![]()

CHAPTER 1

Investing 101

You and I are 50/50 partners in a private equity firm. A friend of ours owns a small manufacturing company that makes outdoor furniture. He wants to retire and has asked us if we would be interested in buying his company. Annual sales are $75 million and he has about 150 employees. He has developed a good management team that will remain after the company is sold. While the U.S. furniture manufacturing industry has been hard hit by low-cost imports, our friend’s business appears to be doing very well. After a tour of the plant and product showroom, we decide it is a good idea to spend some time on an analysis of the company’s business and its financial statements. Our due diligence analysis is focused on one question: What is the likely return we’ll receive on our investment if we buy the outdoor furniture company?

Our investment return from the outdoor furniture company equals the sum of:

1. The difference between the price we pay for the company and the price we receive when we sell it, divided by the price we paid; plus

2. Whatever cash we remove from the company

The cash we take out of the company would be dividends we decide to pay to our firm.

PRICE

The price, both when we buy the company and when we sell it, is primarily determined by two things:

1. The amount of future cash flow the buyer expects the company to generate after the sale closes and

2. The general level of interest rates at the time of the transaction

While we must analyze the company’s historical cash flows to understand the company’s business, when we buy a company we are not buying its historical cash flows. We are buying our right to the company’s future cash flows. The outdoor furniture company’s future cash flows can be divided into two time periods. The first time period is while we own the company. The company’s cash flows while we own it will determine how much cash, if any, we can remove from the company to reinvest or spend as we see fit. The second time period is after we sell the company. Our buyer will estimate the company’s future cash flows and will agree to pay us a price that enables the buyer to obtain the total return the buyer needs in the years after buying the company. Cash flow, unfortunately, is a term that means different things to different people. We will define Free Cash Flow in the next section. The general level of interest rates affects prices of investments. The higher the expected inflation rate during our investment term, the lower the price we should pay for an investment’s future cash flows because there will be fewer goods and services we will be able to purchase with the proceeds (dividends plus the net sale proceeds) of our investment. The lower the anticipated inflation rate, the higher the price we can afford to pay without a decline in the future purchasing power of our investment proceeds.

FREE CASH FLOW

When we purchase 100 percent of a company, we are acquiring the right to all of the company’s future surplus or Free Cash Flow. By

surplus and

free we mean whatever cash remains after the company:

1. Uses cash to pay its operating costs such as employee salaries, wages and benefits, suppliers, utility bills, legal and accounting fees, taxes, interest on debt if any, and so forth

2. Uses cash to extend credit terms to customers and to build inventory, and

3. Uses cash to buy equipment, computers, vehicles, land, and buildings

Once the company has taken care of its obligations in items 1, 2, and 3, the owners—that would be us if we buy the company—can pretty much do what we want with the Free Cash Flow because it is our company. It is not management’s company. Management has little or no equity at risk. Management is compensated by salary and bonuses while we depend entirely on our investment return for our compensation. We can tell management to use the company’s Free Cash Flow to pay dividends to our firm, to buy other companies if we decide that is a smart thing to do, to repay debt if there is any or to buy back the company’s stock.

Now that we have introduced Free Cash Flow, we can refine our definition of investment return by replacing cash flow with Free Cash Flow. Our investment return, then, is (1) the difference between the purchase price and the sale price (both of which are determined by expected Free Cash Flow), divided by the purchase price and (2) the amount of the company’s Free Cash Flow we decide to pay as dividends to ourselves. Each cash dollar the company spends on its operating costs, customer receivables, inventory, new equipment, new buildings, and other purchases is one less dollar of Free Cash Flow. And one dollar less of Free Cash Flow means less return for us, the owners, because investing is a cash business. We invest cash to buy the furniture company. We expect to receive a cash return on our investment. A Net Income return does not help us because our bank does not accept Net Income deposits. Now that we have defined Free Cash Flow, we can get started on determining the price we are willing to pay for the company.

RISK AND RETURN

We use the yields on U.S. Treasury securities to help us set a ballpark purchase price for the outdoor furniture company. A risk assessment of Treasuries is elementary. If the U.S. Treasury cannot return our principal and interest in full and on time, then our money probably is not worth anything anyway. Say we are thinking of owning and running the furniture company for about 10 years. The company generates $10 million of annual Free Cash Flow and is expected to do as well or better over the next few years. We are confident we can cut some costs and reduce capital utilization. To be conservative, we will ignore any such improvements as well as any sales growth potential in our analysis. Assume the 10-year Treasuries are currently yielding 5 percent. Ignoring the effect of interest reinvestment, that is 5 percent of virtually risk-free Free Cash Flow each year for 10 years followed by the return at maturity of 100 percent of our investment. Given all of the risks involved in owning our new company, it is obvious that our anticipated return on our investment in the outdoor furniture company must be substantially higher than the 10-year Treasuries’ 5 percent yield. What if the company were overwhelmed by new competitors and vaporized in three years? We would be left with nothing but the furniture on our patio.

THE RETURN MULTIPLE

We need to decide how much riskier we think our investment in the furniture company is likely to be compared to an investment of the same amount and maturity in U.S. Treasuries. Do we think the purchase of the company is two times, four times, or 10 times riskier than buying Treasuries? Let’s say we think ownership of the outdoor furniture company would be at least four times riskier than owning Treasuries. A 4x Return Multiple means we should be getting four times the Treasuries’ annual 5 percent return, or an annual return of about 20 percent from owning the outdoor furniture company. Many investors expect around a 15 percent return on public company stocks. Our friend’s company is a small private company, so its shares are much less liquid than the shares of a public company. That additional risk suggests a 20 percent return target is not way out of line. As we learn more about the company in our due diligence, we can adjust our Return Multiple up or down if we learn the company’s business offers more or less risk than our original estimate.

RETURN AND PRICE

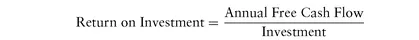

We now know our required return on investment is roughly 20 percent. What price should we pay to generate a 20 percent annual return on our investment in the furniture company? Let’s start with the formula for the simple annual yield, or return, of any investment:

(1.1)

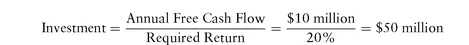

The price we pay for the company is the investment in the formula above. To calculate the investment, we divide $10 million of Free Cash Flow by our required 20 percent return and get an investment, or price, of $50 million:

(1.2)

To keep things as simple as possible, we are not incorporating the time value of money in our calculations. Our investment return formula incorporates:

1. The expected Free Cash Flows generated by the investment

2. The price we are paying for the investment

3. The market’s perception of future risk-free interest rate levels for 10 years

4. The relative risk of the investment (the risk relative to 10-year Treasuries)

Our 4x Return Multiple incorporates items (3) and (4). Our assessment of an investment’s ability to generate Free Cash Flow is our critical starting point because we are investing cash and we want to receive our return in cash. Equally critical is the price we pay for the investment. If we overpay for a company, even for a company with outstanding Free Cash Flow prospects, we may not get our expected return. If we pay $60 million for the company, our return will be 18.75 percent, not 20 percent. Or, in other words, a $60 million price would give us a 20 percent return on the first $50 million. What would our return be on the last $10 million? It would be a zero percent return.

By applying our required 4x Return Multiple to the current Treasuries’ yield for the appropriate term, we are reflecting the market’s expectation of the inflation rate during the term of our investment. Again, the higher the expected inflation rate during our investment term, the lower the price we should pay for the Free Cash Flow we are buying because there will be fewer goods and services we will be able to purchase with the proceeds (dividends plus net sale proceeds) of our investment. The lower the anticipated inflation rate, the higher the price we can afford to pay without a decline in the future purchasing power of our investment proceeds. By comparing our investment’s risk to Treasuries in the Return Multiple, we are attempting to ensure we are sufficiently rewarded for the incremental risk we are taking in our equity investment as compared to our investment in Treasuries. We are taking a lot more risk when we buy stocks and we must receive a lot more return. Comparing our expected return on our acquisition opportunity to a Treasuries’ yield may at first seem strange. Our entire analysis is cash-based. We are investing cash and we expect to receive a cash return. We measure our investment’s value by its Free Cash Flow generation and so we must use a cash benchmark return.

The Return Multiple provides yet another benefit. It helps us manage the chances of paying too much for stocks. This is especially important at the peak of strong equity markets when many investors are overpaying for stocks. In that type of market climate, dependence on comparative Price-to-Earnings ratios (PEs)—almost all of which are too high—leads to rude disappointments. Like all financial metrics, the Return Multiple is by no means foolproof. In periods of financial market turbulence, the utility of interest rates as a proxy for future inflation is sometimes diminished. But the Return Multiple does help us take a step back, a...