![]()

1

Diagnosis and Differential Diagnosis of Dementia

Richard Camicioli

Department of Medicine (Neurology), University of Alberta, Canada

Introduction

The burden of dementia, a substantial public health concern, is felt in all societies. After defining dementia, in the following chapter we discuss the diagnosis and differential diagnosis. We outline an approach to the general diagnostic work-up in this chapter, with detailed recommendations for specific situations (e.g. rapid progression, young onset, prominent depression, question of normal pressure hydrocephalus) in the chapters to follow.

Definitions

Dementia is a syndrome in which multiple-domain cognitive impairment, generally including memory impairment, is sufficiently severe to significantly affect everyday function. Memory and one additional area of cognitive impairment, including aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, and executive dysfunction, are required to be affected according to common criteria (DSM-IV). There are other generic dementia criteria, including the ICD-10 criteria,which require that several domains are affected, and newer dementia criteria are being developed (i.e. DSM-V) (Table 1.1). Some criteria have not required memory impairment as a necessary condition for dementia, since it might not be prominently impaired in non-Alzheimer’s dementias, and even occasional patients with Alzheimer’s disease can exceptionally have relatively preserved memory.

There are specific criteria for patients with cerebrovascular disease (vascular cognitive impairment/ vascular dementia) and Parkinson’s disease (Parkinson’s disease dementia - PDD), both of which have a high risk of dementia. Recently, new criteria for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have been proposed to take into account developments in biomarkers and recognition of a prodomal state, termed mild cognitive impairment, which often leads to dementia. Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) shares pathologies of Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Frontotemporal dementia also has distinct features and varied pathology, and typically presents with prominent behavioral features (behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia) or language impairment (non-fluent/agrammatic/logopenic primary progressive aphasia or semantic dementia). Some patients, particularly those with logopenic progressive aphasia, actually have Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Some frontotemporal dementia patients develop co-existent motor neuron disease. Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP), corticobasal ganglionic degeneration (CBGD), and Huntington’s disease are other neurodegenerative disorders that usually have obvious and prominent motor features; patients with these conditions often have cognitive and behavioral problems and develop dementia. Thus, while diagnostic criteria for the dementias are in evolution, making a diagnosis and identifying the specific etiology remain critical in the clinical setting.

Distinct pathologies can be successfully identified by current clinical criteria, albeit with a rate of misdiagnosis. The recognition of unusual presentations, atypical onset, and the prodromal phase of dementias may be assisted by biomarkers (which may differ in these settings). Clinicians must nevertheless recognize these possibilities. Also, it is important to keep in mind that overlapping pathology often occurs in older patients with cognitive impairment or dementia, which might influence the clinical picture.

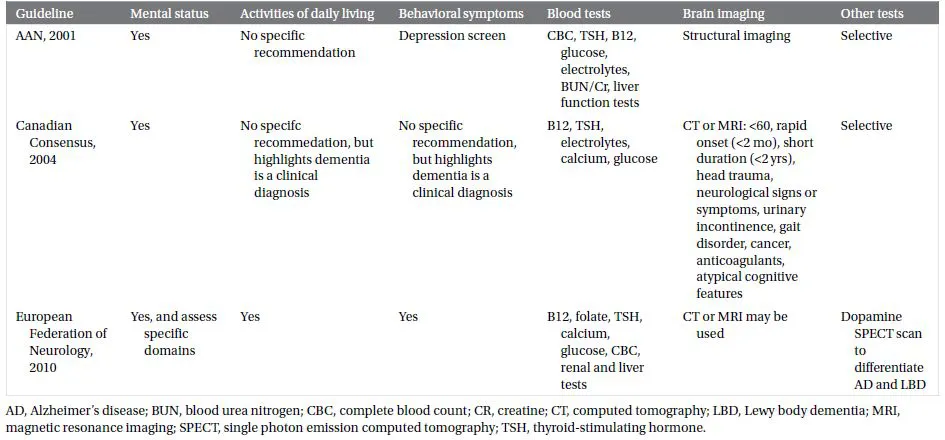

Table 1.1 Comparison of key guidelines for the assessment of dementia

Other chapters consider young-onset and rapidly progressive dementia. Here we consider dementia in people 65 years of age and older.

The clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s diease is confirmed at brain autopsy in 90% of patients. The clinical diagnosis of vascular dementia, Lewy body dementia, and frontotemporal dementia predicts the brain autopsy diagnosis, but not as well as a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s.

Epidemiology

In 2010, dementia was estimated to affect 35.7 million people world-wide. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common dementia in people older than age 65 years, yet Alzheimer’s disease pathology is often accompanied by vascular disease or Lewy bodies. The latter two types of dementia can also occur in “pure” form. The diagnosis of dementia increases mortality risk, regardless of age or etiology of dementia. It is important to recognize that dementia may lead to a debilitated state and death in order to direct interventions appropriately, including palliative approaches. Prediction of death can be challenging in patients with dementia, which may make initiation of formal palliative care services difficult. (Chapter 9 provides a detailed discussion of the role of palliative care in dementia.)

Assessment

History

Obtaining an accurate medical history is central to the diagnosis of dementia. This should identify and qualify the nature of the symptoms as well as their onset and progression. A critical challenge to obtaining an accurate history is that patients themselves may not be able to self-monitor because of their cognitive problems, so obtaining a collateral history is necessary. Memory impairment is a central feature of many dementias and can be expected to interfere with recall of key historical events. In addition, lack of insight can occur in dementia and interfere with the acknowledgment of symptoms. It is important to interview the informant and patient separately at some point in the diagnostic process. While some standardized questionnaires are useful in identifying complaints, these do not replace a thorough history, which remains the gold standard. Instruments that can complement the clinical history include the AD8 dementia screening questionnaire, the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE), the Deterioration Cognitive Observation Scale (DECO), and the Alzheimer Questionnaire (AQ). The General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCog) includes both a cognitive screen and questions regarding cognitive changes and activities of daily living based on caregiver report, which improves sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of dementia.

While the initial focus of the history should be on cognitive complaints and their functional implications, which allow for meeting dementia criteria, psychiatric and behavioral changes need to be identified as they are often present in early dementia, and can be prominent in some patients. In many patients referred for cognitive decline, psychiatric issues may predominate and may be the cause of the so-called cognitive decline. Depression should routinely be assessed in patients with cognitive complaints. It is key to screen for depressive symptoms, and scales such as the Geriatric Depression Scale, which has 15- and 30-item versions (www.stanford.edu/~yesavage/GDS.html), and the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Scale, can be helpful in this regard, though the gold standard is a psychiatric evaluation using a standardized interview schedule. The Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia is validated for the dementia population. Depression can be a risk factor for or coincident with the diagnosis of dementia. Moreover, it can occur de novo in the course of dementia. Although they are distinct symptoms, depression and anxiety often co-exist. Other mood symptoms, such as elation or euphoria, also can occur in dementia, but primary psychiatric disorders should be kept in the differential diagnosis if these are prominent.

While not absolute, the nature of cognitive deficits can help in differentiating depression from dementia. Patients with depression have long response latencies whereas typical patients with Alzheimer’s disease respond with normal latencies. Memory impairment in depression is related to retrieval problems, rather than problems with encoding, where cueing does not improve recall. Alzheimer’s patients also have additional cognitive deficits, particularly in visuospatial and language domains, that would not be seen in depression. As noted, depression can co-exist with dementia and it is common in Alzheimer’s disease as well as vascular dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies.

Other neuropsychiatric problems that should be considered include positive symptoms such as disinhibition, irritability, agitation, aggression, or abnormal motor behavior as well as negative symptoms such as apathy. Delusions and hallucinations are also highly relevant. These symptoms can be assessed using standardized instruments such as the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI). They can occur early in the course of dementia and can evolve over time. The Frontal Behavior Inventory can help with the differentiation of Alzheimer’s disease from frontotemporal dementia. Patients with frontotemporal dementia often lack emotional responsiveness and can develop apathy, which can be mistaken for depression but is characterized by lack of motivation. Psychotic features, particularly visual hallucinations, are characteristic of PDD and DLB. Delusions are not as specific but can be equally disturbing to family members.

It is critical to identify functional impairment. By definition, patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) do not have substantial functional impairment, while patients with dementia do. Practically speaking, at the time of diagnostic evaluation, assessment of basic and instrumental activities of daily living is performed by asking the patient and their caregiver how the patient performs everyday tasks. Basic activities of daily living such as getting in and out of bed, dressing, walking, toileting, bathing, and eating are not affected early in the course of dementia. Instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) such as answering the phone, taking pills, handling money, shopping, cooking, and driving are affected early in the course.

Typically a standardized questionnaire is used to address activities of daily living. Examples include the Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ) which addresses IADLs, the Lawton and Brody IADL and Physical Self-Maintenance Scale and the OARS Functional Assessment Questionnaire. Assessment is not as straightforward as it seems, as there is often a mild degree of functional impairment in MCI, where such impairments may predict future cognitive decline. Moreover, a given patient’s living situation might not tax their functional capacity. Conversely, a patient who is working might have some workplace impairment despite relatively well-preserved cognitive assessment. In the setting of a disorder that affects motor function, such as Parkinson’s disease or after a stroke, it can be challenging to determine if a change in a patient’s function is related to cognitive or motor function.

Prescribed and over-the-counter medications, as well as substances of abuse (notably alcohol), are important to identify as they might contribute to cognitive impairment. If the patient is not able to list these accurately, this suggests an important area of functional impairment that requires intervention. All co-morbid medical conditions need to be identified. Vascular risk factors such as smoking, diabetes, obesity, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and non-central nervous system (CNS) vascular disease (cardiac, renal, peripheral) increase the risk for cerebrovascular events, which can contribute to dementia, and can be covert. These are risk factors for dementia in the absence of identifiable stroke as well. Symptoms suggestive of cancer, especially in patients with a rapid course, raise the concern of direct or indirect central nervous system involvement.

A detailed family history is critical. While familial dementia commonly has a young onset, risk of dementia in older people is also increased in the setting of a family history. A third to half of people with frontotemporal dementia have a family history compared to roughly one in 10 patients with Alzheimer’s disease. At a minimum, all first-degree relatives should be identified and the presence of neurological disorders determined. This history should not be restricted to examining dementia risk, since disorders such as Parkinson’s disease and motor neuron disease may be associated with an increased risk of dementia in family members. If the family history is consistent with a hereditary dementia, testing can be offered but this should be done after appropriated counseling. At-risk family members should only be tested after genetic counseling. Huntington’s disease is a relatively common cause of dementia in younger individuals, but can occasionally be identified for the first time in older patients without an obvious family history.

Physical examination

General examination

The general examination might identify specific co-morbid conditions, such as atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). An abdominal or rectal mass, suggesting a neoplasm, might be uncovered. These might directly or indirectly contribute to cognitive dysfunction. Some findings on general examinations, such as postural hypotension, may suggest a specific diagnosis such as dementia with Lewy bodies.

Cognitive evaluation

Cognitive assessment at the bedside is important for both differential diagnosis and rating the severity of cognitive impairment. Cognitive domains to be assessed correspond to those involved in the diagnosis, including attention, orientation, memory, executive function, language, praxis, and visuospatial abilities.

Several standardized assessment instruments have improved clinicians’ abilities to assess cognition. While these are helpful, the clinician needs to be able go beyond such instruments at times, given their limitations in scope and sensitivity. The Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE) is the most commonly used instrument and its advantages include its widespread use and extensive validation. Disadvantages incl...