![]()

Part I

Adaptive

The business environment has changed markedly over the past 30 years. Driven by a host of powerful forces—including digitization, connectivity, trade liberalization, global competition, and consumer activism—today's competitive terrain is more unsettled and less predictable than ever before. And the breadth of new conditions that companies face continues to grow. The effects on corporate performance have been dramatic. Turbulence within industries, measured by such metrics as volatility in revenue growth, revenue ranking, and operating margins, is demonstrably greater and more prevalent than ever. Industry leadership, once relatively stable, now changes rapidly.

To succeed, businesses must rethink how they generate competitive advantage. A critical element of this is understanding the competitive environment (or environments) in which the company operates—and choosing an appropriate style of strategy for that environment. Is the environment one that the company has the potential to shape, for example, or is it one over which the company has minimal influence? The two scenarios bear little resemblance and thus call for wholly different styles of strategy.

A second must-have for success is the ability to adapt to unpredictable and changing circumstances. Companies that can adjust and learn better, faster, and more economically than their rivals stand to gain a decisive advantage in the marketplace. Indeed, what we term adaptive advantage increasingly trumps classical, static sources of competitive advantage, such as scale and position.

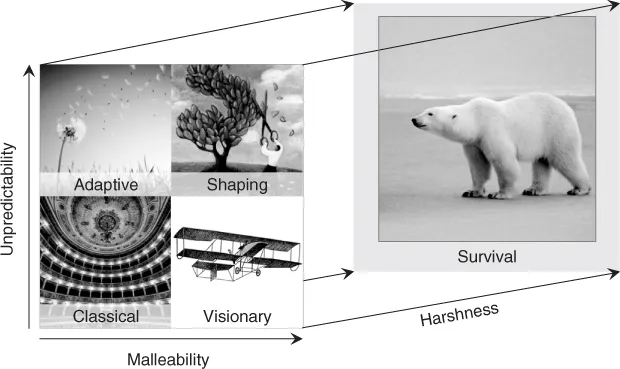

The chapters featured here delve into these topics. Chapter 1, “Why Strategy Needs a Strategy,” introduces the concept of strategic styles and explains how they should be deployed. We identify five distinct styles of strategy—classical, shaping, visionary, survival, and adaptive—and assert that executives will increasingly need to learn and manage a portfolio of different ones.

We believe that five capabilities are needed to be adaptive: the ability to read and act on signals of change; the ability to experiment rapidly, frequently, and economically; the ability to manage complex, multicompany systems; the ability to mobilize the organization; and the ability to generate value and achieve competitive advantage by sustainably aligning the company's business model with its broader social and ecological context. Chapter 2, “Adaptability: The New Competitive Advantage,” discusses the first four of these and offers tips for large corporations seeking to become more adaptive. We discuss the fifth source of advantage in Chapter 34, “Social Advantage,” which appears in Section 8 of this book.

Chapter 3, “Systems Advantage,” focuses on a special case of adaptive advantage—gaining advantage through multiparty ecosystems. The article explains the rationale for such an approach and discusses principles for designing and managing advantaged and adaptive systems. Chapter 4, “Adaptive Leadership,” argues that just as today's environment demands a different approach to strategy, it also calls for a different type of business leader. Increasingly, today's successful leaders eschew traditional command-and-control tactics. Rather, they focus on creating the conditions that enable dynamic networks of actors to achieve common goals against a backdrop of uncertainty.

Adaptability is an ability to develop new capabilities, but it wasn't always obvious that capabilities matter. In fact, when Harvard Business Review published our article “Competing on Capabilities” in 1992, the notion that capabilities are a critical source of strategic advantage was a novel one. At that time, managers were more focused on factors such as scale, position, and operational efficiency. Although those factors were and still are important, we argued that competition was a “war of movement” in which companies had to move quickly in and out of products, markets, and even entire businesses. We stand by that view. Today, the piece (a condensed version of which is published here in Chapter 5) is one of BCG's most well-read articles—and has redefined how executives think about competitive advantage.

![]()

Chapter 1

Why Strategy Needs a Strategy

Martin Reeves, Michael Deimler, Claire Love, and Philipp Tillmanns

Abridged and reprinted with permission. Copyright © 2012 by Harvard Business Publishing; all rights reserved.

The oil industry holds relatively few surprises for strategists. Things change, of course, sometimes dramatically, but in relatively predictable ways. Planners know, for instance, that global supply will rise and fall as geopolitical forces play out and new resources are discovered and exploited. They know that demand will rise and fall with gross domestic products (GDPs), weather conditions, and the like. Because these factors are outside companies' control, no one is really in a position to change the game much. A company carefully marshals its unique capabilities and resources to stake out and defend its competitive position in this fairly stable firmament.

The Internet software industry would be a nightmare for an oil industry strategist. Innovations and new companies pop up frequently, seemingly out of nowhere, and the pace at which companies can build—or lose—volume and market share is head-spinning. A player like Google or Facebook can, without much warning, introduce a new platform that fundamentally alters the basis of competition. In this environment, competitive advantage comes from reading and responding to signals faster than your rivals do, adapting quickly to change, or capitalizing on technological leadership to influence how demand and competition evolve.

Clearly, the kinds of strategies that would work in the oil industry have practically no hope of working in the far less predictable and far less settled arena of Internet software. And the skill sets that oil and software strategists need are worlds apart as well. Companies operating in such dissimilar competitive environments should be planning, developing, and deploying their strategies in markedly different ways. But all too often they are not.

What's stopping executives from making strategy in a way that fits their situation? We believe they lack a systematic way to go about it—a strategy for making strategy. Here we present a simple framework that divides strategy planning into four styles according to how predictable your environment is and how much power you have to change it. Using this framework, corporate leaders can match their strategic style to the particular conditions of their industry or geographic market.

Finding the Right Strategic Style

Strategy usually begins with an assessment of your industry. Your choice of strategic style should begin there as well. Although many industry factors will play into the strategy you actually formulate, you can narrow down your options by considering just two critical factors: predictability (how far into the future and how accurately can you confidently forecast demand, corporate performance, competitive dynamics, and market expectations?) and malleability (to what extent can you or your competitors influence those factors?).

Put these two variables into a matrix, and four broad strategic styles—which we label classical, adaptive, shaping, and visionary—emerge (Figure 1.1). Each style is associated with distinct planning practices and is best suited to one environment.

Let's look at each style in turn.

Classical

When you operate in an industry whose environment is predictable but hard for your company to change, a classical strategic style has the best chance of success. This is the style familiar to most managers and business school graduates—five forces, blue ocean, and growth-share matrix analyses are all manifestations of it. A company sets a goal, targeting the most favorable market position it can attain by capitalizing on its particular capabilities and resources, and then tries to build and fortify that position through orderly, successive rounds of planning, using quantitative predictive methods that allow it to project well into the future. Once such plans are set, they tend to stay in place for several years. Classical strategic planning can work well as a stand-alone function because it requires special analytic and quantitative skills, and things move slowly enough to allow for information to pass between departments.

Oil company strategists, like those in many other mature industries, effectively employ the classical style. At a major oil company such as ExxonMobil or Shell, for instance, highly trained analysts in the corporate strategic planning office spend their days developing detailed perspectives on the long-term economic factors relating to demand and the technological factors relating to supply. These analyses allow them to devise upstream oil extraction plans that may stretch 10 years into the future and downstream production capacity plans up to 5 years out. These plans, in turn, inform multiyear financial forecasts, which determine annual targets that are focused on honing the efficiencies required to maintain and bolster the company's market position and performance. Only in the face of something extraordinary—an extended Gulf war, for instance, or a series of major oil refinery shutdowns—would plans be seriously revisited more frequently than once a year.

Adaptive

The classical approach works for oil companies because their strategists operate in an environment in which the most attractive positions and the most rewarded capabilities today will, in all likelihood, remain the same tomorrow. But that has never been true for some industries, and it's becoming less and less true where global competition, technological innovation, social feedback loops, and economic uncertainty combine to make the environment radically and persistently unpredictable. In such an environment, a carefully crafted classical strategy may become obsolete within months or even weeks.

Companies in this situation need a more adaptive approach, whereby they can constantly refine goals and tactics and shift, acquire, or divest resources smoothly and promptly. In such a fast-moving, reactive environment, when predictions are likely to be wrong and long-term plans are essentially useless, the goal cannot be to optimize efficiency; rather, it must be to engineer flexibility. Accordingly, planning cycles may shrink to less than a year or even become continual. Plans take the form not of carefully specified blueprints but of rough hypotheses based on the best available data. In testing out those hypotheses, strategy must be tightly linked with or embedded in operations to best capture change signals and minimize information loss and time lags.

Specialty fashion retailing is a good example of this. Tastes change quickly. Brands become hot (or not) overnight. The Spanish retailer Zara uses the adaptive approach. Zara does not rely heavily on a formal planning process; rather, its strategic style is baked into its flexible supply chain. Zara need not predict or make bets on which fashions will capture its customers' imaginations and wallets from month to month; instead, it can respond quickly to information from its retail stores, constantly experiment with various offerings, and smoothly adjust to events as they play out.

Shaping

Exxon's strategists and Zara's designers have one critical thing in common: they take their competitive environment as a given. Some environments, as Internet software vendors well know, can't be taken as a given. For instance, in young high-growth industries where barriers to entry are low, innovation rates are high, demand is very hard to predict, and the relative positions of competitors are in flux, a company can often radically shift the course of industry development through some innovative move. A mature industry that's similarly fragmented and not dominated by a few powerful incumbents, or is stagnant and ripe for disruption, is also likely to be similarly malleable.

In such an environment, a company employing a classical or even an adaptive strategy to find the best possible market position runs the risk of selling itself short and missing opportunities to control its own fate. It would do better to employ a strategy in which the goal is to shape the unpredictable environment to its own advantage before someone else does—so that it benefits no matter how things play out.

Like an adaptive strategy, a shaping strategy embraces short or continual planning cycles. Flexibility is paramount, little reliance is placed on elaborate prediction mechanisms, and the strategy is most commonly implemented as a portfolio of experiments. But unlike adapters, shapers focus beyond the boundaries of their own company, often by rallying a formidable ecosystem of customers, suppliers, and/or complementors to their cause by defining attractive new markets, standards, technology platforms, and business practices.

That's essentially how Facebook overtook the incumbent MySpace in just a few years. One of Facebook's savviest strategic moves was to open its social networking platform to outside developers in 2007, thus attracting all manner of applications to its site. By 2008 it had attracted 33,000 applications; by 2010 that number had risen to more than 550,000. So as the industry developed and more than two-thirds of the successful social networking apps turned out to be games, it was not surprising that the most popular ones—created by Zynga, Playdom, and Playfish—were operating from, and enriching, Facebook's site.

Visionary

Sometimes, not only does a company have the power to shape the future, but it's possible to know that future and to predict the path to realizing it. Those times call for bold strategies—the kind entrepreneurs use to create entirely new markets (as Edison did for electricity and Martine Rothblatt did for XM satellite radio) or corporate leaders use to revitalize a company with a wholly new vision (as Ratan Tata is trying to do with the ultra-affordable Tata Nano automobile). These are the big bets, the build-it-and-they-will-come strategies.

Like a shaping strategist, the visionary considers the environment not as a given but as something that can be molded to advantage. Even so, the visionary style has more in common w...