![]()

CHAPTER 1

Japan’s Recession

The recovery in Japan’s economy is real, and the signs of an end to the fifteen-year recession are finally here. But it is important to remember that both fundamental and cyclical factors affect the economy. It is only in the former area—those unique problems Japan has struggled with over the past fifteen years—that a genuine recovery is evident. Cyclical or external factors, such as exchange-rate fluctuations, pressures from globalization, especially from China, and financial turmoil in the U.S., also play a role. So although recent data give cause for optimism on the fundamental side, Japan will remain subject to cyclical fluctuations and external pressures.

Chapter 1 sets out to identify the kind of recession Japan has been through, and Chapter 2 examines the ongoing recovery in detail. Global as well as cyclical economic trends are discussed in Chapters 6 and 7.

1. Structural problems and banking-sector issues cannot explain Japan’s long recession

Japan’s recovery did not happen because structural problems were fixed

Much has been said about the causes of Japan’s fifteen-year recession. Some have attributed it to structural problems or to banking-sector issues; others have argued that improper monetary policy and resultant excessively high real interest rates were to blame; and still others have pointed the finger at cultural factors unique to Japan. It is probably safe to say that among non-Japanese observers, many journalists and members of the general public subscribed to the cultural or structural deficiency argument, while academics subscribed to the failure of monetary policy argument. Meanwhile, those in the financial markets subscribed to the banking problem argument as the key reason for the Japanese slowdown.

Those in the structural camp included former Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan,1 who argued that Japan’s inability to weed out zombie companies must be the root cause of the problem, and former Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi, whose battle cry was “No recovery without structural reform.” Although the term structural reform could mean different things to different people, the reform Koizumi and his economic minister Heizo Takenaka had in mind was the Reagan–Thatcher-type supply-side reform. They pushed for supply-side reforms because the usual demand-side monetary and fiscal stimulus had apparently failed to turn the economy around. Late former Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto, who resigned in August 1998, also pushed for structural reform as a means to get the economy going.

Structural problems were also blamed for the five-year German recession lasting from 2000 to 2005, the nation’s worst slump since World War II. That the German economy responded so poorly to monetary stimulus from the European Central Bank (ECB) when other eurozone economies responded favorably supported arguments in favor of structural reforms in Germany.

Among those in the academic camp, Krugman (1998) argued that deflation was the root cause of Japan’s difficulties, even adding that how Japan entered into deflation is immaterial.2 To counter the deflation, he pushed for quantitative easing and inflation targets. This approach of not dwelling on the nature of deflation and jumping right into possible remedies was followed by Bernanke (2003), who argued for the monetization of government debt, and Svensson (2003) and Eggertsson (2003), who recommended various combinations of price-level targeting and currency depreciation. These academic authors argued in favor of more active monetary policy because the past three decades of research into the Great Depression by authors such as Eichengreen (2004), Eichengreen and Sachs (1985), Bernanke (2000), Romer (1991), and Temin (1994) all suggested that the prolonged economic downturn and liquidity trap seen at that time could have been avoided if the U.S. central bank had injected reserves more aggressively.

Although all of these arguments have some merit, that prolonged recessions are extremely rare suggests that something must have been very different about this one. It is therefore critically important to identify the main driver of the fifteen-year recession. In doing so, I will first try to dispel some myths about what happened to Japan during the past fifteen years, and, in the process, examine the applicability of each of the preceding arguments in detail. I will start with the structural and banking arguments because they will lay a foundation for evaluating the remaining monetary policy and cultural arguments.

The slogan “no recovery without structural reform” was made popular by former Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi, who stepped down in September 2006. I will be the first to admit that Japan suffers from numerous structural problems—after all, I provided some of the ideas that went straight into the U.S.-Japan Structural Impediments Initiative that President George H.W. Bush launched in 1991.3 But they could not be the primary reason the nation remained in recession for so long. I do not for a moment believe that an earlier resolution of these problems would have jump-started the Japanese economy. Nor do I think that the privatization of the highway corporations and the post office, the two primary “structural reform” achievements of the Koizumi era, had anything to do with the economic recovery we are seeing today.

How do we know that structural issues were not at the heart of Japan’s long recession? To answer this question, it is first necessary to understand the characteristics of an economy beset by structural problems.

The attempt to seek structural explanations for economic problems is not really old. It was U.S. President Ronald Reagan and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher who first argued that the conventional macroeconomic approach of managing aggregate demand would not solve the economic problems faced by the two countries in the late 1970s. At the time, Britain and the U.S. were veritable hotbeds of structural malaise: workers frequently went on strike, factories produced defective products, and American consumers had begun buying Japanese passenger cars because the locally made alternatives were so unreliable. The Federal Reserve’s attempt to stimulate the economy with aggressive monetary accommodation led to double-digit inflation, and the U.S. trade deficit steadily expanded as consumers gave up poorly made domestic goods for imports. This weighed on the dollar, and aggravated inflationary pressures. Higher inflation, in turn, caused a further devaluation of the dollar. When the Fed finally raised interest rates in a bid to curb rising prices, businesses began to put off capital investment. Such was the vicious cycle in which the U.S. became trapped.

Structural problems point to supply-side issues

In an economy beset by structural problems, frequent strikes and other issues prevent firms from supplying quality goods at competitive prices. Such an economy typically has a large trade deficit, high inflation, and a weak currency, which lead to high interest rates that dampen the enthusiasm of businesses to invest. Its inability to supply quality goods and services stems from micro-level (i.e. structural) problems that cannot be rectified by macro-level monetary or fiscal policy.

But mainstream economists at the time believed that the problems faced by the U.S. and Britain could be solved through the proper administration of macroeconomic policy. Many mocked the supply-side reforms of Reagan and Thatcher as “voodoo economics,” arguing that these policies were little more than mumbo-jumbo, and that Reagan’s arguments should not be taken at face value. Most economists in Japan also held supply-side economics in contempt, deriding Reagan’s policy as “cherry-blossom-drinking economics.” This appellation came from the old tale of two brothers who brought a barrel of sake to sell to revelers drinking under the cherry trees, but ended up consuming the entire cask themselves, each one in turn charging his brother for a cup of rice wine, and then using the proceeds to buy a cup for himself.

Although I was 100 percent immersed in conventional economics in the late 1970s as a graduate student in economics and a doctoral fellow at the Fed, I supported Reagan because I believed that America’s economic problems could not be solved by conventional macroeconomic policy, and instead required a substantial expansion of the nation’s ability to supply goods and services. I still believe that the decision I made at that time was correct. The British economy was undergoing similar problems, and there, too, Prime Minister Thatcher pushed ahead with supply-side reforms.

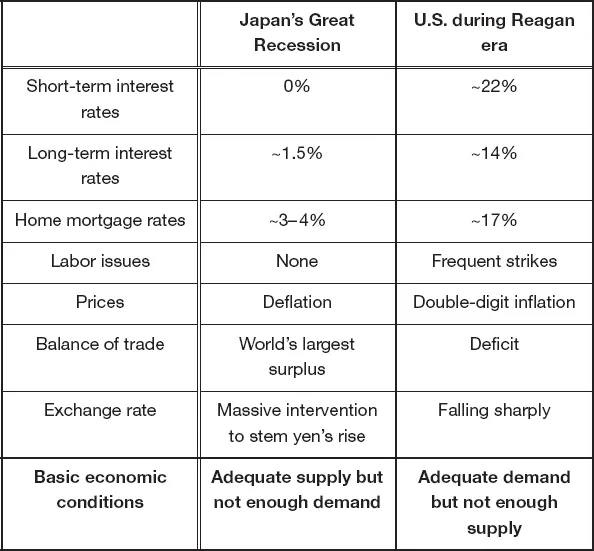

When Reagan took office, the U.S. suffered from double-digit inflation and unusually high interest rates: short-term rates stood at 22 percent, long-term rates at 14 percent, and 30-year fixed-rate mortgages at 17 percent. Strikes were a common occurrence, the trade deficit was large and growing, the dollar was plunging, and the nation’s factories were unable to produce quality goods.

Japan’s economy suffered from a lack of demand

Japan’s economic situation for the past fifteen years was almost a mirror image of that of the U.S. and Britain in the 1980s. Short- and long-term interest rates and home-mortgage rates fell to the lowest levels in history. With the exception of a September 2004 strike by the professional baseball players’ union, there has been almost no industrial action in the past decade. Prices have fallen, not risen. And until recently overtaken by China and Germany, Japan boasted the world’s largest trade surplus. Furthermore, the yen was so strong that in 2003 and 2004 the Japanese government carried out currency interventions totaling ¥30 trillion a year, also a record, to cap its rise.

All these data underscore that Japan’s economy was characterized by ample supply but insufficient demand. Japanese products were in high demand everywhere but in their home market. The cause was not inferior products, but rather a lack of domestic demand.

At the corporate level, Japan’s increasingly robust corporate earnings have gained much attention recently. Yet most of these profits derive from exports, with only a handful of companies gleaning substantial profits from the domestic market. Because domestic sales remain sluggish in spite of heavy marketing efforts, more and more businesses are allocating managerial resources to overseas markets, which boosts foreign sales and adds to the trade surplus. In short, for the past fifteen years Japan has been trapped in a set of circumstances that are the opposite of those faced by the U.S. twenty-five years ago. There has been more than enough supply but not enough demand. So while structural problems did exist, they should not be blamed for the long recession. Exhibit 1-1 compares current Japanese economic conditions with those existing in the U.S. twenty-five years ago.

Japan did not recover because banking sector problems were fixed

It has also been argued that the banking sector was chiefly responsible for the recession. According to this argument, problems in the banking sector and the resultant credit crunch choked off the flow of money to the economy. However, if banks had been the bottleneck—in other words, if willing borrowers were being turned away by the banks—we should have observed several phenomena that are typical of credit crunches.

For a company in need of funds, the closest substitute for a bank loan is an issuance of debt on the corporate-bond market. Even though this option is available only to listed companies, more than 3,800 corporations in Japan could have issued debt or equity securities on the capital markets if they were unable to borrow from banks.

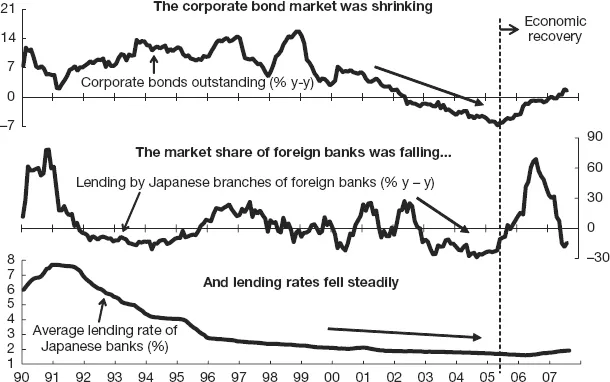

But nothing of the sort was observed during the recession. The topmost graph in Exhibit 1-2 tracks the value of Japanese corporate bonds outstanding from 1990 to the present. Since 2002, the aggregate value of bonds has been steadily declining—in other words, redemptions have exceeded new issuance. Ordinarily, this scenario would be unthinkable with interest rates at zero. Even if we allow the argument that banks for some reason refused to lend to their corporate customers, the companies themselves make the decision whether to issue bonds. If firms sought to raise funds, we should have witnessed a steep rise in the amount of outstanding corporate bonds. In the event, however, the amount outstanding of such debt fell sharply.

Additional evidence undermining this oft-heard argument is provided by the behavior of foreign banks in Japan, which unlike their Japanese rivals faced no major bad-loan problems after the collapse of the late-1980s bubble otherwise known as the Heisei bubble. If inadequate capital and a raft of bad loans did leave Japanese banks unable to lend despite healthy demand for funds from Japanese businesses, foreign banks should have enjoyed an unprecedented opportunity to penetrate the local market. Japan traditionally has a reputation as a tough nut for foreign financial institutions to crack because the choice of banker is so heavily influenced by corporate and personal rela...