![]()

1

Ethical Issues Regarding the Use of Human Tissues and Cells

Nikola Biller-Andorno1, Diane Wilson2, Ian Kerridge3, and Jeremy R. Chapman3

1University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

2Community Tissue Services, Dayton, OH, USA

3University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Introduction

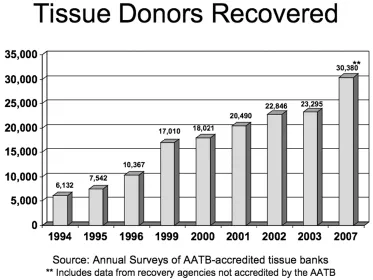

Over the past two decades the use of human tissues and cells for transplantation has steadily increased. In the United States (USA), for example, 2,141,960 tissue grafts were distributed by American Association of Tissue Banks (AATB)-accredited tissue banks in 2007 (2007 AATB Annual Survey Results, Tissue Banks in the United States, May 2010). The AATB reported that tissue donor recoveries in the USA have continued to rise with every survey [1] (Figure 1.1).1 Other countries, such as Spain and Slovakia, have also witnessed a rapid increase in donation of tissues. It is not clear, however, if this increase is in every case a response to need, a consequence of required death referral2 or of other process improvements, or if tissue referral, procurement, and processing are growing as business opportunities.

The field of hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) transplantation has witnessed remarkable development from a highly experimental and risky procedure in the 1970s to a continuing complex procedure with inherent risks but is now a widely applied therapy for a variety of lethal conditions of the bone marrow [2].

This dynamic development is in part due to scientific advances, such as in histocompatibility matching, immunosuppression, and prophylactic treatment of infections. Another reason for the rapidly expanding activities in human cells and tissues for transplantation (HCTT) is the increasing international exchange of these human donations. Collaborative efforts from more than 60 registries of unrelated volunteer bone marrow and other types of HSC donor have expanded the pool of potential donors for these patients from their immediate and extended family through to close to 14 million people globally. The success of some tissue banking systems has led to excess supply and allowed export of certain tissues to countries in need. The export of corneas retrieved in the USA, for instance, has grown from 7% (of the total number of corneas available for transplantation) in 1990 to 29% in 2000 [3]. Anecdotal reports state that 10–15% of the tissue distributed by USA tissue banks (excluding eye banks) is sent outside of the USA. The Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation report in their surveys that more than 80% of the tissue used in Canada is imported from the USA.3

However, data on global use and exchange of tissues are patchy with poor levels of traceability. On the other hand, the unrelated HSC programs are quite tightly controlled by the bone marrow donor registries and cord blood banks, and both activity levels and adverse events data are reported annually by the World Marrow Donor Association (WMDA) (http://www.worldmarrow.org). The World Health Organization (WHO) has also accumulated data on various organ and tissue transplantation rates derived from government sources in its Global Knowledge of Transplantation (http://www.who.int/transplantation/knowledgebase/en).

The idea of transplanting tissues has a longstanding history. A frequent reference is to the legend of Saints Cosmas and Damian, who attempted to transplant a limb from a deceased moor to a white nobleman in the 3rd century AD. Van Meekeren, a Dutch surgeon, reported in 1668 the first successful bone transplant performed on a Russian soldier where a piece of canine skull was used to fill the defect in an injured soldier’s skull. When this transplant was discovered he was excommunicated because the treatment was seen as un-Christian. To return to the good graces of the Church, the soldier asked for the bone to be removed but the graft had already incorporated and healed [4]. Centuries later the surgeon Alexis Carrel expressed his view of the need for organ and tissue transplantation when he stated, “if it were possible immediately after death … to transplant the tissues and organs … no elemental death would occur, and all the … parts of the body would continue to live. A supply of tissues … would be constantly ready for use … and could be sent to surgeons who need them” [5].

From these early times, tissue banking organizations have now grown to many hundreds of establishments providing millions of tissue grafts for transplantation annually, often with excellent success. The early Bone Marrow Registries have grown to more than 70 organizations, and perhaps 200 cord blood banks exist globally. But even if medical advances have allowed cell and tissue transplantations to become standard procedures that are readily accepted by many patients across nations, cultures, and religions, new scientific and ethical challenges have emerged.

One of these challenges is the development of a solid evidence base for clinical and policy decisions regarding HCTT. What is the need and demand for each tissue in each country every year? Can communities be self-sufficient from the tissue donations from their own population? When are cell or tissue transplants the best treatment option, and when is a product being used just as a convenient solution? For example, when is a human heart valve better or worse than a mechanical or a porcine valve? How can governments ensure that precious and rare tissues and cells be optimally used? These issues gain particular importance once donated substances of human origin are highly processed and start to be considered as tradable goods like any other.

The challenge of maintaining both confidentiality and transparency is a responsibility that exists through every step in donation, banking, allocation, and transplantation of human cells and tissues. There has been a longstanding effort in organ transplantation to establish and promote transparency about the availability and allocation of human organs. In tissue transplantation, some health authorities are uncertain of the number of tissue establishments operating in their country, let alone the number of donated, transplanted, exported or imported tissue [6]. Transparency, however, is a key requirement for public trust. This trust is regularly challenged, for example, when bodies or component tissues are reported by the media to have been sold by Funeral Home Directors or when a young patient dies after a dubious experimental stem cell treatment. A clear and well-implemented framework of ethical principles may help avoid such scandals. Detailing how respect for autonomy, stewardship, and fair access to treatment by these special donations is going to be achieved and maintained, together with applying appropriate quality and safety standards, is an important basis for the future development of HCTT.

This chapter outlines major ethical principles and issues of HCTT. It does not enter into issues arising from tissue or cell donation as these have been treated extensively elsewhere [7]. Cell and tissue transplantation are considered separately, as they are in fact two rather distinct fields, while the use of germ line tissues and cells are covered in Chapter 20. The complexity of issues that will need consideration if and when the decision is made to use human embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells (IPS) cells has yet to be defined as the science turns slowly from fiction to fact.

A Normative Framework for HCTT

There are several general ethical rules and principles that cut across the various fields of cell and tissue transplantation and, indeed, organ transplantation. The principle of respect for autonomy requires that any donation be based on informed, voluntary consent. In the case of a deceased donor who in life has not opted out from donation, this may suffice as authorization, but even in presumed consent systems the donor’s family is usually asked for approval, acknowledging the psychological implications a donation may have for them. Also their cooperation is desired for providing a medical and behavioral history.

The concept of stewardship is also inspired by respect for autonomy of the donor: it wishes to honor the intention of the donor – to help another suffering person with his or her gift, a part of one’s own body. Charging unjustifiable fees for processing the cells or tissues or otherwise turning the gift into a commodity just like any other would be incompatible with the idea of serving as the steward of a human tissue or cell gift that one was entrusted with.

Stewardship also requires making optimal use of the donated material. Using the donation in the most efficacious way can also be argued for within the principle of beneficence. Quality and safety requirements, on the other hand, follow from the ethical principle of non-maleficence: risks to the (live) donor, the recipient and third parties are to be minimized. The principle of non-maleficence could also be used to argue against paying donors or their families, as this may encourage dishonesty about the medical history, with the consequence of possible harm to the donor during the donation and to the recipient from an unsuitable product.

Paying for donation could also be considered as being in conflict with the principle of justice. More donors or families with low socio-economic status would respond to financial incentives for donation, whereas high prices for the respective cell and tissue products would favor transplantation of affluent individuals and patients from hig...