eBook - ePub

The World Economy

Global Trade Policy 2011

David Greenaway, David Greenaway

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The World Economy

Global Trade Policy 2011

David Greenaway, David Greenaway

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This is the eighteenth volume in an annual series in which leading economists provide a concise and accessible evaluation of major developments in trade and trade policy.

- Examines key issues pertinent to the multinational trading system, as well as regional trade arrangements and policy developments at the national level

-

The 2011 issue analyses global trade policy in areas such as Malaysia, West Africa and China

-

Includes a review of antidumping, safeguards and countervailing duties from 1990–2009

-

Includes chapters exploring WTO issues, and a special section on agricultural trading issues

-

Provides up-to-date assessments of the World Trade Organization's current Trade Policy Reviews

- A vital resource for researchers, analysts and policy-advisors interested in trade policy and other open economy issues

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The World Economy an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The World Economy by David Greenaway, David Greenaway in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Trade & Tariffs. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Trade Policy Review – Malaysia 2010

1. INTRODUCTION

THE objective with this article is to give an academic analysis and assessment of the trade policy situation facing Malaysia. The starting point for the article is the recently completed WTO Trade Policy Review (WTO, 2010a).

Trade Policy Reviews are conducted on a regular basis for all WTO member countries and applicant countries. Malaysia became a member of the WTO on 1 January, 1995. The first review for Malaysia was conducted in 1993, the last in 2005 (Ramasamy and Yeung, 2007). The present review covers the subsequent five-year period 2005–10. The objective with the Trade Policy Review Mechanism launched back in 1988 is to enhance transparency in the area of trade policy by giving an objective overall assessment of the standing of each country’s trade policy regime on a recurring basis vis-à-vis WTO objectives of achieving global free trade (WTO, 2010b).

The article is organised as follows. We start with an introductory note to the Malaysian context of economic policy. Then, in Section 3, we give a general analysis and overview of Malaysia’s trading regime. A main theme of this section is the ambiguity of Malaysia’s development situation. It is argued that several of the dual economy features may be reinforced by present trade-related policies. Despite this Malaysia has diversified her export base since independence. This is a major strength and adds an important element of flexibility in terms of future avenues for specialisation. In the remainder of the paper, we explore three of the areas that are treated as potential strengths or weaknesses of Malaysia’s present trade and development policies by the WTO in the most recent Trade Policy Review document to demonstrate this point.

In Section 4, foreign direct investment policies are reviewed. We discuss whether the present policies and recent changes in the investment regime have been able to recast the structure of costs and benefits of hosting FDI in Malaysia. Section 5 takes a focus on a particular priority sector for Malaysia, which is tourism. We discuss whether policies to promote tourism are wholehearted. What has Malaysia done to bridge dual structures in this sector? We discuss how the Malaysian government has been quite successful in approaching tourism combining a well-designed public policy framework with the dynamic mindset of private entrepreneurs. Section 6 focuses on Malaysia’s external and regional trade partners and the combined challenges of competing in the Asian region under rapidly changing conditions. A short conclusion follows in Section 7.

2. AN INTRODUCTION TO MALAYSIAN ECONOMY AND POLITICS

To understand Malaysia’s economy, a few points about the country have to be borne in mind. Malaysia is a very young nation having only recently embarked on the process of nation building. Prior to the establishment of the union of the Malaysian states (which includes the 11 states of Johor, Kedah, Kelantan, Malacca, Negeri Sembilan, Pahang, Perak, Perlis, Penang, Selangor and Terengganu on the Malaysian peninsula or what is called West Malaysia, the states of Sabah and Sarawak on the island of Borneo or what is called East Malaysia and the three federal territories of Kuala Lumpur, Labuan and Putrajaya), the area that today constitutes Malaysia has been under influence of several outside invading and/or trading nations. In terms of institutions, probably the British left the largest imprint because of the adoption of the Common Law system. However, this system of laws is not being adopted without challenge from other competing systems and influences. Historically, Malaysia has been under the influence of the Muslim world for the longest period in classical and modern times. This has left a colossal imprint on Malaysian culture and traditions. Minor influences are also seen from short periods of European settlements and from a short period of communist rule.

All these influences have left an economic system that can best be described as a mélange of what is today mainly a free market economy combined with a mix of oligarchic style and state ownership. Furthermore, the ethnic makeup of Malaysia also de facto means a large influence from major settlers groups from Asia – especially China and India – which are estimated to make up 30 and 10 per cent respectively of the population. Malaysia also continues to be a popular destination for settlers and international workers from around the Muslim world since it is one of the economically freest Muslim countries in the world (Miller and Holmes, 2011). Indigenous Malay people are estimated alone to constitute around half of the total population. The protection of the rightful interests of the Malay people in the midst of all these outside pressures from what we could think of as ongoing globalisation has been an important factor towards informing economic policies in Malaysia since the 1970s and until today.

Major changes for the economy now and in the future will be more because of the influence that mainland China has directly and indirectly on the Malaysian economy. Whilst linking up to the new economic powerhouse of Asia, Malaysia is also under tremendous pressure of low skilled immigrants from very poor and/or politically unstable neighbouring countries. Few places in the world do we find a scenario of such drastically opposing development circumstances. Within a radius of less than 1,000 km, we can move from countries that count amongst the poorest (Laos, Cambodia and Myanmar) to countries that count amongst the richest (Brunei and Singapore) in the world. Malaysia is exactly the bridge of these very diverse levels of economic development (Hill and Menon, 2010). This situation places unprecedented demands and constraints on economic policies.

3. MALAYSIAN TRADE AND POLICY

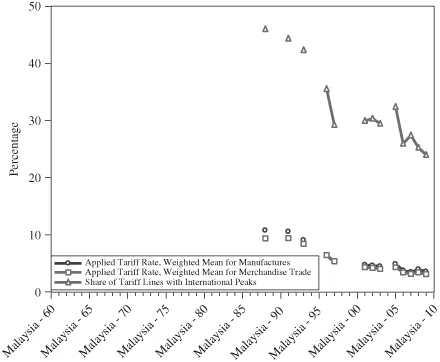

The de facto trade regime in Malaysia may on the surface be characterised as highly liberal, because most instruments used are tariffs and the average incidence of tariffs is relatively low (WTO, 2010a). This is also corroborated by historical data from the WTO but administered by the World Bank as shown with Figure 1.

FIGURE 1 Average Import Tariff Rates and the Share of Tariff Lines with Peaks

Source: The World Bank, World Development Indicators, downloadable at http://www.data.worldbank.org.

However, the indirect trade regime reigning in Malaysia must at the same time be classified as modestly to fairly discriminatory – if we focus on other policies that indirectly affect trade and drive a wedge between domestic and international prices (Menon, 2000; Woo, 2009). A number of such policies are in place today, the most obvious being those that affect different segments of the market for housing and cars (Malpezzi and Mayo, 1997, WTO, 2010a; Wad and Govindaraju, 2011). Indirectly a number of other markets are under similar influence such as the capital market because of the rebates or give-away shares offered to ethnic Malaysians (Woo, 2009). Another example is foreign-based banks that despite the recent reductions in requirements on ownership control operate under different rules compared with their domestic counterparts (WTO, 2010a, p. 58).

These markets function under government administered price discrimination schemes where sorting is sometimes by preferences (cars), sometimes by nationality (housing, banking) and sometimes by ethnicity (housing, investment). The practical implication of these policies is very similar to that of interventionist trade and/or investment policies. Their aim is to do away with dual economy features of the Malaysian economy, whereas in reality, they may be sustaining them. The most pronounced of these are the large differences between rural and urban, followed by differences between the foreign and domestic sectors. Both dimensions of the dual economy also have an ethnic component. These are policies that are considered in the Trade Policy Review to be of particular concern in the context of trade in Malaysia today (WTO, 2010a).

Furthermore, the various types of instruments used combined with a lack of data availability from national statistical sources on important aspects, for example export processing zones or regional economic development data, make the trading regime nontransparent. This was also noted in the recent Trade Policy Review (WTO, 2010a). Similarly, Yusuf and Nabeshima’s (2009) comparative work on Malaysia shows the great lack of knowledge about industries; either industry or firm level data or both are lacking to assess the real situation of competition in the country.

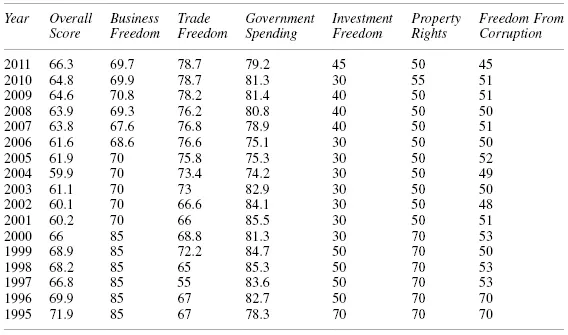

Despite the above, the trading regime of Malaysia is rated as amongst the freest in the world also by international rating houses such as the Heritage Foundation (see third column in Table 1). This is because the incidence of discriminatory policies is not de jure but only de facto related with Malaysia’s external border.

TABLE 1 Economic Freedoms in Malaysia

Source: The Heritage Foundation, downloadable at http://www.heritage.org.

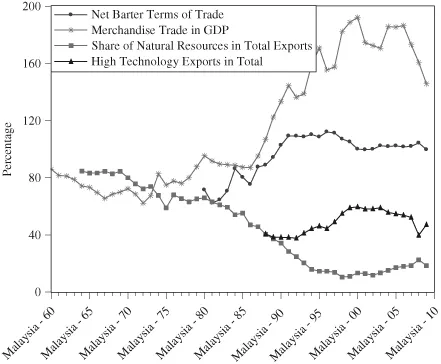

One of the major strengths of the Malaysian economy obtained through its continued commitment to a strong export and outward orientation in its trading environment is the diversity of the export base. Malaysia shows very few traits of a natural resource-dependent developing country today. In 1960, more than 80 per cent of Malaysia’s export revenue is estimated to have accrued from natural resources as shown in Figure 2 using trade data compiled by the World Bank. Today that share has fallen to less than 20 per cent.

FIGURE 2 Trade in GDP, Terms of Trade and Structural Change in Trade

Source: The World Bank, World Development Indicators, downloadable at http://www.data.worldbank.org.

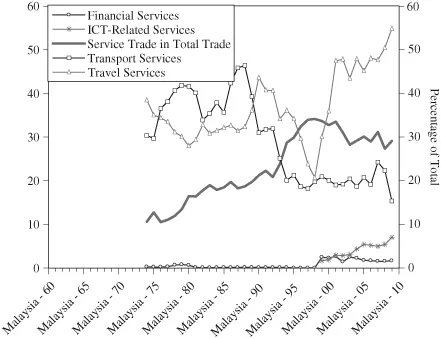

This shows that during the last thirty years, Malaysia has proven capable of spreading its export base towards a large variety of activities. In more recent times, there has been a rapid growth of trade in services, which today constitute around 30 per cent of total trade – well above the average for developing Europe. Whilst lacking separate series for education and health services, the available data on trade in services from the World Bank (Figure 3) show the composition of services trade on different sectors.

FIGURE 3 The Rise of Services

Source: The World Bank, World Development Indicators, downloadable at http://www.data.worldbank.org.

Financial and ICT-related service exports are minor but growing in importance, whereas travel and transport are amongst the dominant exports, which show the significance of the tourism sector to the present strength in services. Also health and education are not unimportant – estimated to be similar in significance to financial services. However, it is clear that at the moment Malaysia has a stronger revealed comparative advantage in basic services or the least knowledge-intensive types such as tourism and travel. According to the 10th Malaysia Plan (EPU, Chapter 2, p. 61, 2nd paragraph):

The services sector is expected to remain the primary source of growth, driven mainly by the expansion in finance and business services, wholesale and retail trade, accommodation and restaurants as well as the transport and communications subsectors.

4. FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT POLICIES

During the colonial period up until independence, Britain is believed to have been one of the largest investors alongside Japan and the United States. However, no data exist to verify this. Upon independence, foreign direct investment received less priority by the first Malaysian governments under Prime Ministers Tun Razak and Tun Hussein Onn. However, this changed and with the Investment Incentives Act of 1968 (Ramasamy, 2003), foreign direct investment along with trade started to receive greater priority. During this era, it was customary in the developing and socialist parts of the world (and this tradition continues to date in the Middle East and parts of Asia) to only invite in foreign investors under certain conditions. The first investment incentive act started an enduring tradition of discrimination between foreign and domestic held capital in Malaysia. Despite this differential and restrictive treatment of foreign investors, Malaysia has been able and especially successful during Prime Minister Mahathir’...