![]()

CHAPTER 1

A Whole New World

World markets are unsteady, unemployment is on the rise, housing foreclosures are up, asset values are down, and the political landscape is shifting.

Under such tumultuous conditions people often look to leaders to soothe battered nerves and listen for reassurances portending better days. But in today’s rough and tumble environment, there are reportedly few leaders the average person relies upon.

A GROWING LEADERSHIP CRISIS

According to a recent study, 80 percent of Americans believe there is a major leadership crisis across many industry sectors with only two exceptions; leaders in the military and in medicine still rank relatively high. However, confidence in business leaders fell more than in any other area, including the highly unpopular government sector.1

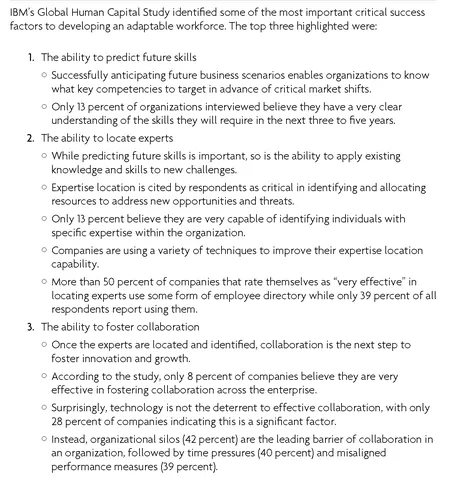

Globally, the crisis of leadership is also taking a heavy toll. IBM reported “companies are heading toward a perfect storm when it comes to leadership,” according to Eric Lesser who led the study. IBM surveyed 400 human resources executives from 40 different countries. In the AsiaPacific region, 88 percent of companies reported concern over their ability to develop future leaders with about 75 percent reporting the same in Latin America, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, as well as 69 percent in North America.2

The growing leadership crisis did not develop overnight. In fact after World War II, optimism, trust, and support for American business leadership soared. Harvard Business School Professor and BusinessWeek writer Shoshanna Zuboff reported that in the mid-1950s, 80 percent of U.S. adults said that “Big Business” was a good thing for the country and 76 percent believed that business required little or no change. By 1966, that number had skidded to 55 percent of Americans who held a high degree of confidence in big company leaders. And by 2006, business leaders’ good will had, for the most part, evaporated. According to a Zogby poll taken that same year, only 7 percent of Americans had a high level of trust in corporate leaders.

It took over half a century for leadership support to sink. But declining trust for executives is not the only trend wreaking havoc with the workforce populace. A completely different organizational landscape has been carved out of the relatively staid and bureaucratic structures of earlier eras. Leaps in technology and its use in global business are at the heart of this colossal shift.

A CHANGED WORKFORCE

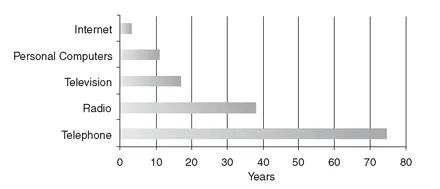

The speed and pace at which technology has forever changed the way we work, with whom, where, when, and how, is practically unfathomable. Out of all recent information and communication technology (ICT), the Internet outpaced all of its predecessors in reaching critical mass. To reach 50 million users it took:

• 75 years for the telephone

• 38 years for the radio

• 17 years for the television

• 11 years for the personal computer

However, it took only 3 years for the Internet to reach over 50 million users, as Figure 1.2 illustrates.

FIGURE 1.1 MoreStartlingStats

Source: IBM Global Human Capital Study: “Looming Leadership Crisis, Organizations Placing Their Companies’ Growth Strategies at Risk.” www-03.ibm.com/press/us/en/pressrelease/22471.wss

FIGURE 1.2 Number of Years to Reach 50 Million Users

Source: Adapted from numbers presented in William McGaughey, Five Epochs of Civilization: World History as Emerging in Five Civilizations (Minneapolis, MN: Thistlerose Publications, 2000).

With the commercial availability of the Internet via browser technology loaded on to every new PC and smartphone rolling off the assembly line, coupled with faster, cheaper, and better access to high-speed telecommunications, came significant corporate leverage of resources. Organizational leaders realized that people could work more efficiently and be free from physical location limitations. This led to higher management expectations of productivity that dovetailed increasingly elevated levels of technological skill across a wide swath of corporate foot soldiers. Not only did applications like spreadsheets and word processors quicken the pace of what had been manually intensive work, but when paired with anytime, anywhere Internet access, people were able to do more work longer.

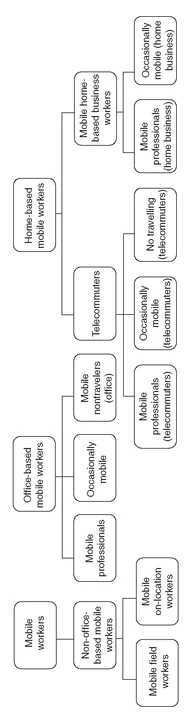

Then came miniaturization. This led to the development of portable laptops, PDAs, and other intelligent computing devices that fit in the palm of a hand. And businesses took advantage. Many soon realized they could tap into mobile labor pools all over the world. In fact, the mobile workforce is rising dramatically. According to the International Data Corporation (IDC), the mobile workforce will increase from about 768 million, or 24.8 percent of the global workforce, to over 1 billion, representing 30.4 percent of worldwide workers by 2011. The largest percentage of mobile workers is in the United States, which had 68 percent in 2006, and is predicted to grow to 73 percent by 2011. Asia/Pacific (excluding Japan) will have the largest number of mobile workers. The region had 480 million mobile workers in 2006, and that number will grow to reach 671 million in 2011—that’s more mobile workers in the region than the Unites States has population!

Substitute the word “mobile” as described by IDC, with the word “virtual,” and you end up with the workforce at the center of this book.

In addition to having unfettered, unbounded access to the virtual workforce, organizations found that labor costs were significantly cheaper outside and it became financially irresistible to increase the use of resources located in countries where pay scales were sometimes a fraction of U.S. wage standards.

The financial impetus to push performance levels ever higher using the newly equipped virtual workforce soon surfaced a glaring need; to change the way organizations were structured. Most organizations today are derivatives of the “vertical” structure. Vertically integrated enterprises are those that are tightly held together from top to bottom using strong, formal hierarchies. In a traditional vertical design all functions reside within the boundaries of the organization. For example, the Human Resources department employs people who work directly for the organization they support. Manufacturing is staffed with people who produce the product the company makes. Sales are made by people who work for the company that produces the goods and whose benefits are managed by the Human Resources department within the same company. In sum, the vertical organization houses everyone needed to produce goods and services as well as support customers and staff.

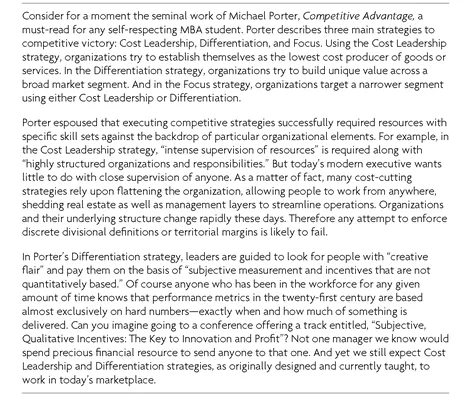

However, the notion of vertical organizations seems almost quaint, like antique furniture staged in an old farmhouse on display for those who have never been near dairy cows. With competitive closeness and cost constraints tightening rapidly, vertical institutions have gone the way of the dinosaur—in reality they have become extinct. Organizational charts and management theories used to describe them are like fossils—relic imprints of organisms long gone. And yet many of today’s most trusted management strategies ironically rely on these petrified frames. This begs the question: Do they still work as designed and should leaders use them as the best way to build lasting success? Figure 1.4 considers these questions.

FIGURE 1.3 The IDC Workforce Hierarchy

Source: Adapted from IDC, 2008

FIGURE1.4 What Does Competitive Advantage Mean Today?

Source: Adapted from Michael E. Porter, Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance, (New York: Free Press, 1998)

While bits of competitive advantage and other management theories are still episodically applicable their essence feels a little like the man behind the curtain in the Wizard of Oz; obscure, antiquated, and in denial. Tried and true they might be; however, inherently these models are based on assumptions that have long since perished.

In his 2006 Foreign Affairs article, Sam Palmisano, Chairman and CEO of IBM, talked about the pressing need for executives to let go of dated conceptualizations of business structures.

Many parties to the globalization debate mistakenly project into the future a picture of corporations that is unchanged from that of today or yesterday. This happens as often among free-market advocates as it does among people opposed to globalization. But businesses are changing in fundamental ways—structurally, operationally, culturally—in response to the imperatives of globalization and new technology. As CEO and chair of the board of IBM, I have observed this within IBM and among our clients. And I believe that rather than continuing to focus on past models, regulators, scholars, nongovernmental organizations, community leaders, and business executives would be best served by thinking about the global corporation of the future and its implications for new approaches to regulation, education, trade, and commerce.

—Excerpt from Samuel J. Palmisano, “The Globally Integrated

Enterprise,” Foreign Affairs, (May/June 2006), 127 [Vol. 85 No. 3]

The structures that many still adhere to belong to an era past; a time when vertical organizations were locked into place in the early part of the twentieth century, guided by gurus like Frederick Winslow Taylor who espoused one-to-one reporting in a top-down closely knit structure with management at the top overseeing the unskilled workers at the bottom. Lattices like these provided the foundation upon which long-term competitive strategies were developed in the context of a market where there still shone a bit of patience; a sense of time and scale about what it would take to bring a product to market and diffuse to the point where the company could claim cornering. But all of that has changed.

Institutional frameworks have morphed into what look more like pancakes; flat, lumpy, and a bit overdone around the edges. They are fueled by highly skilled, specially trained knowledge workers, spread out, communicating side to side, and at the fringe, consist of contractors and other malleable resources that carry no fixed costs and are easily disposed of when belt-tightening is needed. Even so, ask a typical person to draw a picture of their organization and most often they will render a traditional top-down org chart, representing formal hierarchies and reporting relationships. While pictograms of this sort are helpful in seeing who’s who, they no longer represent the relationships that really matter. So organizations are suffering an identity crisis as well as a leadership crisis.

VIRTUAL WORKFORCE DYNAMICS

While massive shifts in organizational structure occur at the macro level, workers are shuffled around much like the ball in a street shell game. With laptops and smartphones in hand, the traditional worker has been downsized, outsourced, right-sized; swept up by the latest merger and assigned a new affiliation or divorced completely from corporate relationships only to re-emerge as an entrepreneur or self-employed consultant hired by the same company. This type of organization looks much more like a network; a network of people linked together by binding ties like deliverables and project assignments, regardless of organizational affiliation. But many still try and shove individuals into boxes on a fossilized diagram with all the performance expectations that come along with tightly integrated formal management processes and assume people will carry out edicts as described by Taylor and others. This view presupposes that because we have really “nifty” collaboration technology it will all “come together at the end of the day.” Yet it doesn’t.

When leaders use old management models to try and solve new challenges and, at the same time expect individuals in social networks, tied together by electronic gadgetry, to behave exactly the same way as they did when grouped next to each other in offices where the organizational chart truly represented the working hierarchy, phantom expectations of leader effectiveness and worker performance emerge and usually miss the mark. The reason—the rise of Virtual Distance.

The Rise of Virtual Distance

The higher one goes in an organization, the more tempting it is to hang on to outdated frameworks, because, let’s face it, they’re straightforward and easy for everyone to understand. And for all the talk and endless books that decree social networks, cro...