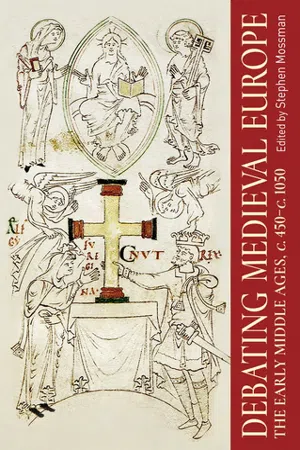

Debating medieval Europe

The early Middle Ages, c. 450– c. 1050

- Stephen Mossman(Author)

- 2020(Publication Date)

- Manchester University Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER 7Early medieval Spain, 800–1100: the Christian kingdoms and al-Andalus

Robert PortassINTRODUCTIONThe history of early medieval Spain (here shorthand for the whole of the Iberian peninsula, for the Kingdom of Portugal did not come into existence until 1139) is unlike that of the other major western European kingdoms of the period in one crucial respect: in 800 between half and two-thirds of the peninsula had been ruled for almost a century by a Muslim polity. Yet Islamic Iberia was in its own way something of an anomaly within the wider Muslim world.1 For a start, it lay on the very western fringes of the Islamic empire, presenting a series of challenges to its distant overlords. One such challenge was government and, in particular, how to implement and enforce its strictures from afar. Throughout the first half of the eighth century, the Umayyad dynasty of Damascus (Syria) managed affairs in Iberia via a series of governors (sing. wālī), at least some of whom were appointed by, or at least in consultation with, the governors of Ifrīqiya, based at Qayrawān (Tunisia).2 Political and cultural relations across the Straits of Gibraltar were to remain central to further developments, and it is as well to remind ourselves at this point of an emerging pattern that holds true for the entirety of the Middle Ages: Muslim Spain, from its beginnings, was just as much affected by relations with North Africa as it was with Islam’s political strongholds in the Arabian peninsula and the Fertile Crescent.North Africa had indeed been the springboard for the conquest of the Iberian peninsula in 711, when the Catholic Visigothic kingdom of Toledo, discussed in Paul Fouracre’s Chapter 2 , on the ‘Successor States’, was destroyed by armies composed largely of Berber troops, fighting under the banner of Islam. Later accounts make it clear that most of Visigothic Hispania fell to the conquerors within three years.3 Garrisons were established in all but the remotest corners of the peninsula, negotiations were conducted with provincial governors left in limbo by the demise of their Visigothic paymasters, and deals were soon struck so as to ensure some measure of stability between the conquerors and the conquered. These deals – more properly pacts or treaties – confirmed the protection of certain basic freedoms of the conquered peoples, including the right to go about their daily lives unmolested, in exchange for the payment of a capitation tax (jizya).4 This was a concession extended by Muslims to followers of the other Abrahamic faiths, known in Islam as ‘People of the Book’ (ahl alkitāb). Christians and Jews, therefore, were afforded the status of dhimmī - eBook - ePub

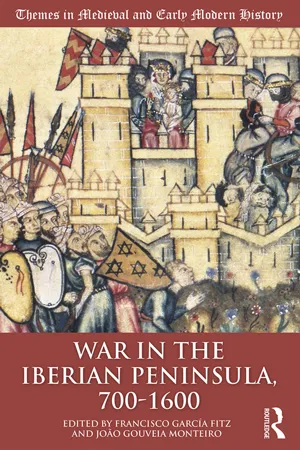

- Francisco García Fitz, João Gouveia Monteiro, Francisco García Fitz, João Gouveia Monteiro(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

1 Al-AndalusJavier Albarrán 1Political outline

The conquest of al-Andalus and the first steps

The history of al-Andalus begins in the year 711, when, commanding an army consisting mostly of Berbers and some Arabs, Tariq b. Ziyad crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and initiated the conquest of the Iberian Peninsula at the service of Musa b. Nusayr, the Umayyad ruler of the province of Ifriqiya. Apparently, Tariq achieved a decisive victory against the Visigoth King Rodrigo next to the River Guadalete, although not all scholars agree with this location of the battle. Soon, barely offering any resistance due to the state of decomposition of the Visigothic kingdom, important cities fell one by one, such as Seville, Cordova and Toledo, the Visigothic capital. The success of the expedition led Musa b. Nusayr to intervene directly, and within a few years practically the entire Iberian Peninsula, and even southern France, had been conquered. Al-Andalus was thus established as an additional region of the Umayyad Caliphate of Damascus, dependent on the province of Ifriqiya (Manzano 2006: 29–53).The Umayyad Emirate of al-Andalus

After the triumph of the Abbasid revolution in the East and the disappearance of the Umayyad Caliphate of Damascus (750), one of the few survivors of the outgoing dynasty, ‘Abd al-Rahman, managed to reach al-Andalus and proclaim himself emir in the year 756. Thus began the period known as the independent Umayyad emirate of al-Andalus, with its capital at Cordova. During this period, Islamic power consolidated in the Iberian Peninsula and the islamization and arabization process began, which did not reach its apex until approximately the 11th century. A few mountainous regions north of al-Andalus escaped the control of the Umayyad emirs, where, after the legendary Battle of Covadonga (722), the Asturian kingdom would first come into existence. Cordova carried out numerous campaigns against these northern Christians, with the main goal being to prevent them from advancing southwards. - eBook - ePub

- Pierre Cachia(Author)

- 2017(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

It yet remains to be stressed that what the Andalusians handed down to their Romance successors was not their classical tradition—not their monorhyme odes with their succession of conventional themes, not their trope-laden prose —but imaginative tales, strophic forms of poetry and perhaps the particularly refined lyricism of their love-songs. They were features remarkably close to those which have been held to distinguish their literature from that of their coreligionists of the East. They were also, in no small part, features that belonged to popular literature or derived from it.This is consistent with a total picture of Islamic Spain in which the literature of the élite, strengthened by patronage, sought to perpetuate traditional standards no doubt valid but derived, and reaped the reward of steadfastness in glittering masterpieces. But co-existing with it, penetrating it only partially but more profoundly than in other lands where Arabic held sway, was another literature which was the natural expression of a population ethnically and culturally mixed, in which the Arab element gave and took, merged and moulded, was stimulated and in turn elaborated and developed. The fusion of these ethnic and cultural elements produced the distinctive features of Andalusia's literature; it also favoured their survival.Andalusian literature was like the progeny of an expatriate aristocrat who had had two wives: one a free woman of his own race and background, the other a local bondwoman. The sons of the first wife shone best at court; those of the bondwoman were more adaptable, even when political change swept away their father's privilege.4. The Art of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth CenturiesDespite the worsening political situation in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries the artistic tradition of Islamic Spain was still alive and indeed producing some of its greatest works. It may be regarded as having split up into two branches: Mudejar art, and the art of Granada (or Grenadine art).The Mudejars, as already explained, were the Muslims who elected to remain in territories ruled by Christians. Their numbers were considerable in certain areas, and it was through this new form of association of Muslim and Christian that much of the culture of al-Andalus passed to Christian Spain, or rather was assimilated by Christian Spain in its expansion. This coming together of two societies in what is almost a single cultural organism is what is sometimes called "the Mudejar fact". Mudejar art, however, is not simply the art produced by the Mudejars, but rather the art arising out of this new cultural unity. It was an art which continued the tradition of Islamic art from the independent Muslim kingdoms, yet was genuinely at home in this new composite Christian-dominated society. So much was this the case that the craftsmen who carried out the work were sometimes Christian and sometimes Muslims from independent Granada, and yet the work had the Mudejar stamp; while Mudejar craftsmen who went elsewhere produced work in other styles. - eBook - ePub

- Abraham Kuyper, James D. Bratt, James D. Bratt(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Lexham Press(Publisher)

CHAPTER 9 SPAIN THE MOORISH ERA IN SPANISH HISTORY 1 The domination of the Arabs and Moors over Spain, which began in 710 and ended only in 1492 with the fall of Granada, was no doubt a blessing to Spain in many ways. In this respect, it is very similar to the Roman dominion that persisted from 180 BC to 466 AD. As in Cairo and Fez, Islam introduced a high state of development from the very outset. With the use of irrigation, agriculture flourished in the dry regions, bringing these areas to unprecedented levels of development. Industry flourished as never before. Higher scholarship entered with extraordinary speed, and among the arts, at least architecture was strongly promoted. Especially in the fields of philosophy and medicine the Jews vied with the Arabs to be the masters of Europe, and possibly to push both Baghdad and Cairo into the background. Money flowed like water, and thanks to this flood, wealth as in the old days of Roman rule returned to all the cities, now enhanced with an Eastern glow. Commercial connections were established with all of Europe, and in more than one European court the physician to the prince was a Jewish specialist from Córdoba. In this respect there was no persecution of Christians to speak of. 2 In fact, it was preferred that Christians not convert since that would diminish tax revenue. General toleration was the rule, and so religious differences faded into the background. Already in Damascus, caliphs had been far from strict in their teaching; likewise, those in Córdoba were not zealots in the least. Nor did Christians oppose this state of affairs. People in the upper circles mingled together for wealth, profit, and learning. They intermarried—Christian, Jew, and Muslim alike. Visiting the synagogue in Toledo was quite the fashion for a time among the Christian upper classes - eBook - ePub

Mozarabs in Medieval and Early Modern Spain

Identities and Influences

- Richard Hitchcock(Author)

- 2016(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

58 It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that, after the invasion, the squabbling amongst a tiny remnant of Visigoths was of little consequence to the indigenous population of the Peninsula. The change of overlordship conferred upon them a privileged status, which they came to appreciate, through the gradual establishment of Islam over two-and-a-half centuries.1 For example, David Hannay, Spain , London: T.C. Jack and E.C. Jack, 1917: ‘The desire to extend the dominion of their faith was motive enough for the Mahometans’, p. 27.2 The Holy Qur-án , containing the Arabic text with English translation and commentary by Maulvi Muhammad Ali (Woking: The Islamic Review, 1917), pp. 414 and 721. In Spanish,Sū ra25, v. 54, the ambiguity is removed: ‘No cedas a los infieles; pero combátelos vigorosamente con este libro’ [Mahoma, El Corán , Madrid: Biblioteca DM, 1995, p. 251]. Also relevant isSū ra29, v. 6: ‘And whoever strives hard, he strives only for his own soul.’ Ali comments: ‘The suffering of persecution and torture at the hands of their enemies for the sake of their faith was no less ajihā dof the Muslims at Mecca than their fighting in defence of Islam at Medina’ (p. 775).3 A differing view is expressed by Mahmoud Makki in his essay: ‘The political history of Al-Andalus (92/711-897/1492)’, in The Legacy of Muslim Spain , Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1992, pp. 3-87, where he mentions that ‘a number of the governors of al-Andalus conducted a policy of Islamic Holy War beyond the Pyrenees’ (p. 15).4 Stanley Lane-Poole, The Moors in Spain , London: T. Fisher Unwin, 5th edn, with the collaboration of Arthur Gilman, MA, 1893: ‘An issue momentous to Europe was to be decided, and the conflict that ensued has rightly been numbered among the fifteen decisive battles of the world. The question to be judged by force of arms was whether Europe was to be Christian or Mohammedan – whether the future Nôtre Dame was to be a church or a mosque’ (p. 29). D.M. Dunlop, in his Arab Civilization to A.D. 1500 - eBook - ePub

Caliphs and Kings

Spain, 796-1031

- Roger Collins(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Wiley-Blackwell(Publisher)

in the mid-tenth century, to previous periods in the history of al-Andalus, or to extend them geographically to encompass the rest of its towns and cities in this period, but this would be entirely wrong. Before the second quarter of the tenth century this was very much the “wild west” of the Islamic world, offering few inducements for scholars and artists from outside to come in search of patronage. It cannot be too strongly emphasized that our evidence for the high artistic and material culture of al-Andalus under Umayyad rule is confined almost exclusively to Córdoba and to the period extending from about 930 to about 980.This is not to say that there had not been contact with more sophisticated Islamic societies in the eastern Mediterranean and beyond, or that exotic migrants did not occasionally arrive in al-Andalus bringing new ideas and styles with them. A particular case is that of Ziry b, whose proper name was Ab al- asan ‘Ali b. Naf ’ al-Bagdadi, a musician of Persian mawali origin, who arrived in Córdoba early in the reign of ‘Abd al-Ra m n II (822–852). His presence at the am r's court made so much of a stir that several pages were devoted to him by Ibn ayy n, quoting from A mad al-Rasi and also an anonymous “Book of notes on Ziry b.”41 His fame came from being the pupil of “the best singer of his day,” who then became jealous of his disciple's success in performing before the ‘Abb sid caliph Harun al-Rashid, forcing him to leave Baghdad to seek his proverbial “fame and fortune” elsewhere. Despite arousing yet more jealousy in Córdoba because of the size of the pensions he and his sons received from the am r, he managed to introduce some practices hitherto unknown in the west, such as the eating of asparagus and the use of deodorant.42 It was the rarity of such sophisticates in al-Andalus not their frequency that kept the memory of Ziry b alive, with books being written about him over a century after his death.The same caution in avoiding over-evaluating the wider significance of individual cases applies to the intellectual culture of Umayyad al-Andalus. Just as we must not assume that mid-tenth century Córdoba was representative of the smaller towns and cities of al-Andalus, so it is important not to project backwards into the Umayyad period the literary and scientific milieu of the succeeding Ta’ifa period. The Umayyad regime was generally cautious and conservative when it came to its relations with the ulama on whose approval it depended. The consistent promotion by the dynasty of the ideas of the Malikites, one of the most rigorous and austere of the schools of Islamic jurisprudence, was not a matter of chance. The am rs were unbending in their application of judicial penalties, such as crucifixion for the promotion of heterodox ideas amongst Muslims, however highly placed in society. This, for example, was the fate of Yahya b. Zakariyy , a cousin of one of ‘Abd al-Ra m n II's favorite aunts, despite her pleas for clemency.43