eBook - ePub

We

How to Increase Performance and Profits through Full Engagement

Rudy Karsan, Kevin Kruse

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

We

How to Increase Performance and Profits through Full Engagement

Rudy Karsan, Kevin Kruse

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Achieve a fully engaged workforce

What if every single employee-every single one-worked in their dream job, utilized their best talents, worked with an inspirational leader and was fully engaged in their role?

For companies, this scenario leads to breakthroughs in productivity, customer service, profitability, and shareholder value. For individuals, it means better health, stronger relationships with family and friends, and greater happiness. We sketches the landscape of today's changing job environment and gives managers and individual employees alike a road map to full engagement.

- Anchored with specific metrics, based on studies of 2 million people, includes engagement, retention, customer loyalty, and profitability

- Scientific research and academic insights are translated into actionable steps

- Authors have extensive experience in cutting-edge human resources solutions

Achieve breakthrough results for yourself and your organization with the power of full engagement from We.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is We an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access We by Rudy Karsan, Kevin Kruse in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part One

Career-Life

For most of human existence, life may have been hard, but it was simple. We ate what we killed, we reaped what we sowed, and later in history we sold what we made. Life was life. But then a funny thing happened—not coincidentally around the time of the Industrial Revolution. People left their villages and farms and moved to get jobs. And “jobs” became something that we did separate from the rest of our life.

Now, we’re shifting back. Societal changes, technology, and our desire to find meaning in what we do is moving us—we should say, returning us—to a Career-Life blend. Although we might wish it weren’t so, our jobs and our lives have become deeply intertwined. Your job impacts not just your wealth but also, more importantly, your health, relationships, and overall happiness. To live in harmony you must understand the seismic shifts taking place in the world of work, and how critical your emotions at work are to everything else you do.

Chapter 1

The Return of the Work-Life Blend

A successful man continues to look for work even after he has found a job.

—Unknown

Pay to Play in the NBA

You don’t have to be a fan of the National Basketball Association (NBA) to appreciate this story about compensation and motivation. . . .

It’s a March evening in Dallas, Texas, and the Denver Nuggets have traveled in to play an important basketball game against the Mavericks. The late season NBA game had all the excitement of two big teams fighting for playoff spots, but this game would have special significance for Earl “J.R.” Smith, a young Nuggets’ player with a knack for landing three-point shots. You see, he knew that on that single night, during that single game, he would earn more money than any other NBA player—a lot more.1

It all started when Smith signed a new three-year contract with the Nuggets, which contained a unique clause specifying a performance bonus. If Smith played 2,000 or more minutes in the season, and the Nuggets won 42 or more games, the Nuggets had to pay Smith a very big bonus. At the time of the negotiations, the Nuggets probably thought it was a safe bet. After all, Smith had played less than 1,500 minutes in each of the previous two seasons. But they structured the deal carefully so that he would be both motivated to consistently contribute throughout the year and to value team success as much as his own play time.

Going into this game, Smith had played for a total of 1,991 minutes in the season. Certainly the fans had no idea of the importance of that number and his teammates were probably oblivious to it, too. But there is no doubt that Smith smiled to himself as each minute of the game clock ticked ever closer—1,998 minutes of total game play, 1,999 minutes, 2,000! J.R. Smith, just 23 years old, earned a $600,000 bonus, the highest game-triggered payout ever.

The Return of Variable Pay

Many people hear about professional sports players’ multimillion dollar contracts, but few realize that most contracts are built on performance clauses very similar to what the Nuggets owners crafted for J.R. Smith. In baseball, fielders are paid bonuses on the number of putout assists and pitchers on the total number of innings pitched. The compensation for an NFL football quarterback is tied to the quarterback rating, which is a formula measuring completions, touchdowns, interceptions, and yards gained. In fact, while this “pay for performance” structure may seem odd to today’s workers who are used to just being paid for their time, it’s actually been the norm in all societies for a long time.

For most of human existence, pay has been tied directly to output. We consumed only what we hunted successfully, later we bartered the crops we harvested and livestock we raised, and still later we would swap the skills we were good at for lodging or meals we needed. Even after the adoption of standardized currencies, we only received it for the goods we made or for specific services (e.g., shoeing a horse). But the industrial revolution and the nature of basic task work inside factories quickly broadened the practice of paying for time rather than performance. Unskilled factory workers were paid wages by the week or by the day, with many people working as many as 16 hours in a 24-hour period. Factory managers were paid by the week. In the 1800s, the English labor movement rallied around a pay-for-time slogan: “A Fair Day’s Wages for a Fair Day’s Work.” In the 1900s, a new army of white-collar office workers began receiving salaries based on annual estimates of time worked.

This two-century long experiment in fixed-payment-for-fixed-time peaked in the 1930s.2 Then slowly but surely, more and more corporations began to introduce variable pay programs for at least part of their workforce. Variable pay refers to compensation systems where a large part of total compensation is performance based, and must be re-earned each year. It is typically tied to the performance of the individual, that person’s team, the employer, or some combination of the three. Payment can be made in cash or sometimes in stock options or stock grants in the company.

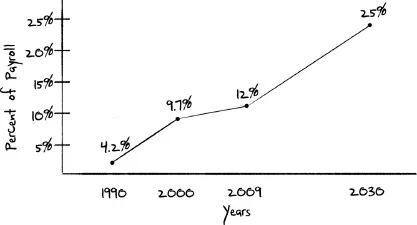

Funding for variable pay programs is now dramatically rising. Figure 1.1 shows how the portion of compensation tied to variable pay has tripled in the last 20 years, increasing from 4.2 percent in 1990 to 12 percent in 2009.3

Figure 1.1 Actual and Projected Variable Pay as Percent of Total Compensation

By the year 2030, we project that fully one-quarter of white-collar pay will be tied to performance and output. This data reflects nonsales compensation; if you were to include sales commissions, these numbers would be in the 35 percent of total pay range.

This dramatic shift to variable pay is an example of We principles at work (see Figure 1.2). Employers benefit from variable pay as it better enables them to manage base costs, reduce risks from unforeseen events, and reward employees whose efforts directly drive business outcomes. Workers benefit from variable pay programs because it can increase their compensation each year far beyond cost-of-living increases and better reward their individual efforts.

Figure 1.2 Advantages of “We Compensation”

Case Study: The Kenexa Z-Index

So how do you actually implement an effective variable pay plan? How do you balance the organization’s goals with the performance of the individual?

At Kenexa, more than 2,000 employees track something called the “Z-Index.” It’s a single number that boils down the organization’s top goals into a single score.

Z-Index = (Sales Backlog + Priority Partner Program Revenue + Enterprise Sales) × Income Percentage × Renewal Rate

This internally is simplified as:

Z = (B + P3 + E) × I × R

The factors that comprise the Z-Index reflect the strategic priorities of the company. Sales backlog represents what’s been sold and committed to, but not yet delivered or earned. Enterprise Sales is a measure of total revenue, P3 is the revenue from the Priority Partner Program, which represents top clients, the contract renewal rate reflects client satisfaction, and income percentage reflects the value of profit. From Rudy in his office near Philadelphia, PA, to the office workers in Vizag, India, and everybody in between, the Z-Index makes crystal clear that Kenexa values profitable growth and client service.

The Z-Index offers a precise answer to the question, “How are we doing as a company?” The Z-Index formula is taught to all new hires, and is reinforced with prominent placement in internal newsletters, posters, and the company’s Intranet, and leaders frequently speak to the score in their team meetings.

Targets are set at the beginning of the year with the Gold Z-Score representing the most ambitious goal, a Silver Z-Score is equal to 90 percent of the gold level, and a Bronze Z-Score reflects 80 percent of the gold level goal (i.e., the bronze goal is 20 percent less than the highest gold-level target). Kenexa senior leadership receives a base pay compensation that is only a fraction of their potential total. The majority of their compensation is variable pay that is tied to both company performance against the Z-Index, and their individual performance against their quarterly and annual objectives. Based on the success of this variable pay plan, compensation plans tied to the Z-Index are being rolled out through the rest of Kenexa.

Managers can use variable pay plans as a powerful tool to attract and retain top talent. For individuals, it offers a higher income potential based on one’s unique talents. Variable pay plans must be designed to balance synergistic interests, just as the contracts of professional athletes reward for both team and individual performance. If a basketball player was only rewarded for three-point shots, he may choose to shoot when he should really pass. If a quarterback was rewarded only for the number of games played, he might choose to avoid hard tackles with a slide instead of diving for the first down. J.R. Smith earned his bonus only if he played a certain number of minutes (the individual goal) and the Denver Nuggets won at least 42 games (the team goal). We-compensation balances the goals of the organization with the goals of the individual.

So Many Jobs

What is most striking about this simple word is that despite 100,000 years of human social evolution, the word job has only been around for the last 400 years. For most of human history, people had one job; they were hunter-gatherers. They moved about from place to place to forage edible plants and hunt game. Eventually, about 12,000 years ago, they learned to domesticate edible plants and animals, thus enabling simple settlements and eventually, they became farmers. Even as settlements flourished and grew in population, most people either tended their crops or were considered herdsmen, moving their cows and sheep across different fields to graze.4

With the Bronze and Iron Ages (approximately 3000 to 500 b.c.) came only a few more job types. Most people were still farmers, but smiths and smelters spent their time turning copper into bronze, traders traveled great distances to barter metals and gemstones, craftsmen built chariots and boats, and professional warriors protected the traders. By the time of Ancient Rome job choice expanded slightly and included priests, scribes, and with an intentional misuse of the word job, you also had slaves. About 1,000 years ago, in the Middle Ages, you could find more service jobs like doctor, bookk...