Technology & Engineering

Eiffel Tower

The Eiffel Tower is a wrought-iron lattice structure located in Paris, France. It was designed by Gustave Eiffel and completed in 1889 as the entrance arch for the 1889 World's Fair. Standing at 1,063 feet, it was the tallest man-made structure in the world until the completion of the Chrysler Building in New York City in 1930.

Written by Perlego with AI-assistance

5 Key excerpts on "Eiffel Tower"

Learn about this page

Index pages curate the most relevant extracts from our library of academic textbooks. They’ve been created using an in-house natural language model (NLM), each adding context and meaning to key research topics.

- eBook - ePub

- Robert M. Vogel(Author)

- 2010(Publication Date)

- Perlego(Publisher)

The great confidence of the Tower’s builder in his own engineering ability can be fully appreciated, however, only when notice is taken of one exceptional way in which the project differed from works of earlier periods as well as from contemporary ones. In almost every case, these other works had evolved, in a natural and progressive way, from a fundamental concept firmly based upon precedent. This was true of such notable structures of the time as the Brooklyn Bridge and, to a lesser extent, the Forth Bridge. For the design of his tower, there was virtually no experience in structural history from which Eiffel could draw other than a series of high piers that his own firm had designed earlier for railway bridges. It was these designs that led Eiffel to consider the practicality of iron structures of extreme height.Larger ImageFigure 1.—The Eiffel Tower at the time of the Universal Exposition of 1889 at Paris. (From La Nature, June 29, 1889, vol. 17, p. 73.)Figure 2.—Gustave Eiffel (1832-1923). (From Gustave Eiffel, La Tour de Trois Cents Mètres, Paris, 1900, frontispiece.)There was, it is true, some inspiration to be found in the paper projects of several earlier designers—themselves inspired by that compulsion which throughout history seems to have driven men to attempt the erection of magnificently high structures.One such inspiration was a proposal made in 1832 by the celebrated but eccentric Welsh engineer Richard Trevithick to erect a 1,000-foot, conical, cast-iron tower (fig. 3 ) to celebrate the passing of the Reform Bill. Of particular interest in light of the present discussion was Trevithick’s plan to raise visitors to the summit on a piston, driven upward within the structure’s hollow central tube by compressed air. It probably is fortunate for Trevithick’s reputation that his plan died shortly after this and the project was forgotten.One project of genuine promise was a tower proposed by the eminent American engineering firm of Clarke, Reeves & Company to be erected at the Centennial Exhibition at Philadelphia in 1876. At the time, this firm was perhaps the leading designer and erector of iron structures in the United States, having executed such works as the Girard Avenue Bridge over the Schuylkill at Fairmount Park, and most of New York’s early elevated railway system. The company’s proposal (fig. 4 - eBook - ePub

- Keyan G Tomaselli, David Scott, Keyan G Tomaselli, David Scott(Authors)

- 2018(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

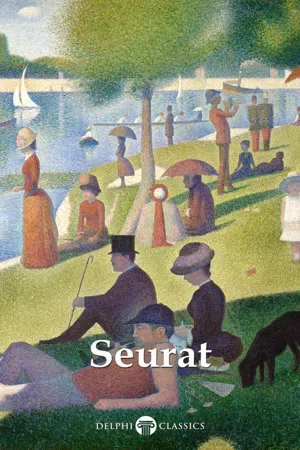

Five years later, however, the Washington Monument, a granite obelisk of 169 meters, exceeded the cathedral in height. 3 In 1884 Jules Bourdais, architect, and Amédée Sébillot, engineer, inspired by the 1,000-foot towers, proposed to build a 300-meter granite tower that was to serve as a monumental lighthouse illuminating Paris. This project would compete against Eiffel’s and the other 105 plans submitted to the 300-meter tower competition opened in 1886 by Edouard Lockroy, Ministre du commerce and Commissaire général of the forthcoming Universal Exposition (Lemoine 1989b: 22–23, 33–35). 4 Thus the idea for a 300-meter tower was in the air. In 1884, anticipating the Universal Exposition and the centennial of the French Revolution, two of Eiffel’s engineers, Maurice Koechlin and Emile Nouguier, drew up the plan for a commemorative tower, whose form was derived from that of the pylons used to support the viaducts and bridges produced by Eiffel’s company, primarily those of the Garabit Viaduct (1879–1884) on which Koechlin had worked since his entry into the company in 1879 (Lemoine 1989a: 57, 86). These pylons were in themselves supreme engineering feats, the result of meticulous calculations that increased their sturdiness and resistance to wind, designed and perfected by Eiffel and his engineers. The same structure, designed by Koechlin, had been used for the internal support of the Statue of Liberty (Lemoine 1989a: 74). Bereft of its functional status, the pylon that became the Eiffel Tower highlights the particular form and design that characterized Eiffel’s many engineering projects. Its simple skeleton was dressed up by architect Stephen Sauvestre, who added decorative arches below the first and second platforms, a glass arcade on the first platform, statues of trumpeting angels on the second, and an immense glass bulb at the top (Lemoine 1989b: 26–29). Though simplified in its final form, this plan won Eiffel’s support - Peter Russell, Delphi Classics(Authors)

- 2019(Publication Date)

- Delphi Classics Ltd(Publisher)

The Eiffel Tower

Seurat’s enduring interest in the vertical was chiefly influenced by the teachings of Humbert de Superville, who advocated that the state of a body placed perpendicular to the horizon expresses the posture of man standing erect, turned toward the sky in a commanding position. In Seurat’s artworks, the figures appear as incredibly straight forms, standing erect like tall monuments, not mere living beings. Whereas many painters placed primary importance on levels and horizontality, for Seurat his interest was for forms of verticality. Factory chimneys, telegraph poles, scaffolding frames and trombone players commanded much more authority in his paintings than do the flat views of streets, villages, land and sea. All forms that are expressed perpendicular to the plane of the horizon offer infinite amusement to this painter of scientific theories. The vertical line, it would seem, constitutes the order of every other element in the composition, serving as an aspiring shoot, enhancing all others features by defining their relationship to the inclination of the dominant form. In no other canvas is Seurat’s fascination with the vertical more apparent than in his 1889 depiction of the Eiffel Tower.The wrought-iron lattice tower, located on the Champ de Mars, was named after the engineer Gustave Eiffel, whose company designed and built it. Constructed from 1887 to 1889 as the entrance to the 1889 World’s Fair, it was initially criticised by many of France’s leading artists and intellectuals for its design, though of course today it represents a global cultural icon of France. It is remains one of the world’s most recognisable structures, measuring 324 metres, composed of 12,000 metal parts held in place by 2,500,000 rivets. It is the most visited paid monument, according to recent findings. During its construction, the Tower surpassed the Washington Monument, making it the tallest man-made structure in the world. It held this record for 41 years until the Chrysler Building in New York City was finished in 1930. When viewing Seurat’s grand portrayal of the Eiffel Tower, produced soon after its completion, it is immediately clear that he was not among its initial detractors.- eBook - ePub

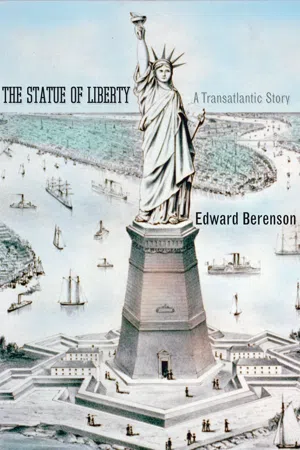

The Statue of Liberty

A Transatlantic Story

- Edward Berenson(Author)

- 2012(Publication Date)

- Yale University Press(Publisher)

In reality, the visible statue is but a wafer of oxidized copper hammered to a breadth of just 3/32 of an inch—slightly thicker than a penny. It could never stand on its own. Instead, it hangs—all 151 feet of it—on an elegant, invisible skeleton of iron conceived by Gustave Eiffel. In a sense, the Statue of Liberty is a modernist Eiffel Tower sheathed in the respectable garb of classical antiquity. It is analogous to the great nineteenth-century train stations whose core structures were shaped from iron and glass but then discreetly hidden behind conventional facades of stone. Urban planners believed the new stations would be too shocking if they weren’t made to blend in. The Eiffel Tower, built for the 1889 International Exposition, explicitly broke with this model by uncloaking the Statue of Liberty’s wrought-iron skeleton for all the world to see. Eiffel’s modern pyramid would stand as a pure display of engineering genius that served no purpose other than to reveal a new form of art—though even he added some unnecessary architectural adornments. 2 It’s worth noting that although Liberty’s skeleton is invisible from the outside, visitors can see it when they venture inside. A narrow spiral staircase winds around the skeleton’s central pylon all the way to the interior of the head. From that vantage point visitors can look out on the harbor through a windowed dome; en route they can admire the extraordinary metal armature that holds the statue up. 3 In the 1860s and ’70s Eiffel had made himself perhaps the world’s greatest builder of railway bridges. Most notable are those that span the Douro River in Oporto, Portugal, and the Truyère in Garabit, France. In both, Eiffel pioneered the use of extraordinarily long iron girders, sweeping arches with no center beams, and flexible joints designed to absorb heat and cold and the shock of moving trains - Ian Aitken, Ian Aitken(Authors)

- 2013(Publication Date)

- Routledge(Publisher)

EDOI: 10.4324/9780203148068-6Eiffel Tower, The

(France, Clair, 1928)René Clair’s short film La Tour (The Eiffel Tower), with a running time of fifteen minutes, is a paean to the French icon of modernity—the Eiffel Tower. The film is constructed as a cinematic postcard using rhythmical montage and editing as its poetic means of expression. Similar to the ‘city symphonies’, many of which were being made at the same time, Clair’s film straddles the margins between documentary and experimental film in its treatment of subject matter. Traveling up and down the monument, Clair’s camera emphasizes the ‘iron lass’ itself and the materials used to create it: the iron girders, the elevators, the cages. Clair constructs his film with sequences of varying lengths and speed, which make up a visual poem. As a hybrid genre it represents, as do many of Clair’s short films, an attempt at ‘pure cinema’, a film that is totally free of narrative restraints, and whose subject is realized completely through the creative use of the film medium.The Eiffel Tower was made after René Clair had completed Une Chapeau de paille d’Italie/The Italian Straw Hat in 1927. Clair had used the French landmark as an important setting in his film, Paris qui dort (1924), and felt that he had not used it enough because of the requirements of the scenario. The director wanted to make a film (‘une documentaire lyrique’) expressing his adoration of the Eiffel Tower. He discussed the idea with his production company, Albatros-Kamenka, which in turn provided him with a camera and film for the project. The short film was shot on location at the Eiffel Tower during the spring of 1928, and editing was completed in the autumn of that year.The Eiffel Tower begins with a postcard-like image of the tower standing against a cloud-filled sky. This pictorial stasis is soon broken by a rapid montage of images of portions of the tower. Clair then returns to the opening shot and fades out. The director then uses a series of short sequences, interconnected by dissolves, showing the history of the construction of the monument. Beginning with a portrait of Gustave Eiffel and architectural blueprints, the sequence progresses through the birth of the tower. The final shot of this sequence shows the completed tower with a title card that reads ‘1889’. Clair then uses a slow tilt all the way up the tower that fades to black. The camera then enters the structure and begins an upward ascent to the various observation decks. Clair’s camera movements progress upward from shot to shot, either by tilting the camera or with ‘crane shots’ taken from the tower elevator. At each level Clair pauses the camera to inspect the surroundings before progressing to another upward tilt to the next platform. When Clair’s camera reaches the top, it briefly looks down to observe a man below looking down on the crowd below him. The camera then begins to descend much more quickly until it reaches ground level. Clair then returns to a close shot of the top of the tower. The end of the film returns to its opening postcard-like image of the Eiffel Tower amid a cloud-filled skyline.