![]()

VIII.

$1 Million in Debt; $1 Million Repaid

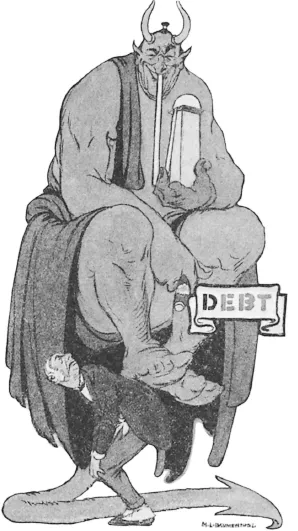

Getting out of debt was more humane in the twentieth century than in previous years. Until the first bankruptcy laws were introduced in Congress in 1800, debtors’ prison was the norm for those who could not pay their debts. The first stock market debacle occurred when the market was conducted outdoors on Wall Street. William Duer, a former Treasury official and patriot during the Revolution, helped bring down the market by becoming vastly overextended in his borrowings and finally going bankrupt. He was sent to debtors’ prison where he died in 1799. A year later Congress passed the first bankruptcy law.

Livingston recalls how his indebtedness was finally paid off by shrewd trading. The stocks he bought and sold were the large cap stocks such as Bethlehem Steel and Anaconda Copper, the ones in which good liquid markets existed. He also reveals how he was short at the time Woodrow Wilson’s peace overtures were reported and how he made strong profits by covering at lower prices because, as he noted, “peace was a bear item.” When the smoke cleared, his long and short positions netted him about $3 million. Being long and then short was part of the strategy, because “a man does not have to marry one side of the market till death do them part.”

The profits helped him pay back his $1 million debt in 1917, although he does allude to the fact that the market did know about the peace overtures before they were made public. The last creditor he paid was the one who had bothered him the most about the unpaid debt: one who was owed only $800. With all debts paid, he was back in the speculation business, with one slight difference from the past.

Using some of his profits, Livingston told Lefèvre that he bought annuities for his family. The old trader’s instincts had matured a bit. If the worst happened again, at least his family would be comfortable.

When Lefèvre asked him why he did it, the answer was simple and somewhat prescient. “But by doing what I did, my wife and child are safe from me,” he admitted. Ironically, Jesse Livermore committed suicide in 1940 in a New York hotel cloakroom. He left a suicide note describing his life as a “failure.” The psychology of the marketplace could exact its toll over a career of speculation.

C.G.

![]()

Reminiscences of a Stock Operator

October 7, 1922

AN OLD Wall Street friend, who had guessed right two out of seven times that week, insisted on my dining with him in the grill room of an uptown hotel much frequented by expert guessers. By dwelling on the two and not on the five he had begun to encourage in himself delusions of financial genius and I had to listen. A man walked past our table, nodded at me and stopped.

I said, “How—d’ye—do?”

He answered, “Tiptop!”

I suspected that I had known him in my Wall Street life, but I could not recall his name.

My loquacious host who had that week landed twice out of seven times, but remembered only the two, saw the stranger and cried, “Hello, Charlie! Dining alone?”

“Yes.”

“Sit down.”

Charlie sat down.

I knew I was safe in remarking, “I haven’t seen you in years.”

“No,” acquiesced Charlie. “What are you doing these days?”

“Trying to keep awake while listening to this man here,” I answered.

I could see that he remembered my face as I remembered his, and no more. The waiter brought him the bill of fare and while he studied it I turned to my friend and soundlessly made my lips ask, “Who is he?”

“Charlie Wade!” whispered my friend, and made a motion with his hands that meant “wiped!”

I had known Wade. He was a broker in my time—one of hundreds. And now he was broke—one of thousands.

Sitting in with the Insiders

MY HOST, who had been speaking of a certain Mexican oil stock, went on:

“It wasn’t luck at all. It was a cinch—because I used my bean. That profit didn’t walk into my pocket of its own accord. The moment I saw that stock cross 160 I knew it wasn’t on covering by pikers, but some big fish about to be harpooned. I preferred sitting in the boat with the impaling insiders to being in the sea doing my little turn as target. That’s all.”

He looked at me, a modest man compelled to listen to the applause of the intelligent audience.

“Was that your first bull’s-eye this year?” I asked.

“The second killing this week,” he retorted with dignity.

But I said pleasantly: “Two hits out of two times at the bat. One hundred per cent sagacious. John W. Gates remarked once in my hearing that all he asked was to be right three out of five times, or 60 percent.”

“And all I ask,” said my friend, “is to be right once out of five times. One in five. Because why? Because when I am wrong I run quick, and when I’m right I push my luck. Each time I’m wrong costs me five thousand at the most. That is, a maximum of twenty thousand for the four wrong times. But when I’m right I do not call it a day’s work this side of a hundred thousand. That’s the reason.”

“A very good reason,” I said.

But I should not have smiled, because he said tartly, “That’s what your friend Larry Livingston does.”

Charlie Wade had finished giving his order to the waiter. He asked me, “Have you read those articles in The Saturday Evening Post about him?”

“He’s the bird that wrote them,” broke in my friend, vindictively pointing at me.

“Oh, did you?” said Charlie.

“You know, he had an account in our office.”

“When?” I asked.

“Oh, that’s more than fifteen years ago. But I’ll never forget how he came to us.”

“I’d like to hear the story,” I said, and meant it.

Charlie looked grateful and spoke.

“My father had been talking of retiring for some time, and while I didn’t want him to think I’d be glad to get rid of him, at the same time I was anxious for a chance to show him what I could do if I was boss. If you remember my father at all you’ll remember that he was a mighty good broker, if I say so myself. It was all he knew how to do, but there weren’t many much better than he. He did a lot of two-dollar business on the floor but he was no man to turn loose on a lot of customers in an office. So I asked nothing better than a chance to run our shop the way it ought to be run, without any grumbling from him. I was doing fairly well, but I had too many handicaps. Think of it! The old gentleman wouldn’t allow me to put in a quotation board in the office! He thought it was too common, too much like a bucket shop!

“I had for an office manager a chap named Giddings. One day I was talking to him about the desirability of having a few really active trading accounts, to enable us to smile gratefully on the hundred-shares-a-month birds we had. I knew that he was a friend of Larry Livingston, the Boy Plunger in Harding’s office. So I said to Giddings, ‘Why don’t you try to get Livingston’s account?’

“‘I have,’ said Giddings.

“‘What did he say?’

“‘Nothing!’

“‘You mean that he didn’t say either yes or no?’

“‘I mean that I haven’t got his business.’

“‘Did you ask him for a part of it?’ I asked.

“‘Not in so many words,’ said Giddings.

“‘Well, then,’ I said, ‘in how many words did you ask him?’

“‘I didn’t ask him in any words. But he knows I’m with this firm and he knows we are members of the New York Stock Exchange and do a stock-commission business. If he wanted to trade through us he’d do it. He doesn’t need to be asked.’

“‘But if you would ask him you’d know if there was any chance of our ever getting any of his business,’ I said.

“‘Charlie, I couldn’t and I wouldn’t,’ said Giddings. ‘He and I are very friendly. But the only way he’ll ever come into this office will be of his own free will and accord. I have never talked stock market with him, nor he with me. I have always felt it would be unwise.’

“I wasn’t convinced, but I couldn’t very well insist. As I told you, my father wouldn’t let us put in a quotation board. He thought that two tickers in the room were enough to keep gentlemen posted on the market, and the other kind he didn’t want hanging around. Well, I was standing beside one of the tickers a few days after my talk with Giddings, when a chap walked in. He was tall and straight, smooth-shaven and very fair-haired.

“He nodded to Giddings, said ‘Hello!’ shortly, and walked over to the other ticker. There wasn’t anybody else in the room at the time. Giddings said ‘Good morning, Larry. How are you?’ very cordially; but Livingston paid no attention whatever to him. He was looking at the tape.

“Pretty soon he looked up and asked abruptly, ‘What sort of execution do you give here?’

“‘As good as you can get from anybody,’ answered Giddings.

“Instantly Livingston put his left hand into his trousers pocket and took out some bills. He counted out five and handed them to Giddings. They were for one thousand dollars each. He began to study the tape again. Pretty soon he put his right hand in his fob pocket, took out a stop watch and said, ‘Buy me five hundred Amalgamated!’

“Giddings shot the order over to the board room. He must have told the old gentleman to get a hustle on, for in a jiffy we got his report. Giddings rushed in and told Livingston what we had got the five hundred Amalgamated for.

“Livingston stopped the watch, looked at it, put it back in his pocket without a word and resumed his reading of the tape. Pretty soon he put his hand into his trousers pocket, fished up some more bills and held them out towards Giddings without taking his eyes off the tape. Then he took out his stop watch again and said, ‘Buy another five hundred!’”

The Boy Plunger at Work

“WHEN we got his report he looked at the stop watch, saw exactly how long it had taken us to get his stock, and doubtless compared prices. Apparently he was satisfied, for he took off his hat and tossed it to Giddings, who hung it on the rack.

“Livingston didn’t speak. He just looked at the tape and smoked one cigar after another without intermission. Before the market closed that day he bought and sold between three and four thousand shares, and was ahead, as I remember, a couple of thousand dollars net on the day’s trading. As soon as the market closed he walked to the hatrack near the door, took his derby and put it on with extreme care, almost as if he had a headache and didn’t wish to make it worse. From the door he spoke to Giddings:

“‘Got a private office you can give me?’

“‘Yes,’ answered Giddings promptly.

“Livingston nodded. ‘Good night,’ he said, and walked out.

“I arranged to have another ticker put in my father’s private office, which we seized for Larry. We had it cleaned up and straightened out, and when Livingston came to trade the next day he found everything ready for him.

“He came in at 9:50. Giddings took him into the private office. Livingston sat down and read all the news slips and bulletins, but made no comments whatever. The moment the ticker began to whir he got up to stand beside it and said, ‘You ought to put in a quotation board.’

“‘We’ll do it,’ said Giddings, who explained to me that Livingston simply had to have both a quotation board and the tape to look at when he traded.

“Well, sir, Livingston bought and sold seventy thousand shares the first week he was in our office. I don’t remember exactly how long he stayed with us, but it was a matter of months. He seemed satisfied with the execution. Then one afternoon without any warning or preamble he said, ‘I’m going away!’ and asked for a check for his balance. He closed his account and never again came into our office. Giddings never knew why he quit us and I never asked Giddings to ask him for an explanation. I saw enough of Livingston to know that he was the kind of man who never did anything without a good reason or mixed business with sentiment. I felt it was useless to ask him to come back to us, so I never even tried. While it lasted it was a mighty profitable business. One day we took in over five thousand dollars in commissions. He sure was the Boy Plunger. We liked him. I never saw him display either anger or impatience—or, for that matter, pleasure. But Giddings used to tell me that he was full of fun and good-natured—outside of Wall Street. It was doubtless his habit of intense concentration that made him so silent in our office.”

“Your soup’s getting cold,” said my friend, and Charlie Wade ceased his reminiscences.

It was not until the next afternoon after the close of the market that I saw Larry Livingston. I told him I wanted more reminiscences, and without appreciable effort he resumed his narrative:

“It has always rankled in my mind that after I left Williamson & Brown’s office the cream was off the market. We ran smack into a long moneyless period; four mighty lean years. There was not a penny to be made. As Billy Henriquez once said, ‘It was the kind of market in which not even a skunk could make a scent.’”

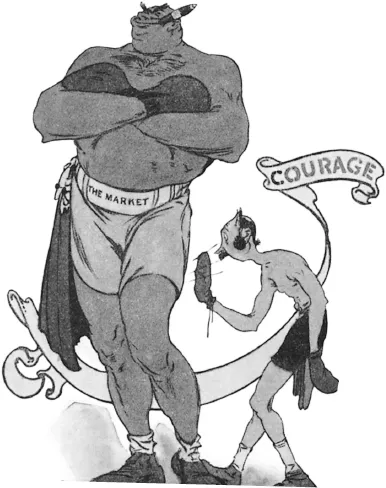

In Dutch with Destiny

“IT LOOKED to me as though I was in Dutch with destiny. It might have been the plan of Providence to chasten me, but really I had not been filled with such pride as called for a fall. I had not committed any of those speculative sins which a trader must expiate on the debtor side of the account. I was not guilty of a typical su...