![]()

Chapter 1

What is Project Financing?

Project financing can be arranged when a particular facility or a related set of assets is capable of functioning profitably as an independent economic unit. The sponsor(s) of such a unit may find it advantageous to form a new legal entity to construct, own, and operate the project. If sufficient profit is predicted, the project company can finance construction of the project on a project basis, which involves the issuance of equity securities (generally to the sponsors of the project) and of debt securities that are designed to be self-liquidating from the revenues derived from project operations.

Although project financings have certain common features, financing on a project basis necessarily involves tailoring the financing package to the circumstances of a particular project. Expert financial engineering is often just as critical to the success of a large project as are the traditional forms of engineering.

Project financing is a well-established financing technique. Thomson Financial's Project Finance International database lists 4,360 projects that have been undertaken since 2002. About 10 percent of these are large projects costing $1 billion or more. Looking forward, the United States and many other countries face enormous infrastructure financing requirements. Project financing is a technique that could be applied to many of these projects.

What is Project Financing?

Project financing may be defined as the raising of funds on a limited-recourse or nonrecourse basis to finance an economically separable capital investment project in which the providers of the funds look primarily to the cash flow from the project as the source of funds to service their loans and provide the return of and a return on their equity invested in the project.1 The terms of the debt and equity securities are tailored to the cash flow characteristics of the project. For their security, the project debt securities depend mainly on the profitability of the project and on the collateral value of the project's assets. Assets that have been financed on a project basis include pipelines, refineries, electric generating facilities, hydroelectric projects, dock facilities, mines, toll roads, and mineral processing facilities.

Project financings typically include the following basic features:

1. An agreement by financially responsible parties to complete the project and, toward that end, to make available to the project the funds necessary to achieve completion.

2. An agreement by financially responsible parties (typically taking the form of a contract for the purchase of project output) that, when project completion occurs and operations commence, the project will generate sufficient cash flow to enable it to meet all its operating expenses and debt service requirements under all reasonably foreseeable circumstances.

3. Assurances by financially responsible parties that, in the event a disruption in operation occurs and funds are required to restore the project to operating condition, the necessary funds will be made available through insurance recoveries, advances against future deliveries, or some other means.

Project financing should be distinguished from conventional direct financing, or what may be termed financing on a firm's general credit. In connection with a conventional direct financing, lenders to the firm look to the firm's entire asset portfolio to generate the cash flow to service their loans. The assets and their financing are integrated into the firm's asset and liability portfolios. Often, such loans are not secured by any pledge of collateral. The critical distinguishing feature of a project financing is that the project is a distinct legal entity; project assets, project-related contracts, and project cash flow are segregated to a substantial degree from the sponsoring entity. The financing structure is designed to allocate financial returns and risks more efficiently than a conventional financing structure. In a project financing, the sponsors provide, at most, limited recourse to cash flows from their other assets that are not part of the project. Also, they typically pledge the project assets, but none of their other assets, to secure the project loans.

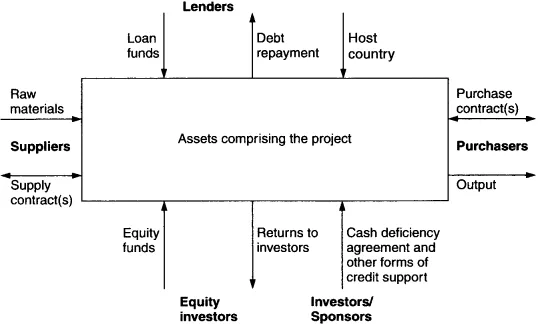

The term project financing is widely misused and perhaps even more widely misunderstood. To clarify the definition, it is important to appreciate what the term does not mean. Project financing is not a means of raising funds to finance a project that is so weak economically that it may not be able to service its debt or provide an acceptable rate of return to equity investors. In other words, it is not a means of financing a project that cannot be financed on a conventional basis. A project financing requires careful financial engineering to allocate the risks and rewards among the involved parties in a manner that is mutually acceptable. Figure 1.1 illustrates the basic elements in a capital investment that is financed on a project basis.

At the center is a discrete asset, a separate facility, or a related set of assets that has a specific purpose. Often, this purpose is related to raw materials acquisition, production, processing, or delivery. More recently, this asset is a power-generating station, toll road, or some other item of infrastructure. Many projects involve the modernization or upgrade of an existing facility, or a brownfield project, rather than the construction of a brand new facility, or greenfield project.

As already noted, this facility or group of assets must be capable of standing alone as an independent economic unit. The operations, supported by a variety of contractual arrangements, must be organized so that the project has the unquestioned ability to generate sufficient cash flow to repay its debts.

A project must include all the facilities that are necessary to constitute an economically independent, viable operating entity. For example, a project cannot be an integral part of another facility. If the project will rely on any assets owned by others for any stage in its operating cycle, the project's unconditional access to these facilities must be contractually assured at all times, regardless of events.

Project financing can be beneficial to a company with a proposed project when (1) the project's output would be in such strong demand that purchasers would be willing to enter into long-term purchase contracts and (2) the contracts would have strong enough provisions that banks would be willing to advance funds to finance construction on the basis of the contracts. Project financing can be beneficial to lenders when it reduces the risk of project failure, leads to tighter covenant packages, or facilitates a lower cost of resolving financial distress.

For example, project financing can be advantageous to a developing country when it has a valuable resource deposit, other responsible parties would like to develop the deposit, and the host country lacks the financial resources to proceed with the project on its own.

A Historical Perspective

Project financing is not a new financing technique. Venture-by-venture financing of finite-life projects has a long history; it was, in fact, the rule in commerce until the seventeenth century. For example, in 1299—more than 700 years ago—the English Crown negotiated a loan from the Frescobaldi (a leading Italian merchant bank of that period) to develop the Devon silver mines.2 The loan contract provided that the lender would be entitled to control the operation of the mines for one year. The lender could take as much unrefined ore as it could extract during that year, but it had to pay all costs of operating the mines. There was no provision for interest.3 The English Crown did not provide any guarantees (nor did anyone else) concerning the quantity or quality of silver that could be extracted during that period. Such a loan arrangement was a forebearer of what is known today as a production payment loan.4

Recent Uses of Project Financing

Project financing has long been used to fund large-scale natural resource projects. (Appendix B provides thumbnail sketches of several noteworthy project financings, including a variety of natural resource projects.) One of the more notable of these projects is the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) Project, which was developed between 1969 and 1977. TAPS was a joint venture of eight of the world's largest oil companies. It involved the construction of an 800-mile pipeline, at a cost of $7.7 billion, to transport crude oil and natural gas liquids from the North Slope of Alaska to the port of Valdez in southern Alaska. TAPS involved a greater capital commitment than all the other pipelines previously built in the continental United States combined. Phillips, Groth, and Richards (1979) describe Sohio's experience in arranging financing to cover its share of the capital cost of TAPS.

More recently, in 1988, five major oil and gas companies formed Hibernia Oil Field Partners to develop a major oil field off the coast of Newfoundland. The projected capital cost was originally $4.1 billion. Production of 110,000 barrels of oil per day was initially projected to start in 1995. Production commenced in 1997 and increased to 220,000 barrels per day in 2003. Production is expected to last between 16 and 20 years. The Hibernia Oil Field Project is a good example of public sector–private sector cooperation to finance a large project. (Public–private partnerships are discussed in Chapter 16.)

The Impact of PURPA

Project financing in the United States was given a boost in 1978 with passage of the Public Utility Regulatory Policy Act (PURPA). Under PURPA, local electric utility companies are required to purchase all the electric output of qualified independent power producers under long-term contracts. The purchase price for the electricity must equal the electric utility's “avoided cost”—that is, its marginal cost—of generating electricity. This provision of PURPA established a foundation for long-term contractual obligations sufficiently strong to support nonrecourse project financing to fund construction costs. The growth of the independent power industry in the United States can be attributed directly to passage of PURPA. For example, roughly half of all power production that came into commercial operation during 1990 came from projects developed under the PURPA regulations.

Innovations in Project Financing

Project financing for manufacturing facilities is another area in which project financing has recently begun to develop. In 1988, General Electric Capital Corporation (GECC) announced that it would expand its project finance group to specialize in financing the construction and operation of industrial facilities. It initiated this effort by providing $105 million of limited-recourse project financing for Bev-Pak Inc. to build a beverage container plant in Monticello, Indiana.5 The plant was owned independently; no beverage producers held ownership stakes. Upon completion, the plant had two state-of-the-art production lines with a combined capacity of 3,200 steel beverage cans per minute. A third production line, added in October 1989, expanded Bev-Pak's capacity to 2 billion cans per year. This output represented about 40 percent of the total steel beverage can output in the United States. Bev-Pak arranged contracts with Coca-Cola and PepsiCo to supply as much as 20 percent of their can requirements. It also arranged a contract with Miller Brewing Company. Bev-Pak enjoyed a competitive advantage: Its state-of-the-art automation enabled it to sell its tin-plated steel cans at a lower price than aluminum cans.6 Moreover, to reduce its economic risk, Bev-Pak retained the flexibility to switch to aluminum can production if the price of aluminum cans were to drop.

Financing a large, highly automated plant involves uncertainty about whether the plant will be able to operate at full capacity. Independent ownership enables the plant to enter into arm's-length agreements to supply competing beverage makers. It thus diversifies its operating risk; it is not dependent on any single brand's success. Moreover, because of economies of scale, entering into a long-term purchase agreement for a portion of the output from a large-scale plant is more cost effective than building a smaller plant in house. Finally, long-term contracts with creditworthy entities furnish the credit strength that supports project financing.

Infrastructure is another area ripe for innovation. Chapter 16 discusses the formation of public–private partnerships to finance generating stations, transportation facilities, and other infrastructure projects. Governments and multilateral agencies have recognized the need to attract private financing for such projects (see Chrisney, 1995; Ferreira, 1995). Chapter 18 describes how private financing was arranged for two toll roads in Mexico. In the past, projects of this type have been financed by the public sector.

Requirements for Project Financing

A project has no operating history at the time of the initial debt financing. Consequently, its creditworthiness depends on the project's anticipated profitability and on the indirect credit support provided by third parties through various contractual arrangements. As a result, lenders require assurances that (1) the project will be placed into service, and (2) once operations begin, the project will constitute an economically viable undertaking. The availability of funds to a project will depend on the sponsor's ability to convince providers of funds that the project is technically feasible and economically viable.

Technical Feasibility

Lenders must be satisfied that the technological processes to be used in the project are feasible for commercial application on the scale contemplated. In brief, providers of funds need assurance that the project will generate output at its design capacity. The technical feasibility of conventional facilities, such as pipelines and electric power generating plants, is generally accepted. But technical feasibility has been a significant concern in such projects as Arctic pipelines, large-scale natural gas liquefaction and transportation facilities, and coal gasification plants. Lenders generally require verifying opinions from independent engineering consultants, particularly if the project will involve unproven technology, unusual environmental conditions, or very large scale.

Economic Viability

The ability of a project to operate successfully and generate adequate cash flow is of paramo...