1 | THE IDEA OF THE FABRICATION

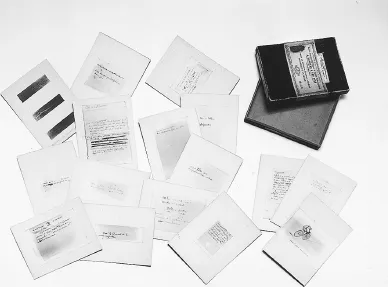

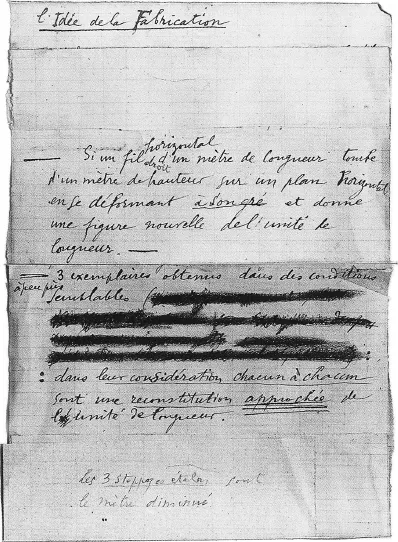

Duchamp’s idea for the fabrication of the 3 Standard Stoppages is written on a piece of notepaper in the “Box of 1914.” The latter was originally a box for photographic plates, measuring 18 x 28 cm, in which Duchamp collected photographic reproductions of the manuscripts of fifteen sketched ideas and a drawing (see fig. 1.1).1 The note reads as follows: “The Idea of the Fabrication: If a straight horizontal thread one meter long falls from a height of one meter on to a horizontal plane distorting itself as it pleases and creates a new shape of the measure of length.—3 patterns obtained in more or less similar conditions: considered in their relation to one another they are an approximate reconstitution of the measure of length” (see fig. 1.2).2 On an additional slip of paper pasted to the bottom of the notepaper is written: “The 3 Standard Stoppages are the meter diminished.” The first sentence of this “idea of the fabrication” and the note “3 Standard Stoppages: Canned chance. 1914” were published by Duchamp in the box La Mariée mise à nu par ses Célibataires, même in 1934. Known as the Green Box, it contained ninety-four facsimile notes and reproductions of studies and paintings for the Large Glass.3

The succinctness of Duchamp’s note awakens the impression that in 1913 he suddenly had the idea of changing the form of the revered platinum-iridium standard meter (kept in the Pavillon de Breteuil in Sèvres, near Paris) in an unusual experiment using three pieces of thread and, in so doing, transforming this standard measure, valid in vast parts of the world, into a random variable. His numerous descriptions, given after 1945, of his method of conducting the experiment bear out this impression. In his conversations with the art critic Pierre Cabanne, published in Paris in 1967, Duchamp says:

Fig. 1.1 Duchamp, The Box of 1914. Cardboard box for glass negatives “A. Lumière & ses Frères” with sixteen photographic reproductions of fifteen manuscript notes and one drawing, mounted on fifteen mat boards (25 x 18.5 cm).

Source: Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Alexina Duchamp, 1991. © Succession Marcel Duchamp/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2008.

The idea of ‘chance’,[4] which many people were thinking about at the time, struck me too. The intention consisted above all in forgetting the hand, since, fundamentally, even your hand is chance. Pure chance interested me as a way of going against logical reality: to put something on a canvas, on a bit of paper, to associate the idea of a perpendicular thread a meter long falling from the height of one meter onto a horizontal plane, making its own deformation. This amused me. It’s always the idea of ‘amusement’ which causes me to do things, and repeated three times.... My ‘Three Standard Stoppages’ is produced by three separate experiments, and the form of each one is slightly different. I keep the line, and I have a deformed meter. It’s a ‘canned meter’, so to speak, canned chance.5

Fig. 1.2 Duchamp, “The Idea of the Fabrication,” note from The Box of 1914.

Source: Philadelphia Museum of Art, Gift of Alexina Duchamp, 1991. © Succession Marcel Duchamp/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2008.

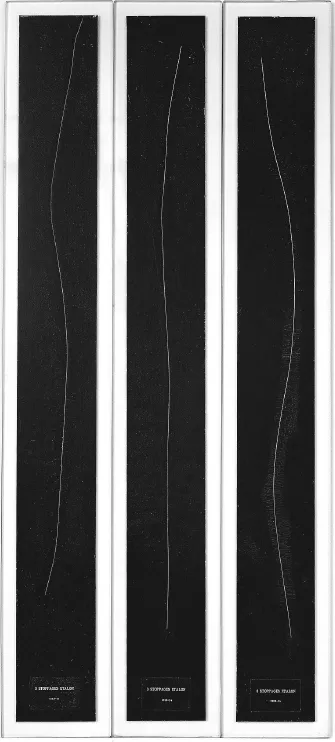

According to Duchamp, this at once pseudoscientific and artistic experiment was performed as follows: From a height of one meter, three white threads, each one meter long and held straight and horizontal, were each dropped onto three narrow canvases. The thin threads were then fixed in position by means of varnish. Thus three lines, each following a different course, appeared on the canvases, lines that were not drawn by hand but, rather, created purely by chance. Moreover, they were lines that made no reference to any figure in the outside world. Indeed, they were totally self-referential, leading a material existence as threads independently of anything existing beyond the image. On each of the three vertically held canvases Duchamp then glued a leather label bearing, in golden, embossed letters, the inscription: “3 STOPPAGES ETALON, 1913–14” (see fig. 1.3). In none of his many descriptions of this experiment does Duchamp say that the canvases are painted in a dark Prussian blue; nor does he mention the fact that the threads are not only fixed with varnish but also stitched through the canvas at both ends and are therefore actually longer than one meter, the surplus ends likewise being fixed with varnish to the rear sides of the three canvases and measuring anything between 5.5 and 12.5 cm;6 nor does he at any time say that in 1936 he fundamentally altered the appearance of this work. Our first task, therefore, will be to examine and, if possible, resolve the contradiction between the material appearance of the 3 Standard Stoppages and the “idea of the fabrication” on which it was based.

Fig. 1.3 [opposite] Duchamp, 3 Standard Stoppages, 1913–1914. Three white threads glued to three painted canvas strips (120 x 13.3 cm), each mounted on a glass panel (125.4 x 18.4 cm).

Source: The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Katherine S. Dreier Bequest, 1953. © Succession Marcel Duchamp/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2008. Digital image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY.

2 | THE 3 STANDARD STOPPAGES IN THE CONTEXT OF THE LARGE GLASS

Like everything produced by Duchamp between the years of 1913 and 1915, the 3 Standard Stoppages were a by-product of his preoccupation with his main work, the large-format glass painting La Mariée mise à nu par ses Célibataires, même (see fig. 2.1). A strenuous tour of the collections of the public art museums of Basel, Munich, Dresden, Leipzig, Berlin, Prague, and Vienna during a three months’ stay in Munich in the summer of 1912 had inspired the then only twenty-five-year-old artist to turn his back on the prevailing avant-garde tendency toward a deliterarization of painting and “to put painting once again in the service of the mind.”1 “Art or anti-art? was the question I asked when I returned from Munich in 1912 and decided to abandon pure painting or painting for its own sake. I thought of introducing elements alien to painting as the only way out of a pictorial and chromatic dead end.”2 Duchamp’s intense confrontation over only a few months with many of the most significant masterpieces of Western painting had taught him that “in fact until the last hundred years all painting had been literary or religious; it had all been at the service of the mind.”3 In contemporary painting, on the other hand, the medium itself had become the focal point of interest. “There was no thought of anything beyond the physical side of painting. No notion of freedom was taught. No philosophical outlook was introduced.”4Looking back at the fruits of his stay in Munich, Duchamp concluded that the painters of the Renaissance and the baroque were not interested in the paint tube itself but rather “in the idea of expressing the divine in one form or another. Without wanting to do the same, I maintain that pure painting as an aim in itself is of no import.”5 The young Duchamp took upon himself the risk of searching for a completely new approach for the modern painter, an approach far removed from both that of the Cubists and that of pure, abstract painting in the style of Kandinsky, which Duchamp had seen in Munich. This new approach would steer him toward a renewed literarization and intellectualization of painting via, and beyond, his admired models, Odilon Redon and Arnold Böcklin.6

And so it was that he took the bold decision to do the same as the great masters of the past and create a large-format painting in tune with the most advanced ideas of his time: The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even. Needing to familiarize himself with these ideas, Duchamp withdrew from the hustle and bustle of the Parisian art scene, ceased to exhibit, enrolled in a course on librarianship at the Sorbonne, and, in November 1913, took on employment with the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, where in his spare time—and according to him there was plenty of it—he pursued theoretical studies in the fields of geometry, philosophy, science, and perspective.7 The theme of his large-format painting had already crystallized out of a series of drawings and paintings in Munich and was just as “classical” as Duchamp’s aim to “put painting once again in the service of the mind.”8 Prepared over a period of two years with countless literary drafts, sketches, and drawn and partially painted studies, it was to be a complex modern allegory of love. His chosen mode of representation for the erotic relations between the sexes, which were doubtless based on his own experiences and emotions, could not have been more sober and impersonal: mechanical drawing. The entire scenario took the form of a fantasy machine projected onto a glass support, its components and mode of operation remaining undecipherable for the viewer until 1934, when Duchamp published the preparatory notes and studies (in the aforementioned Green Box) as a literary counterpart to the painting, a publication that had been planned from the beginning. However, the “commentaries” on the figures and forms depicted in the Large Glass were anything but explanatory. No less ambiguous or freely interpretable than the visual forms in the glass painting itself, these commentaries, couched in the metaphorical language of psychologized physics and chemistry, portrayed love as an erotic funfair.

Fig. 2.1 Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even,...