eBook - ePub

Waste Management Practices

Municipal, Hazardous, and Industrial, Second Edition

John Pichtel

This is a test

- 682 Seiten

- English

- ePUB (handyfreundlich)

- Über iOS und Android verfügbar

eBook - ePub

Waste Management Practices

Municipal, Hazardous, and Industrial, Second Edition

John Pichtel

Angaben zum Buch

Buchvorschau

Inhaltsverzeichnis

Quellenangaben

Über dieses Buch

Waste Management Practices: Municipal, Hazardous, and Industrial, Second Edition addresses the three main categories of wastes (hazardous, municipal, and "special" wastes) covered under federal regulation outlined in the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), an established framework for managing the generation, transportation, treat

Häufig gestellte Fragen

Wie kann ich mein Abo kündigen?

Gehe einfach zum Kontobereich in den Einstellungen und klicke auf „Abo kündigen“ – ganz einfach. Nachdem du gekündigt hast, bleibt deine Mitgliedschaft für den verbleibenden Abozeitraum, den du bereits bezahlt hast, aktiv. Mehr Informationen hier.

(Wie) Kann ich Bücher herunterladen?

Derzeit stehen all unsere auf Mobilgeräte reagierenden ePub-Bücher zum Download über die App zur Verfügung. Die meisten unserer PDFs stehen ebenfalls zum Download bereit; wir arbeiten daran, auch die übrigen PDFs zum Download anzubieten, bei denen dies aktuell noch nicht möglich ist. Weitere Informationen hier.

Welcher Unterschied besteht bei den Preisen zwischen den Aboplänen?

Mit beiden Aboplänen erhältst du vollen Zugang zur Bibliothek und allen Funktionen von Perlego. Die einzigen Unterschiede bestehen im Preis und dem Abozeitraum: Mit dem Jahresabo sparst du auf 12 Monate gerechnet im Vergleich zum Monatsabo rund 30 %.

Was ist Perlego?

Wir sind ein Online-Abodienst für Lehrbücher, bei dem du für weniger als den Preis eines einzelnen Buches pro Monat Zugang zu einer ganzen Online-Bibliothek erhältst. Mit über 1 Million Büchern zu über 1.000 verschiedenen Themen haben wir bestimmt alles, was du brauchst! Weitere Informationen hier.

Unterstützt Perlego Text-zu-Sprache?

Achte auf das Symbol zum Vorlesen in deinem nächsten Buch, um zu sehen, ob du es dir auch anhören kannst. Bei diesem Tool wird dir Text laut vorgelesen, wobei der Text beim Vorlesen auch grafisch hervorgehoben wird. Du kannst das Vorlesen jederzeit anhalten, beschleunigen und verlangsamen. Weitere Informationen hier.

Ist Waste Management Practices als Online-PDF/ePub verfügbar?

Ja, du hast Zugang zu Waste Management Practices von John Pichtel im PDF- und/oder ePub-Format sowie zu anderen beliebten Büchern aus Law & Environmental Law. Aus unserem Katalog stehen dir über 1 Million Bücher zur Verfügung.

Information

Part I

Historical and Regulatory Development

Solid waste is a generic term that describes those materials that are of little or no value to humans; in this context, disposal may be preferred over usage. Solid wastes have also been termed municipal solid waste, domestic waste, and household waste. As we shall see, however, the regulatory definition of solid waste is an inclusive one, incorporating hazardous wastes, nonhazardous industrial wastes, and sewage sludges from wastewater treatment plants, along with garbage, rubbish, and trash. However, not all of the above wastes are necessarily managed in the same manner or disposed in the same facility. The definition only serves as a starting point for more detailed management decisions.

Until recently, waste was given a low priority in the conference rooms of municipal, state, and federal offices responsible for public health and safety. Waste management has since emerged as an urgent, immediate concern for industrial societies—a result of generation of massive waste quantities as a consequence of economic growth and lifestyle choices. Concomitant concerns have arisen regarding the inherent hazards of many such materials, as well as the cost of their overall management and disposal.

Over the past three decades, significant legislation has been enacted for the purpose of protecting humans and the environment from the effects of improper waste management and disposal. In addition, a wide range of economic incentives (e.g., grants and tax breaks) have been made available to municipalities, corporations, and universities to support waste reduction, recycling, and other applications of an integrated waste management program. Some have proven highly successful.

Part 1 provides the reader with a framework for the management of many types of wastes. The Introduction is followed by a history of waste management and then a discussion of regulatory development in waste management.

1 Introduction

Conspicuous consumption of valuable goods is a means of reputability to the gentleman of leisure.

Thorstein Veblen

The Theory of the Leisure Class, 1899

As recently as a few decades ago in the United States, the chemical, physical, and biological properties of the municipal solid waste stream were of little or no concern to the local hauling firm, the city council, or the citizens who generated the waste. Similarly, little thought was given to the total quantities of waste produced. Waste volumes may have appeared fairly consistent from year to year, since few measurements were made. Wastes were transported to the local landfill or perhaps the town dump alongside the river for convenient final disposal. The primary concerns regarding waste management were, at that time, aesthetic and economic, that is, removing nuisance materials from the curb or the dumpster quickly and conveniently, and at the lowest possible cost.

By the late 1980s, however, several events were pivotal in alerting Americans to the fact that the present waste management system was not working. When we threw something away, there was really no “away”:

- 1. The Islip Garbage Barge. On March 22, 1987, the Mobro 4000 left Islip, Long Island, NY, with another load of about 3100 tons of garbage for transfer to an incinerator in Morehead City, NC. Upon learning that the barge may be carrying medical waste, concerns were raised by the receiving facility about the presence of infectious materials on board, and the Mobro was refused entry. From March through July, the barge was turned away by six states and several countries in Central America and the Caribbean (Figure 1.1). The Mexican Navy intercepted the barge in the Yucatan Channel, forbidding it from entering Mexican waters. The ongoing trials of the hapless barge were regular features on many evening news programs. The waste was finally incinerated in Brooklyn, NY, and the ash was disposed in the Islip area.

- 2. Beach washups. In 1988, medical wastes began to wash up on the beaches of New York and New Jersey. In 1990, the same phenomenon occurred on the West Coast. Popular beaches along the East Coast and in California closed because of potentially dangerous public health conditions. Outraged officials demanded to know the sources of the pollution, arranged for cleanups, and attempted to assure the public that the chances of this debris causing illness were highly remote; however, public fears of possible contact with hepatitis B and HIV viruses led to a concomitant collapse in local tourist industries.

- 3. The Khian Sea. This cargo ship left Philadelphia, PA, in September 1986, carrying 15,000 tons of ash from the city’s municipal waste incinerator for transfer to a landfill (Figure 1.2). It was soon suspected, however, that the ash contained highly toxic chlorinated dibenzodioxins; as a result, the ship was turned away from ports for 2 years, during which it wandered the high seas searching for a haven for its toxic cargo (Holland Sentinel 2002). About 4000 tons of the ash was dumped on a beach in Haiti near the port of Gonaives. An agreement was arranged 10 years later for the return of the ash to the United States.

- 4. The plight of the sanitary landfill. The mainstay for convenient waste disposal in the United States is becoming increasingly difficult and costly to operate. Stringent and comprehensive regulations for landfill construction, operation, and final closure were forcing underperforming landfills to shut down. Those facilities that remained in operation were compelled to charge higher tipping (i.e., disposal) fees, often in the form of increased municipal taxes.

- 5. Love Canal. This event galvanized American society into an awareness of the acute problems that can result from mismanaged wastes (particularly hazardous wastes). In the 1940s and 1950s, the Hooker Chemical Company of Niagara Falls, NY, disposed over 100,000 tons of hazardous petrochemical wastes, many in liquid form, in several sites around the city. Wastes were placed in the abandoned Love Canal and also in a huge unlined pit on Hooker’s property. By the mid-1970s, chemicals had migrated from the disposal sites. Land subsided in areas where containers deteriorated, noxious fumes were generated, and toxic liquids seeped into basements, surface soil, and water. The incidence of cancer, respiratory ailments, and certain birth defects was well above the national average. A public health emergency was declared for the Love Canal area, many homes directly adjacent to the old canal were purchased with government funds, and those residents were evacuated. Numerous suits were brought against Hooker Chemical, both by the U.S. government and by local citizens. At the time, however, there was simply no law that assigned liability to responsible parties in the event of severe land contamination.

With greatly enhanced environmental awareness by U.S. citizenry, and with public health, environmental as well as economic concerns, a paramount focus of many municipalities, a proactive and integrated waste management strategy has evolved. The new mindset embraces waste reduction, reuse, resource recovery, biological processing, and incineration, in addition to conventional land disposal. Given these new priorities, the importance of documenting the composition and quantities of municipal solid wastes (MSWs) produced, and ensuring its proper management (including storage, collection, segregation, transport, processing, treatment, disposal, recordkeeping, and so on) within a community, city, or nation cannot be overstated.

1.1 DEFINITION OF A SOLID WASTE

We can loosely define solid waste as a solid material possessing a negative economic value, which suggests that it is cheaper to discard than to use. Volume 40 of The U.S. Code of Federal Regulations (40 CFR 240.101) defines a solid waste as:

garbage, refuse, sludges, and other discarded solid materials resulting from industrial and commercial operations and from community activities. It does not include solids or dissolved material in domestic sewage or other significant pollutants in water resources, such as silt, dissolved or suspended solids in industrial wastewater effluents, dissolved materials in irrigation return flows or other common water pollutants.

1.2 CATEGORIES OF WASTES

American consumers, manufacturers, utilities, and industries generate a wide spectrum of wastes possessing drastically different chemical and physical properties. In order to implement cost- effective management strategies that are beneficial to public health and the environment, it is practical to classify wastes. For example, wastes can be designated by generator type, that is, the source or industry that generates the waste stream. Some major classes of waste include:

- • Municipal

- • Hazardous

- • Industrial

- • Medical

- • Universal

- • Construction and demolition

- • Radioactive

- • Mining

- • Agricultural

In the United States, most of the waste groupings listed above are indeed managed separately, as most are regulated under separate sets of federal and state regulations.

1.2.1 Municipal Solid Waste

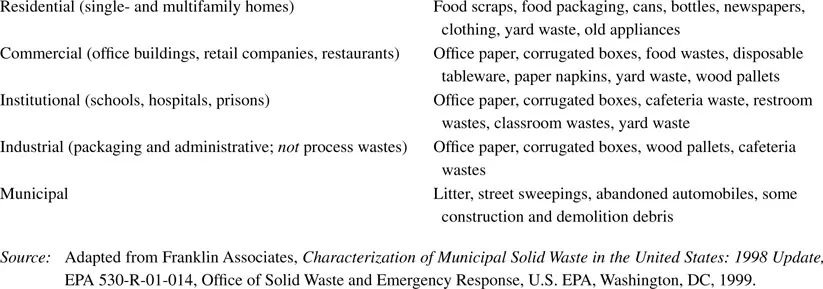

Municipal solid waste (MSW), also known as domestic waste or household waste, is generated within a community from several sources, and not simply by the individual consumer or household. MSW arises from residential, commercial, institutional, industrial, and municipal origins. Examples of the types of MSW generated from each major source are listed in Table 1.1.

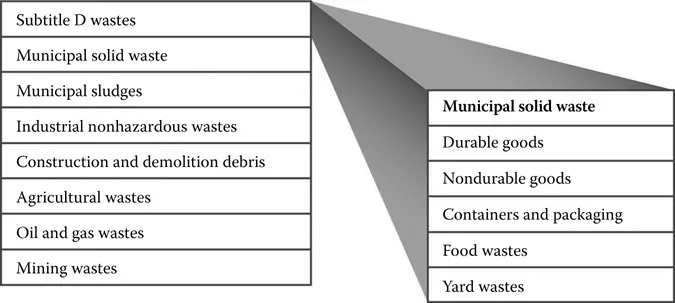

Municipal Solid Waste generation as a Function of Source

Municipal wastes are extremely heterogeneous and include durable goods (e.g., appliances), nondurable goods (newspapers, office paper), packaging and containers, food wastes, yard wastes, and miscellaneous inorganic wastes (Figure 1.3). For ease of visualization, MSW is often divided into two categories: garbage and rubbish. ...