eBook - ePub

Teaching for Wisdom, Intelligence, Creativity, and Success

Robert J. Sternberg, Linda Jarvin, Elena L. Grigorenko

This is a test

Share book

- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Teaching for Wisdom, Intelligence, Creativity, and Success

Robert J. Sternberg, Linda Jarvin, Elena L. Grigorenko

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Based on an extensive research, this practical teaching resource provides instructional and assessment guidelines for strengthening students' higher-order thinking and reasoning skills.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Teaching for Wisdom, Intelligence, Creativity, and Success an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Teaching for Wisdom, Intelligence, Creativity, and Success by Robert J. Sternberg, Linda Jarvin, Elena L. Grigorenko in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Éducation & Méthodes pédagogiques. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Teaching for Wisdom, Intelligence, Creativity, and Success

1

Introduction to Teaching for Wisdom, Intelligence, Creativity, and Success

Part I briefly summarizes the theoretical model of human thinking and reasoning that we believe can provide insight into how students learn best. The theoretical model we refer to is known as “WICS” for Wisdom, Intelligence, and Creativity, Synthesized. We believe that wisdom, intelligence, and creativity are key ingredients in a successful person’s life, and that it is very important in educational settings to help students build on all these skills, in other words, to synthesize them. If you want to learn more about the theory behind the model, we have included an annotated bibliography of articles and books that describe the model more in detail in the Appendix to Part I at the end of this book. There, you will also find references to other authors who have investigated how students learn and offer strategies for teaching different skills such as analysis and creativity in the classroom.

Here we will just briefly review the WICS model, present some arguments for the importance of teaching for intelligence, creativity, and wisdom in the K–12 classroom, and finally, provide a brief self-evaluation scale for you, the reader, to determine your own profile of skills: Are your main strengths in memory, analytical, practical, or creative abilities, or in some combination of them? A scoring key is provided in Answer Key toward the end of the book.

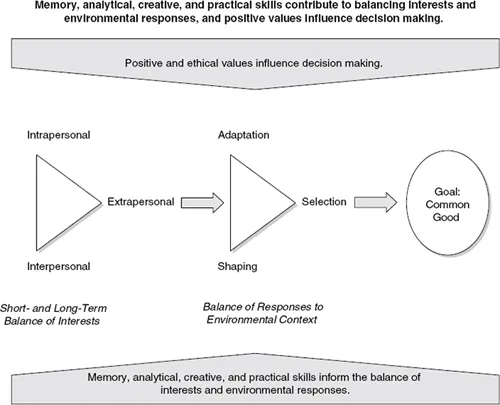

Figure 1.1 gives a visual overview of the WICS model.

Figure 1.1 The WICS Model of Thinking

2

What Is the WICS Model?

The purpose of this book is to serve as a hands-on guide to inspire you to broaden your teaching and assessment repertoire to ensure that all students in your classroom are as successful as they can be. The goal is not to offer you an Introductory Psychology or Intelligence 101 course, but to provide you with suggestions for dealing with some practical and real situations in the classroom.

Before we start, however, we quickly summarize the different theories of intelligence that are in vogue and describe the one we subscribe to, so that you know our position and so that we’re all on the same page. In a nutshell, there are two kinds of theories of intelligence: (1) the single-faceted, unified general intelligence (or g-factor) theories, which emphasize the nature of intelligence as a single entity; and (2) the multifaceted conceptions of intelligence, which emphasize the importance of multiple and distinctive aspects of intelligence.

Those who think that the first type of theory is correct generally view intelligence as relatively fixed and predetermined by genetic endowment, and as relatively independent from schooling. In other words, according to this theory, you are born with a certain amount of smarts, and the type of schooling you receive won’t change it that much. The authors of this book, however, subscribe to the second of these two conceptions of intelligence. Many researchers who are familiar to teachers subscribe to this view, for example, Howard Gardner, the author of the theory of Multiple Intelligences. Investigators in the second group generally agree that intelligence is the flexible capacity to learn from experience and to adapt to one’s environment (using the skills required by and acquired through a specific cultural and social context). They also tend to agree that intelligence can be developed, whether through formal explicit instruction or in informal educational situations (depending on the types of abilities considered). The authors of this book believe that everyone has some initial abilities, and that these can be developed into competencies, and that these competencies can in turn be honed into expertise. We believe that these initial abilities depend in part on genetic heritage, but the manner and degree to which this genetic endowment is realized depends on the individual’s environment. We believe that the key to success in the classroom—and in life more broadly—lies in a combination of intelligence, creativity, and wisdom, as per the WICS model.

We also believe there is an urgent need to teach to all abilities, and to match the assessment of achievement to such broad teaching. The time has come to capitalize on the variety of human resources because students’ talents do not happen to correspond to the skills that schools traditionally have emphasized. Creative and practical abilities are certainly as important in life as are memory and analytical abilities, and they can be as important in school if a school chooses to emphasize these abilities. The next parts of this book will provide you with more details on how to teach and assess for a broader range of abilities, and give you a wealth of concrete examples from classrooms at different grade levels and in different content areas.

Let’s say that, so far, you agree with us that, in order to succeed in life, students need more than rote memorization and the ability to analyze. Let’s say, also, that you think teachers should promote a broader range of skills in their classrooms to help more students of different abilities and learning profiles to succeed. At the same time, you may be asking yourself whether it’s worth trying to implement all these changes and broaden your teaching repertoire. Teachers today are under a lot of pressure and have many constraints related to seeing their students perform well on tests. Indeed, many teachers we have worked with over the years say that although they would like to include more creative activities in their classroom, for example, their school administration is not supportive and emphasizes only the importance of test scores. We all want to promote high achievement in our students, and we think that by broadening your teaching repertoire and addressing the needs of a wider range of students with different learning styles, you will do exactly that. You will help students—all students—achieve at higher levels. Teaching for creativity is not just a nice and fun add-on to the regular curriculum. On the contrary, it is a means to teach content, the content that our local, state, and federal standards and scope and sequence guidelines ask us to teach. In the Appendix to Part I at the end of this book, you’ll find references to studies where we have actually measured whether or not this approach promotes learning (it does!), but for now, let’s just list the four main reasons why the WICS model works for students and teachers.

REASON #1: APPRECIATION OF DIFFERENCES

To teach within the WICS model is to create a supportive learning environment in which students find their own ability patterns, understand how uniqueness allows each individual to make a particular contribution to the learning community, and value diversity. One step toward this goal is to balance the types of activities you offer your students so as to broaden the range of abilities addressed and give more students a chance to capitalize on their strengths (and compensate for their weaknesses). Part III of this book will give you some charts to help you achieve this balance in your classroom.

REASON #2: INCREASING RETENTION OF THE MATERIALS LEARNED

When you teach students through analytical, creative, as well as practical instruction, you enable students to encode information in three different ways (analytically, creatively, and practically), in addition to encoding it for memory. Multiple encodings of information can help improve learning. The portion of this book devoted to teaching for enhancing memory will tell you more about how our memory works.

REASON #3: BUILDING ON STRENGTHS

In a classroom where only one type of skill is addressed (memorization, for example), only one type of learner, memory learners, will feel that they are able to use their strengths to be successful. Students who have strengths in other areas (creativity, for example) will never be able to let those strengths shine in the classroom. If, in contrast, you teach for a broad range of skills, you will give all students a chance to capitalize on their strengths and to compensate for, or correct, their weaknesses. In other words, there should be at least some instruction that is compatible with almost all students’ strengths, enabling students to bring these strengths to bear on the work at hand. Instruction that enables students to capitalize on their strengths is also more likely to motivate students. At the same time, at least some of the instruction will probably not correspond to students’ strengths. It is important also to encourage students to develop modes of compensation for and correction of weaknesses.

REASON #4: INCREASING STUDENT MOTIVATION

Instruction that balances different types of activities addressing different students’ strengths (memory, analytical, creative, practical, and wise thinking skills) will be more motivating to students simply because it makes the material to be learned more interesting. Indeed, when we ask students whose teachers apply the WICS model about their engagement in the curriculum material, we find WICS-based instruction to be effective in capturing the students’ interest. And, we all know that school today competes with a variety of different environmental stimulants and capturing attention of students is difficult, so having a pedagogy that appears to be able to do so is really important for the overall success of schooling.

3

Your Turn

What Is Your Pattern of Strengths?

Now that we have reviewed the different types of abilities the WICS model focuses on, let’s explore your own pattern of strengths, imagining that you are a student. Below, you will find a series of questions about your preferred assessments. This is not a scientific “test”; it’s just one way to start thinking about your own preferred mode(s) of thinking, so that you can keep it in mind when you read the rest of the book and consider your students’ varying patterns of strengths. We are intentionally putting you in a student’s shoes, because typically students are not asked any of these questions because they are not usually given choices similar to those presented below. But, if you find yourself having preferences, so might they! Ready? Let’s go! When you are finished, look at the answer key on page 13.

For each of the questions below, rate on a scale from 1 (low) to 5 (high) how much you would...