eBook - ePub

Organizational Stress

A Review and Critique of Theory, Research, and Applications

Cary L. Cooper, Philip J. Dewe, Michael P O'Driscoll

This is a test

Share book

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Organizational Stress

A Review and Critique of Theory, Research, and Applications

Cary L. Cooper, Philip J. Dewe, Michael P O'Driscoll

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book examines stress in organizational contexts. The authors review the sources and outcomes of job-related stress, the methods used to assess levels and consequences of occupational stress, along with the strategies that might be used by individuals and organizations to confront stress and its associated problems. One chapter is devoted to examining an extreme form of occupational stress--burnout, which has been found to have severe consequences for individuals and their organizations. The book closes with a discussion of scenarios for jobs and work in the new millennium, and the potential sources of stress that these scenarios may generate.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Organizational Stress an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Organizational Stress by Cary L. Cooper, Philip J. Dewe, Michael P O'Driscoll in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Organisational Behaviour. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | What Is Stress? |

To the individual whose health or happiness has been ravaged by an inability to cope with the effects of job-related stress, the costs involved are only too clear. Whether manifested in minor complaints of illness, serious ailments such as heart disease, or social problems such as alcoholism and drug abuse, stress-related problems exact a heavy toll on individuals’ lives (Watts & Cooper, 1998). In addition, it has long been recognized that families suffer directly or indirectly from the stress problems of their members—suffering that can be manifested in unhappy marriages, divorces, and spouse and child abuse. But what price do organizations and nations pay for a poor fit between people and their environments? Only recently has stress been seen as a contributory factor to the productivity and health costs of companies and countries, but, as studies of stress-related illnesses and deaths show, stress imposes a high cost on individual health and well-being as well as organizational productivity (Cooper, Liukkonen, & Cartwright, 1996; Sutherland & Cooper, 1990).

This book examines the concept of stress and its application in organizational contexts. In the following chapters, we review the sources and outcomes of job-related stress, the methods used to assess levels and consequences of occupational stress, and the strategies that might be used by individuals and organizations to confront stress and its associated problems. We also devote one chapter to examining a very extreme form of occupational stress—burnout, which has been found to have severe consequences for individuals and their organizations. Finally, we discuss scenarios for jobs and work in the new millennium, as well as the potential sources of stress that these scenarios may generate.

The major focus of this volume is research on stress arising in job-related, organizational contexts. In each chapter, we examine critical issues concerning stress research and some of the challenges facing researchers in this broad and complex field. Our aim is not to provide a total review of all relevant studies on job stress but to stimulate awareness and critical thinking about significant theoretical and empirical issues. The present chapter begins with a brief overview of the historical origins and early approaches to the study of stress, discusses the strengths and weaknesses of these early approaches, and describes the evolution of the contemporary transactional model of stress. We conclude the chapter with an exploration of emerging themes in the delineation of stress and related concepts.

Overview of Stress Definitions

One difficulty in conducting research on stress is that wide discrepancies exist in the way that stress is defined and operationalized. For instance, the concept of stress has variously been defined as both an independent and a dependent variable (Cox, 1985) and as a “process.” This confusion over terminology is compounded by the broad application of the stress concept in medical, behavioral, and social science research over the past 50 to 60 years. Each discipline has investigated stress from its own unique perspective, adopting as a guideline either a stimulus-based model (stress as the “independent” variable) or a response-based model (stress as the “dependent” variable). The approach taken is dictated by the objectives of the research and the intended action resulting from the findings. What is clear from the different ways in which stress has been defined is that there has been considerable debate and discussion as to what is really meant by stress.

As we discuss in this chapter, the importance of this debate can be established by way of two points. First, theoretical definitions of concepts determine the nature and direction of research, as well as the possible explanations that can be proffered for research findings. Definitions provide researchers with theoretical boundaries that need to be constantly extended and reviewed to ensure that what is being defined reflects the nature of the experience itself (Newton, 1995). Second, the definitional debate gives a sense of time and historical perspective, shedding light on why a certain focus or approach prevails, and a mechanism for considering the explanatory potential of current research.

Almost all research on stress begins by pointing to the difficulties associated with and the confusion surrounding the way in which the term stress has been used. As has already been noted, stress has been defined as a stimulus, a response, or the result of an interaction between the two, with the interaction described in terms of some imbalance between the person and the environment (Cox, 1978). As empirical knowledge has developed, particularly that surrounding the person-environment (P-E) interaction, researchers have considered the nature of that interaction and, more importantly, the psychological processes through which it takes place (Dewe, 1992).

From this debate has emerged a belief that traditional approaches to defining stress (i.e., stimulus, response, interaction) have, by directing attention toward external events, diverted researchers away from considering the processes within the individual through which such events are appraised (Duckworth, 1986). This is not to say that such ideas have gone unresearched or that earlier definitional approaches are necessarily inadequate. However, as knowledge and understanding of stimulus, response, and interaction definitions and their associated meaning have advanced, the debate about how stress should be defined has shifted ground. Rather than singling out and focusing separately on the different elements of the stress process, we suggest that it is now time to examine more comprehensively the nature of that process itself and to integrate stimulus and response definitions within an overall conceptual framework that acknowledges the dynamic linkages between all elements of the stress process.

Contemporary views on how stress should be defined require researchers to think of stress as being relational (Lazarus & Launier, 1978): the result of a transaction between the individual and the environment (Lazarus, 1990). The transactional approach draws researchers toward identifying those processes that link the individual to the environment. What distinguishes this approach from earlier approaches is the emphasis on “transaction”—identifying the processes that link the different components, recognizing that stress does not reside solely in the individual or solely in the environment but in the conjunction between the two, and accepting that no one component (i.e., stimulus, response) can be said to be stress (Lazarus, 1990) because each is part of, and must be understood within, the context of a process.

One last point before considering the different stress definitions in more detail. It should not be assumed that different approaches to defining stress have followed in some logical sequence. A range of factors, including the discipline of the researcher, the direction of the research, and the research questions asked, will influence whether a particular definitional approach is adopted. Furthermore, at the conceptual level many researchers agree that stress should be defined in transactional terms, but empirical research has often adopted definitions that emphasize a particular part of the stress process rather than the nature of the process itself. Despite the confusion in terminology, the important message to emerge is that defining stress is not just an exercise in semantics: The way in which stress is defined has a fundamental impact on how research is conducted and results are explained, and definitions must capture the essence of the stress experience rather than simply reflect a rhetoric (Newton, 1995).

Response-Based Definitions of Stress

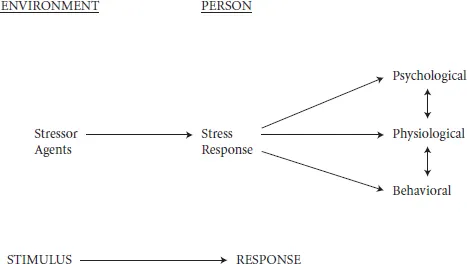

The phrase “being under stress” is one that most people can identify with, although it can mean different things to different individuals. This expression focuses not so much on the nature of stress itself but on its outcomes or consequences. A response-based approach (see Figure 1.1) views stress as a dependent variable (i.e., a response to disturbing or threatening stimuli).

The origins of response-based definitions can be found in medicine and are usually viewed from a physiological perspective—a logical stance for a discipline trained to diagnose and treat symptoms but not necessarily their causes. The work of Hans Selye in the 1930s and 1940s marks the beginning of this approach to the study of stress. In 1936, Selye introduced the notion of stress-related illness in terms of the general adaptation syndrome (GAS), suggesting that stress is a nonspecific response of the body to any demand made upon it (Selye, 1956). Selye’s focus was medical: General malaise was characterized by loss of motivation, appetite, weight, and strength. Evidence from animal studies also indicated internal physical degeneration and deterioration. Responses to stress were considered to be invariant to the nature of the stressor and therefore to follow a universal pattern.

Figure 1.1. A Response-Based Model of Stress

SOURCE: Reproduced from Understanding Stress, Sutherland and Cooper, 1990, Nelson Thornes Ltd.

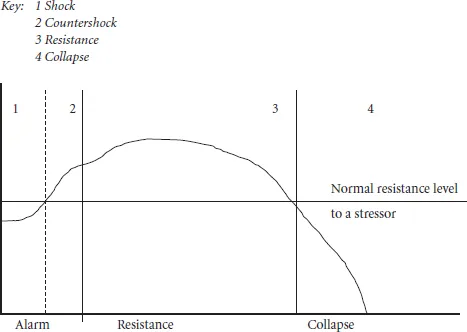

Three stages of response were described within the GAS (see Figure 1.2). The alarm reaction is the immediate psychophysiological response, when the initial “shock” phase of lowered resistance is followed by “countershock.” At this time, defense mechanisms are activated, forming the emergency reaction known as the “fight or flight” response (Cannon, 1935). Increased sympathetic activity results in the secretion of catecholamines, which prepare the body physiologically for action: For example, heart rate and blood pressure increase, the spleen contracts, and blood supplies are redirected to the brain and skeletal muscles. The second stage is resistance to a continued stressor, in which the adaptation response and/or return to equilibrium replace the alarm reaction. However, resistance cannot continue indefinitely, and if the alarm reaction is elicited too intensely or too frequently over an extended period, the energy needed for adaptation becomes depleted, and the third stage (exhaustion, collapse, or death) occurs (Selye, 1983).

Figure 1.2. General Adaptation Syndrome

SOURCE: Selye, The Stress of Life. Copyright © 1956 by McGraw-Hill. Reprinted with permission of the McGraw-Hill Companies.

Although the nonspecificity concept of stress-related illness and the GAS have had far-reaching influence and significant impact on the conceptualization and understanding of stress, they have been challenged (Cox, 1985). Research indicates, for instance, that responses to stimuli do not always follow the same pattern and can be stimulus specific and dependent on the type of hormonal secretion. For example, anxiety-producing situations are associated with adrenalin, whereas noradrenalin is released in response to aggression-producing events. Also, the GAS approach does not address the issue of psychological responses to stress, nor that a response to a potential threat may in turn become the stimulus for another response. In sum, the model is too simplistic. As Christian and Lolas (1985) suggested, the framework of the GAS is still valid for some typical stressors (e.g., the physical factors of heat and cold), but it is not adequate to explain psychosocial stress.

An additional problem associated with the response-based approach is that stress is considered as a generic term that subsumes a large variety of manifestations (Pearlin, Lieberman, Menaghan, & Mullan, 1981). Disagreement exists about the actual manifestations of stress, as well as about where in the organism or system stress is manifested: “Is it in the single cell, in an organ or throughout the entire organism? . . . Biochemical, physiological or emotional functioning? . . . At the endocrine, immunological, metabolic or cardiovascular [level]? . . . Or in particular diseases, physical and psychological?” (Pearlin et al., 1981, pp. 341-342). Clarification of this issue is problematic because the findings of replication research are likely to be confounded. Individuals may adapt to any potential source of stress, so the response will vary over time (e.g., in the assessment of noise on hearing and performance).

Although the word stress usually has negative connotations, Selye (1976) emphasized that stress reactions are not automatically bad and that they cannot be avoided because being alive is synonymous with responding to stress. In fact, a certain level of stress is necessary for motivation, growth, development, and change and has been referred to as eustress. However, unwanted, unmanageable stressor situations are damaging and can lead to distress, or what we will refer to in this book as strain.

As influential as Selye’s ideas were, his approach to defining stress might not now be quite so comprehensive as was first thought. It was not just that different physiological components of Selye’s stress response were inconsistent with the notion of an identifiable response syndrome or the fact that certain “noxious” conditions did not produce the GAS in its entirety. Because of their medical focus, which emphasizes the organism’s response, Selye’s approach and response-based definitions generally have also been criticized because they appear not to consider environmental factors in the stress process. In other words, there has been a tendency to ignore the stimulus dimension of stress experiences.

As early as 1953, Grinker attempted to develop an alternative way of defining stress, based on the idea “that the human organism is part of and in equilibrium with its environment, that its psychological processes assist in maintaining an internal equilibrium and that the psychological functioning of the organism is sensitive to both internal and external conditions” (p. 152). Inevitably, the difficulties associated with the GAS prompted studies where the focus shifted to exploring the external conditions that lead to stress. The result was the formulation of a stimulus-based approach to defining stress, with the emphasis on identifying those events or aspects of events that might cause stress.

Stimulus-Based Definitions of Stress

Identification of potential sources of stress is the central theme of the stimulus-based model of stress (Goodell, Wolf, & Rogers, 1986). The rationale of this approach is that some external forces impinge on the organism in a disruptive way. Stimulus-based definitions of stress have their roots in physics and engineering, the analogy being that stress can be defined as a force exerted, which in turn results in a demand or load reaction, hence creating distortion. If the organism’s tolerance level is exceeded, temporary or permanent damage occurs. The aphorism “the straw that breaks the camel’s back” encapsulates the essence of stimulus-based definitions of stress. An individual is perpetually bombarded with potential sources of stress (which are typically referred to as stressors), but just one more apparently minor or innocuous event can alter the delicate balance between coping and the total breakdown of coping behavior. In short, this model of stress treats stress as an independent variable that elicits some response from the person.

Rapid industrialization provided the initial impetus for this approach, and much of the early research into blue-collar stress aimed to identify sources of stre...