![]()

CHAPTER

1

Positive Leadership

As of this writing, more than 70,000 books on leadership are currently in print. Why would anyone want to produce one more? It is because the vast majority of these leadership books are based on the prescriptions of celebrated leaders recounting their own experiences, convenience samples of people’s opinions, or storytellers’ recitations of inspirational examples. This book is different. It relies wholly on strategies that have been validated by empirical research. It explains the practical approaches to leadership that have emerged from social science research. Because these strategies are not commonly practiced, this book provides some unusual but pragmatic strategies for leaders who want to markedly improve their effectiveness.

This book introduces the concept of positive leadership, or the ways in which leaders enable positively deviant performance, foster an affirmative orientation in organizations, and engender a focus on virtuousness and the best of the human condition. Positive leadership applies positive principles arising from the newly emerging fields of positive organizational scholarship (Cameron, Dutton, & Quinn, 2003; Cameron & Spreitzer, 2012), positive psychology (Seligman, 1999), and positive change (Cooperrider & Sriv-astva, 1987). It helps answer the question “So what can I do if I want to become a more positive leader?”

Positive leadership emphasizes what elevates individuals and organizations (in addition to what challenges them), what goes right in organizations (in addition to what goes wrong), what is life-giving (in addition to what is problematic or life-depleting), what is experienced as good (in addition to what is objectionable), what is extraordinary (in addition to what is merely effective), and what is inspiring (in addition to what is difficult or arduous). It promotes outcomes such as thriving at work, interpersonal flourishing, virtuous behaviors, positive emotions, and energizing networks. In this book the focus is primarily on the role of positive leaders in enabling positively deviant performance.

To be more specific, positive leadership emphasizes three different orientations:

(1) It stresses the facilitation of positively deviant performance, or an emphasis on outcomes that dramatically exceed common or expected performance. Facilitating positive deviance is not the same as achieving ordinary success (such as profitability or effectiveness); rather, positive deviance represents “intentional behaviors that depart from the norm of a reference group in honorable ways” (Spreitzer & Sonenshein, 2003: 209). Positive leadership aims to help individuals and organizations attain spectacular levels of achievement.

(2) It emphasizes an affirmative bias, or a focus on strengths and capabilities and on affirming human potential (Buckingham & Clifton, 2001). Its orientation is toward enabling thriving and flourishing at least as much as addressing obstacles and impediments. Without being Pollyannaish, it stresses positive communication, optimism, and strengths, as well as the value and opportunity embedded in problems and weaknesses.

Positive leadership does not ignore negative events and, in fact, acknowledges the importance of the negative in producing extraordinary outcomes. Difficulties and adverse occurrences often stimulate positive outcomes that would never occur otherwise. Being a positive leader is not the same as merely being nice, charismatic, trustworthy, or a servant leader (Conger, 1989; Greenleaf, 1977). Rather, it incorporates these attributes and supplements them with a focus on strategies that provide strengths-based, positive energy to individuals and organizations.

(3) The third connotation emphasizes facilitating the best of the human condition, or a focus on virtuousness (Cameron & Caza, 2004; Spreitzer & Sonenshein, 2003). Positive leadership is based on a eudaemonistic assumption; that is, an inclination exists in all human systems toward goodness for its intrinsic value (Aristotle, Metaphysics XII; Dutton & Sonenshein, 2007). Whereas there has been some debate regarding what constitutes goodness and whether universal human virtues can be identified, all societies and cultures possess catalogs of traits they deem virtuous (Dent, 1984; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Positive leadership is oriented toward developing what Aristotle labeled goods of first intent, or to “that which is good in itself and is to be chosen for its own sake” (Aristotle, Metaphysics XII: 3). An orientation exists, in other words, toward fostering virtuousness in individuals and organizations.

CRITICISMS AND CONCERNS

To be fair, some are very skeptical of an emphasis on positive leadership. They claim that a focus on the positive is “saccharine and Pollyannaish,” “ethnocentric and representing a Western bias,” “ignorant of negative phenomena,” “elitist,” “mitigates against hard work and invites unpre-paredness,” “leads to reckless optimism,” “represents a narrow moral agenda,” and even “produces delusional thinking” (see Ehrenreich, 2009; Fineman, 2006; George, 2004; Hackman, 2008). They imply that it represents a new age opiate in the face of escalating challenges. One author maintains that not only is there little evidence that posi-tivity is beneficial but, in fact, it is harmful to organizations (Ehrenreich, 2009).

This book aims to provide the evidence that the reverse is actually true. Positive leadership makes a positive difference. The positive strategies described here are universal across cultures. Cultural differences may alter the manner in which these strategies are implemented, but evidence suggests that the strategies themselves are universal in their effects. They exemplify a heliotropic effect—or an inclination in all living systems toward positive, life-giving forces. They have practical utility in difficult circumstances as much as in benevolent circumstances.

Far from mitigating against hard work or representing soft, simple, and syrupy actions, these strategies require effort, elevated standards, and genuine competence. The strategies represent pragmatic, validated levers available to leaders so that they can achieve positive performance in organizations and in individuals. The empirical evidence presented in the chapters that follow is offered to support this conclusion.

AN EXAMPLE OF POSITIVE DEVIANCE

An easy way to identify positive leadership is to observe positive deviance. An example of such performance is illustrated by the cleanup and closure of the Rocky Flats Nuclear Weapons Production Facility near Denver, Colorado (Cameron & Lavine, 2006). At the time the facility was rife with conflict and antagonism. It had been raided and temporarily closed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1989 for alleged violations of environmental laws, and employee grievances had skyrocketed. More than 100 tons of radioactive plutonium were on site, and more than 250,000 cubic meters of low-level radioactive waste were being stored in temporary drums on the prairie. Broad public sentiment regarded the facility as a danger to surrounding communities, and demonstrations by multiple groups had been staged there from the 1960s through the 1980s in protest of nuclear proliferation and potential radioactive pollution. In fact, radioactive pollution levels were estimated to be so high that a 1994 ABC Nightline broadcast labeled two buildings on the site the most dangerous buildings in America.

The Department of Energy estimated that closing and cleaning up the facility would require a minimum of 70 years and cost more than $36 billion. A Denver, Colorado, engineering and environmental firm—CH2MHILL—won the contract to clean up and close the 6,000-acre site consisting of 800 buildings.

CH2MHILL completed the assignment 60 years ahead of schedule, $30 billion under budget, and 13 times cleaner than required by federal standards. Antagonists such as citizen action groups, community councils, and state regulators changed from being adversaries and protesters to advocates, lobbyists, and partners. Labor relations among the three unions (i.e., steelworkers, security guards, building trades) improved from 900 grievances to the best in the steelworker president’s work life. A culture of lifelong employment and employee entitlement was replaced by a workforce that enthusiastically worked itself out of a job as quickly as possible. Safety performance exceeded federal standards by twofold and more than 200 technological innovations were produced in the service of faster and safer performance.

These achievements far exceeded every knowledgeable expert’s predictions of performance. They were, in short, a quintessential example of positive deviance achieved by positive leadership. The U.S. Department of Energy attributed positive leadership, in fact, as a key factor in accounting for this dramatic success (see Cameron & Lavine, 2006: 77).

Of course, for positive leaders to focus on positive deviance does not mean that they ignore nonpositive conditions or situations where mistakes, crises, deterioration, or problems are present. Most of the time people and organizations fall short of achieving the best they can be or fail to fulfill their optimal potential. Many positive outcomes are stimulated by trials and difficulties; for example, demonstrated courage, resilience, forgiveness, and compassion are relevant only in the context of negative events. As illustrated by the Rocky Flats example, some of the best of human and organizational attributes are revealed only when confronting obstacles, challenges, or detrimental circumstances. Common human experience, as well as abundant scientific evidence, supports the idea that negativity has a place in human flourishing (Cameron, 2008). Negative news sells more than positive news, people are affected more by negative feedback than positive feedback, and traumatic events have a greater impact on humans than positive events.

A comprehensive review of psychological research by Baumeister, Bratslavsky, Finkenauer, and Vohs (2001: 323) summarized this conclusion by pointing out that “bad is stronger than good.” Human beings, they maintained, react more strongly to negative phenomena than to positive phenomena. They learn early in life to be vigilant in responding to the negative and to ignore natural heliotropic tendencies. Thus achieving positive deviance is not dependent on completely positive conditions, just like languishing and failure are not dependent on constant negative conditions. A role exists for both positive and negative circumstances in producing positive deviance (Bagozzi, 2003), and both conducive and challenging conditions may lead to positive deviance. As everyone knows, “all sunshine makes a desert.”

Moreover, when organizations should fail but do not, when they are supposed to wither but bounce back, when they ought to become rigid but remain flexible and agile, they also demonstrate a form of positive deviance (Weick, 2003). The cleanup and closure of Rocky Flats was expected to fail; nuclear aircraft carriers in the 1990 Persian Gulf War were not supposed to produce perfect performance (Weick & Roberts, 1993); and the U.S. Olympic hockey team in 1980 was predicted to be annihilated by the Russians. Nonfailure in these circumstances also represents positive deviance.

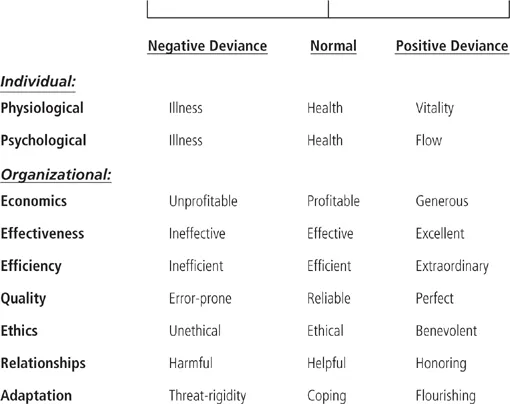

One way to think about positive deviance is illustrated by a continuum shown in Figure 1.1. The continuum depicts a state of normal or expected performance in the middle, a condition of negatively deviant performance on the left, and a state of positively deviant performance on the right. Negative deviance and positive deviance depict aberrations from normal functioning, problematic on one end and virtuous on the other end.

FIGURE 1.1 A Deviance Continuum

(SOURCE: Cameron, 2003)

The figure shows a condition of physiological and psychological illness on the left and healthy functioning in the middle (i.e., the absence of illness). On the right side is positive deviance, which may be illustrated by high levels of physical vitality (e.g., Olympic fitness levels) or psychological flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990; Fredrickson, 2001). At the organizational level, the figure portrays conditions ranging from ineffective, inefficient, and error-prone performance on the left side to effective, efficient, and reliable performance in the middle. On the right side is extraordinarily positive, virtuous, or extraordinary organizational performance. The extreme right and left points on the continuum are qualitatively distinct from the center point. They do not merely represent a greater or lesser quantity of the middle attributes.

For the most part, organizations are designed to foster stability, steadiness, and predictability (March & Simon, 1958; Parsons, 1951; Weber, 1992)—that is, to remain in the middle of the Figure 1.1 continuum. Investors tend to flee from companies that are deviant or unpredictable in their performance (Marcus, 2005). Consequently, organizations formaliz...