eBook - ePub

ABC of Eyes

Peng T. Khaw, Peter Shah, Andrew R. Elkington

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

ABC of Eyes

Peng T. Khaw, Peter Shah, Andrew R. Elkington

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In the three years since the 3rd edition much has changed in the treatment of eye conditions. Glaucoma and macular degeneration, laser treatment compared with surgery, how to deal with refractive errors - all these will be described in detail and illustrated with newly commissioned drawings and photographs.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is ABC of Eyes an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access ABC of Eyes by Peng T. Khaw, Peter Shah, Andrew R. Elkington in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Opthalmology & Optometry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

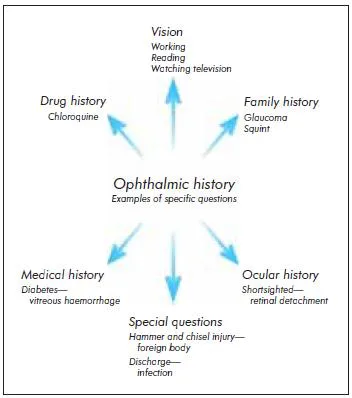

1 History and examination

History

As in all clinical medicine, an accurate history and examination are essential for correct diagnosis and treatment. Most ocular conditions can be diagnosed with a good history and simple examination techniques. Conversely, the failure to take a history and perform a simple examination can lead to conditions being missed that pose a threat to sight, or even to life.

The history may give many clues to the diagnosis. Visual symptoms are particularly important.

The rate of onset of visual symptoms gives an indication of the cause. A sudden deterioration in vision tends to be vascular in origin, whereas a gradual onset suggests a cause such as cataract. The loss of visual field may be characteristic, such as the central field loss of macular degeneration. Symptoms such as flashing lights may indicate traction on the retina and impending retinal detachment. Difficulties with work, reading, watching television, and managing in the house should be identified. It is particularly important to assess the effect of the visual disability on the patient’s lifestyle, especially as conditions such as cataracts can, with modern techniques, be operated on at an early stage.

The patient should also be asked exactly what is worrying them, as visual symptoms often cause great anxiety. Appropriate reassurance then can be given.

Questions about particular symptoms

Some specific questions are important in certain circumstances. A history of ocular trauma or any high velocity injury— particularly a hammer and chisel injury—should suggest an intraocular foreign body. Other questions, for example about the type of discharge in a patient with a red eye, may enable you to make the diagnosis.

Previous ocular history

Easily forgotten, but essential. The patient’s red eye may be associated with complications of contact lens wear—for example, allergy or a corneal abrasion or ulcer. A history of severe shortsightedness (myopia) considerably increases the risk of retinal detachment. A history of longsightedness (hypermetropia) and typically the use of reading glasses before the age of 40 increases the risk of angle closure glaucoma. Patients often forget to mention eye drops and eye operations if they are asked just about “drugs and operations.” A purulent conjunctivitis requires much more urgent attention if the patient has previously had glaucoma drainage surgery, because of the risk of infection entering the eye.

Medical history

Many systemic disorders affect the eye, and the medical history may give clues to the cause of the problem; for instance, diabetes mellitus in a patient with a vitreous haemorrhage or sarcoidosis in a patient with uveitis.

Family history

A good example of the importance of the family history is in primary open angle glaucoma. This may be asymptomatic until severe visual damage has occurred. The risk of the disease may be as high as 1 in 10 in first degree relatives, and the disease may be arrested if treated at an early stage. For any disease that has a genetic component (for example, glaucoma), the age of onset and the severity of disease in affected family members can be very useful information.

Visual symptoms: details to establish

- Monocular or binocular

- Type of disturbance

- Rate of onset

- Presence and type of field loss

- Associated symptoms—for example, flashing lights or floaters

- Effect on lifestyle

- Specific worries

Answers to specific questions in the ophthalmic history will give clues to the diagnosis and help to exclude other problems

A history of a lazy eye (amblyopia) in a patient with a problem with their effective “only” eye is extremely important, as disturbance of vision in the good eye would result in definite functional impairment

A family history of glaucoma is a risk factor for the development of glaucoma

Drug history

Many drugs affect the eye, and they should always be considered as a cause of ocular problems; for example, chloroquine may affect the retina. Steroid drugs in many different forms (drops, ointments, tablets, and inhalers) may all lead to steroid induced glaucoma.

Examination of the visual system

Vision

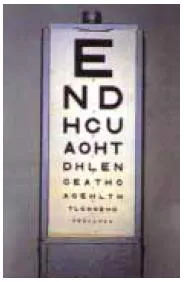

An assessment of visual acuity measures the function of the eye and gives some idea of the patient’s disability. It may also have considerable medicolegal implications; for example, in the case of ocular damage at work or after an assault.

In the United Kingdom, visual acuity is checked with a standard Snellen chart at 6 m. If the room is not large enough, a mirror can be used with a reversed Snellen chart at 3 m. The numbers next to the letters indicate the distance at which a person with no refractive error can read that line (hence the 6/60 line should normally be read at 60 m). If the top line cannot be discerned, the test can be done closer to the chart. If the chart cannot be read at 1 m, patients may be asked to count fingers, and, if they cannot do that, to detect hand movements. Finally, it may be that they can perceive only light. From the patient’s point of view, the functional difference between these categories may be the difference between managing at home on their own (count fingers) and total dependence on others (perception of light).

In other areas of the world (for example, the United States), visual acuity charts use a different nomenclature. Visual acuity of 20/20 is equivalent to 6/6 and 20/200 is equivalent to 6/60. A logarithmic chart (LogMAR) is also used, especially for large scale clinical trials and orthoptic childhood screening. The LogMAR system offers increased sensitivity in acuity testing, but the tests take longer to perform.

Vision should be tested with the aid of the patient’s usual glasses or contact lenses. To achieve optimal visual acuity, the patient should be asked to look through a pinhole. This reduces the effect of any refractive error and particularly is useful if the patient cannot use contact lenses because of a red eye or has not brought their glasses. If patients cannot read English, they can be asked to match letters; this is also useful for young children.

Reading vision can be tested with a standard reading type book or, if this is not available, various sizes of newspaper print. There may be quite a difference in the near and distance vision. A good example is presbyopia, which usually develops in the late forties because of the failure of accommodation with age. Distance vision may be 6/6 without glasses, but the patient may be able to read only larger newspaper print.

Colour vision can be tested by using Ishihara colour plates, which may give useful information in cases of inherited and acquired abnormalities of colour vision. The ability to detect relative degrees of image contrast (contrast sensitivity) is also important and can be assessed with a Pelli-Robson chart. Some eye problems (such as cataract, for example) may cause a significant reduction in contrast sensitivity, despite good Snellen visual acuity.

Field of vision

Tests of the visual field may give clues to the site of any lesion and the diagnosis. It is important to test the visual field in any patient with unexplained visual loss. Patients with lesions that affect the retrochiasmal visual pathway may find it difficult to verbalise exactly why their vision is “not right.”

Assessment of vision

- Snellen chart at 6 m

- Snellen chart closer

- Counting fingers

- Hand movements

- Perception of light

- No perception of light

Testing reading vision

Visual acuity chart

Ishihara colour plate. If a person is colour blind they cannot see the number

Testing the visual field. Ask the patient to cover the eye not being tested. Ensure that the eye is completely covered by the palm

Location of the lesion—Unilateral field loss in the lower nasal field suggests an upper temporal retinal lesion. Central field loss usually indicates macular or optic nerve problems. A homonymous hemianopia or quadrantanopia indicates problems in the brain rather than the eye, although the patient may present with visual disturbance.

Diagnosis—A bitemporal field defect is most commonly caused by a pituitary tumour. A field defect that arches over central vision to the blind spot (arcuate scotoma) is almost pathognomonic of glaucoma.

To test the visual field—The patient should be seated directly opposite the examiner and then should be asked to cover the eye that is not being tested and to look at the examiner’s face. It is essential to make sure that the other eye is covered properly to eliminate erroneous results. In case of a gross defect, the patient will not be able to see part of the examiner’s face and may be able to indicate this precisely: “I can’t see the centre of your face.”

If no gross defect is present, the fields can be tested more formally. Testing the visual field with peripheral finger movements will show severe defects, but a more sensitive test is the detection of red colour, because the ability to detect red tends to be affected earlier. A red pin is moved in from the periphery and the patient is asked when they can see something red.

The pupils

Careful inspection of the pupils can show signs that are helpful in diagnosis. A bright torch is essential. A pupil stuck down to the lens is a result of inflammation within the eye, which always is serious. A peaked pupil after ocular injury suggests perforation with the iris trapped in the wound. A vertically oval unreactive pupil may be seen in acute closed angle glaucoma.

The pupil’s reaction to a good light source is a simple way of checking the integrity of the visual pathways. When testing the direct and consensual ...