![]()

Part I

ON INVESTMENT STRATEGY

Investment strategy is the first issue that investors should consider. At the outset, investing is an act of faith, a willingness to postpone present consumption and save for the future. Investing for the long term is central to the achievement of optimal returns by investors. Unfortunately, the principle of investing for the long term—eschewing funds with high-turnover portfolios and holding shares in soundly managed funds as investments for a lifetime—is honored more in the breach than in the observance by most mutual fund managers and shareholders.

To bring the advantages of long-term investing into focus, I examine here the historical returns, and risks, that have characterized the U.S. stock and bond markets, as well as the sources of those returns: (1) fundamentals represented by earnings and dividends, and (2) speculation, represented by wide swings in the market’s valuation of these fundamentals. The first factor tends to be reliable and sustainable over the long pull; the second is both episodic and spasmodic. These lessons of history are central to the understanding of investing.

This discussion of returns and risks serves as a background for a discussion of asset allocation, now conceded by virtually all thoughtful observers to be by far the most important single decision in shaping the long-term returns earned by investors. Finally, I deal with the paradox that, more than ever in these days of complexity, simplicity underlies the best investment strategies.

![]()

Chapter 1

On Long-Term Investing

Chance and the Garden

Investing is an act of faith. We entrust our capital to corporate stewards in the faith—at least with the hope—that their efforts will generate high rates of return on our investments. When we purchase corporate America’s stocks and bonds, we are professing our faith that the long-term success of the U.S. economy and the nation’s financial markets will continue in the future.

When we invest in a mutual fund, we are expressing our faith that the professional managers of the fund will be vigilant stewards of the assets we entrust to them. We are also recognizing the value of diversification by spreading our investments over a large number of stocks and bonds. A diversified portfolio minimizes the risk inherent in owning any individual security by shifting that risk to the level of the stock and bond markets.

Americans’ faith in investing has waxed and waned, kindled by bull markets and chilled by bear markets, but it has remained intact. It has survived the Great Depression, two world wars, the rise and fall of communism, and a barrage of unnerving changes: booms and bankruptcies, inflation and deflation, shocks in commodity prices, the revolution in information technology, and the globalization of financial markets. In recent years, our faith has been enhanced—perhaps excessively so—by the bull market in stocks that began in 1982 and has accelerated, without significant interruption, toward the century’s end. As we approach the millennium, confidence in equities is at an all-time high.

TEN YEARS LATER

The Paradox of Investing

As the decade ending in 2009 comes to a close, it is hard to escape the conclusion that the faith of investors has been betrayed. The returns generated by our corporate stewards have too often been illusory, created by so-called financial engineering, and produced only by the assumption of massive risks. The deepest recession of the post-1933 era has brought a stop to U.S. economic growth. After two crashes—in 2000-2002 and again in 2007-2009—the stock market returned to the level it reached way back in 1996 (excluding dividends): 13 years of net stagnation of investor wealth.

What’s more, far too many professional managers of our mutual funds have failed to act as vigilant stewards of the assets that we entrusted to them. The record is rife with practices that serve fund managers at the expense of shareholders, from charging excessive fees, to “pay-to-play” (arrangements with brokers who sell fund shares), to a focus on short-term speculation rather than long-term investment. In one of the largest violations of fiduciary duty (as New York attorney general Eliot Spitzer revealed in 2002), nearly a score of major fund managers allowed select groups of preferred investors (often hedge funds) to engage in sophisticated short-term market-timing techniques, at the direct expense of the funds’ long-term individual shareholders.

In any event, 10 years after the turn of the millennium, investor confidence in equities seems to be approaching the vanishing point. My earlier concern that our faith in investing had been excessively enhanced by the long bull market of 982-1999 now seems almost prescient. But when confidence is high, so are market valuations. We can now hope—and, I think, expect—the other side of that coin. When confidence is low, market valuations are likely to be attractive. We might fairly call that parallelism “the paradox of investing.”

Chance, the Garden, and Long-Term Investing

Might some unforeseeable economic shock trigger another depression so severe that it would destroy our faith in the promise of investing? Perhaps. Excessive confidence in smooth seas can blind us to the risk of storms. History is replete with episodes in which the enthusiasm of investors has driven equity prices to—and even beyond—the point at which they are swept into a whirlwind of speculation, leading to unexpected losses. There is little certainty in investing. As long-term investors, however, we cannot afford to let the apocalyptic possibilities frighten us away from the markets. For without risk there is no return.

Another word for “risk” is “chance.” And in today’s high-flying, fast-changing, complex world, the story of Chance the gardener contains an inspirational message for long-term investors. The seasons of his garden find a parallel in the cycles of the economy and the financial markets, and we can emulate his faith that their patterns of the past will define their course in the future.

Chance is a man who has grown to middle age living in a solitary room in a rich man’s mansion, bereft of contact with other human beings. He has two all-consuming interests: watching television and tending the garden outside his room. When the mansion’s owner dies, Chance wanders out on his first foray into the world. He is hit by the limousine of a powerful industrialist who is an adviser to the President. When he is rushed to the industrialist’s estate for medical care, he identifies himself only as “Chance the gardener.” In the confusion, his name quickly becomes “Chauncey Gardiner.”

When the President visits the industrialist, the recuperating Chance sits in on the meeting. The economy is slumping; America’s blue-chip corporations are under stress; the stock market is crashing. Unexpectedly, Chance is asked for his advice:

Chance shrank. He felt the roots of his thoughts had been suddenly yanked out of their wet earth and thrust, tangled, into the unfriendly air. He stared at the carpet. Finally, he spoke: “In a garden,” he said, “growth has its season. There are spring and summer, but there are also fall and winter. And then spring and summer again. As long as the roots are not severed, all is well and all will be well.”

He slowly raises his eyes, and sees that the President seems quietly pleased—indeed, delighted—by his response.

“I must admit, Mr. Gardiner, that is one of the most refreshing and optimistic statements I’ve heard in a very, very long time. Many of us forget that nature and society are one. Like nature, our economic system remains, in the long run, stable and rational, and that’s why we must not fear to be at its mercy. . . . We welcome the inevitable seasons of nature, yet we are upset by the seasons of our economy! How foolish of us.”1

This story is not of my making. It is a brief summary of the early chapters of Jerzy Kosinski’s novel Being There, which was made into a memorable film starring the late Peter Sellers. Like Chance, I am basically an optimist. I see our economy as healthy and stable. It is still marked by seasons of growth and seasons of decline, but its roots have remained strong. Despite the changing seasons, our economy has persisted in an upward course, rebounding from the blackest calamities.

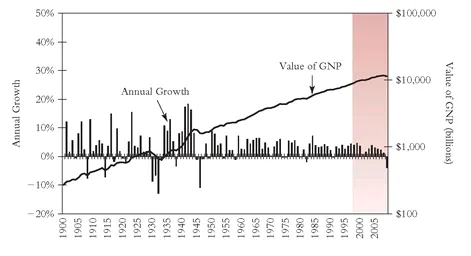

Figure 1.1 chronicles our economy’s growth in the twentieth century. Even in the darkest days of the Great Depression, faith in the future has been rewarded. From 1929 to 1933, the nation’s economic output declined by a cumulative 27 percent. Recovery followed, however, and our economy expanded by a cumulative 50 percent through the rest of the 1930s. From 1944 to 1947, when the economic infrastructure designed for the Second World War had to be adapted to the peace-time production of goods and services, the U.S. economy tumbled into a short but sharp period of contraction, with output shrinking by 13 percent. But we then entered a season of growth, and within four years had recovered all of the lost output. In the next five decades, our economy evolved from a capital-intensive industrial economy, keenly sensitive to the rhythms of the business cycle, to an enormous service economy, less susceptible to extremes of boom and bust.

FIGURE 1.1 Real Gross National Product, 2000 Dollars (1900-2009)

Long-term growth, at least in the United States, seems to have defined the course of economic events. Our real gross national product (GNP) has risen, on average, 3½ percent annually during the twentieth century, and 2.9 percent annually in the half-century following the end of World War II—what might be called the modern economic era. We will inevitably continue to experience seasons of decline, but we can be confident that they will be succeeded by the reappearance of the long-term pattern of growth.

Within the repeated cycle of colorful autumns, barren winters, verdant springs, and warm summers, the stock market has also traced a rising secular trajectory. In this chapter, I review the long-term returns and risks of the most important investment assets: stocks and bonds. The historical record contains lessons that form the basis of successful investment strategy. I hope to show that the historical data support one conclusion with unusual force: To invest with success, you must be a long-term investor. The stock and bond markets are unpredictable on a short-term basis, but their long-term patterns of risk and return have proved durable enough to serve as the basis for a long-term strategy that leads to investment success. Although there is no guarantee that these patterns of the past, no matter how deeply ingrained in the historical record, will prevail in the future, a study of the past, accompanied by a self-administered dose of common sense, is the intelligent investor’s best recourse.

The alternative to long-term investing is a short-term approach to the stock and bond markets. Countless examples from the financial media and the actual practices of professional and individual investors demonstrate that short-term investment strategies are inherently dangerous. In these current ebullient times, large numbers of investors are subordinating the principles of sound long-term investing to the frenetic short-term action that pervades our financial markets. Their counterproductive attempts to trade stocks and funds for short-term advantage, and to time the market (jumping aboard when the market is expected to rise, bailing out in anticipation of a decline), are resulting in the rapid turnover of investment portfolios that ought to be designed to seek long-term goals. We are not able to control our investment returns, but a long-term investment program, fortified by faith in the future, benefits from careful attention to those elements of investing that are within our power to control: risk, cost, and time.

TEN YEARS LATER

The Winter of Our Discontent

Despite the woes encountered by the stock market over the past decade, our economy continued to grow solidly, at a real (inflation-adjusted) rate of 1.7 percent, exactly half the 3.4 per cent growth rate of the modern economic era. Despite the onset of recession in 2008, the gross national product (GNP) actually rose by skinny 1.3 percent for the full year, although a decline (the first since 1991) of about 4 percent is projected for 2009.

But after this winter of our discontent—from mid-2008, through the winter of 2009—we have enjoyed a spring and summer of recovery. For what it’s worth, the stock market provides far more value relative to our economy than was the case decade ago. Then, the aggregate market value of U.S. stocks was 1.8 times the nation’s GNP, an all-time high; by mid-2009, with the value of the market at $10 trillion and the...