eBook - ePub

The Exploratorium Science Snackbook

Cook Up Over 100 Hands-On Science Exhibits from Everyday Materials

This is a test

Buch teilen

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

The Exploratorium Science Snackbook

Cook Up Over 100 Hands-On Science Exhibits from Everyday Materials

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Kids and teachers can build their own science projects based on exhibits from San Francisco's premiere science museum

This revised and updated edition offers instructions for building junior versions, or "snacks, " of the famed Exploratorium's exhibits. The snacks, designed by science teachers, can be used as demonstrations, labs, or as student science projects and all 100 projects are easy to build from common materials. The Exploratorium, a renowned hands-on science museum founded by physicist and educator Frank Oppenheimer, is noted for its interactive exhibits that richly illustrate scientific concepts and stimulate learning.

- Offers a step-by-step guide for building dynamic science projects and exhibits

- Includes tips for creating projects made from easy-to-assembly items

- Thoroughly revised and updated, including new "snacks, " images, and references

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist The Exploratorium Science Snackbook als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu The Exploratorium Science Snackbook von im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Education & Teaching Science & Technology. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

PART ONE

THE CHESHIRE CAT AND OTHER EYE-POPPING EXPLORATIONS OF HOW WE SEE THE WORLD

How do you see the world around you? You open your eyes and there it is: your room, your desk, the pictures on the walls, the trees outside your window.

When you take a look at the world, here’s what’s happening: Light is bouncing off the pictures, the trees, and all the things out there in the world. Some of that light gets into your eye. This light shines through the cornea, the tough, clear covering over the front of your eye, and then through the pupil, the dark hole in the center of your iris, the colored part of your eye. Your eye’s lens focuses this light to make an image on your retina, a thin layer of light-sensitive cells that lines the back of your eyeball. The light-sensitive cells of the retina signal the brain, and the brain creates a mental image. Finally, you see the world “out there.”

People have compared the eye to a film-loaded camera—and for good reason. Both your eye and a camera have adjustable openings that let in light: the pupil of your eye and the aperture of a camera. Both focus the light to make an image on a light-sensitive screen: the retina of your eye and the film of a camera.

But unlike a camera, your eye doesn’t just passively record the image it receives. Working together, your eyes and brain decide what to see and how to see it. They fill in gaps in your visual field, taking limited information and creating a complete picture. They interpret the limited and distorted images that they receive and try to make sense of the world out there, often using past experience as a guide. They constantly filter out and ignore extraneous information.

You don’t believe it? Then close one eye and take a look at the tip of your nose. You can see it clearly if you think about it. It’s always in your view. Open both eyes and you can still see it, a shadowy protuberance in the center of your visual field. If you think about the tip of your nose, you can see it—but most of the time you don’t notice it (even though it’s as plain as the nose on your face).

The experiments in this section will show you some other sights you usually don’t notice. Some experiments, such as Blind Spot, Pupil, and Afterimage, will help you understand more about how your eye works—its abilities and limitations. Others, like Vanna and Far-Out Corners, show how prior experience often influences perception: how what you “see” may not be what you “get.” Still others, like Persistence of Vision and Jacques Cousteau in Seashells, demonstrate that your eyes and brain work together to make a picture of the world. Finally, some show how your eyes and brain can make mistakes in their interpretation of the world—mistakes that create optical illusions, deceptive pictures that fool your eyes.

Taken together, the experiments in this section let you explore visual perception, a fascinating interdisciplinary topic where biology and psychology overlap.

AFTERIMAGE

A flash of light prints a lingering image in your eye.

Materials

• Opaque black tape (such as electrical tape)

• White paper

• A flashlight

Introduction

After looking at something bright, such as a lamp or a camera’s flash, you may continue to see an image of that object when you look away. This lingering visual impression is called an afterimage.

Assembly

(15 minutes or less)

1. Tape a piece of white paper over a flashlight lens.

2. Cover all but the center of the white paper with strips of opaque tape.

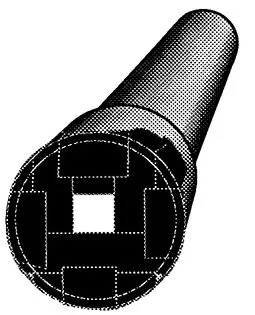

3. In the center of the paper, leave an area uncovered where the light can shine through the paper. This area should be a square, a triangle, or some other simple, recognizable shape.

To Do and Notice

(15 minutes or more)

In a darkened room, turn on the flashlight, hold it at arm’s length, and shine it into your eyes. Stare at one point of the brightly lit shape for about 30 seconds. Then stare at a blank wall and blink a few times. Notice the shape and color of the image you see.

Try again—first focusing on the palm of your hand and then focusing on a wall some distance from you. Compare the size of the image you see in your hand to the image you see on the wall.

Close your left eye and stare at the bright image with your right eye. Then close your right eye and look at the wall with your left eye. You will not see an afterimage.

Etcetera

For up to 30 minutes after you walk into a dark room, your eyes are adapting. At the end of this time, your eyes may be up to 10,000 times more sensitive to light than they were when you entered the room. We call this improved ability to see “night vision.” It’s caused by the chemical rhodopsin in the rods of your retina. Rhodopsin, popularly called visual purple, is a light-sensitive chemical composed of retinal (a derivative of vitamin A) and the protein opsin.

You can use the increased presence of rhodopsin to take “afterimage photographs” of the world. Here’s how:

Cover your eyes to allow them to adapt to the dark. Be careful that you do not press on your eyeballs. It will take at least 10 minutes to store up enough visual purple to take a “snapshot.” When enough time has elapsed, uncover your eyes. Open your eyes and look at a well-lit scene for half a second (just long enough to focus on the scene), then close and cover your eyes again. You should see a detailed picture of the scene in purple and black. After a while, the image will reverse to black and purple. You can take several “snapshots” after each 10-minute adaptation period.

What’s Going On?

You see because light enters your eyes and produces chemical changes in the retina, the light-sensitive lining at the back of your eye. Prolonged stimulation by a bright image (here, the light source) desensitizes part of the retina. When you look at the blank wall, light reflecting from the wall shines onto your retina. The area of the retina that was desensitized by the bright image does not respond as well to this new light input as the rest of the retina. Instead, this area appears as a negative afterimage, a dark area that matches the original shape. The afterimage may remain for...