![]()

Part One

The Investor: Psychological Traits of the Masters

![]()

Chapter 1

Investment Masters: The Quintet

The best thing that I did was to choose the right heroes.

—Warren Buffett

We start the journey by studying the habits of some investment masters. Habits are critical to success. Many of us have at some point been on a physical fitness jag. We do exercises, follow a certain diet, and set goals (weight, cholesterol level, etc.). Depending on our motivation level, we may even get the desired results. What often happens, however, is that we eventually fail because we cannot break our old habits. We still eat the sweets, butter the bread, skip the workout. Habits are extremely powerful forces in our lives. One psychologist, Earnie Larsen, estimates that as much as 98 percent of our behavior is governed by habits (Larsen, Stage II Recovery, HarperCollins 1985). The point here is that unless we change our habits, our exercise program will have little effect. And if we expect to get different results from doing the same thing over and over, then we are fooling ourselves. Remember the definition of insanity: doing the same thing repeatedly and expecting different results. (For example, mixing SlimFast with Ben & Jerry’s ice cream for your diet breakfast.)

Money managers fall into this “habits” trap all the time. They experience disappointing results at year end and resolve on New Year’s Day that they will do better in the coming year. How? By doing the same things, but more so. They dig faster and deeper in the same dry hole. Why? Because we learn as kids: If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again. Also, mediocre performance tends to makes us a bit nervous (read: pink slip). So, we tighten up and push for results. Studies show us that this pressing limits our flexibility and makes us less likely to try new things. We revert to our most predictable behavior.

Humans love routine, especially when we are under stress. Like lizards that dart out from under a rock, catch a fly, and dart back to safety, we figure out a routine that works and follow it religiously. Edward DeBono, a leading expert on creative thinking, asserts that the biggest myth about creativity is that humans are naturally creative (DeBono, Serious Creativity, HarperCollins 1992). We aren’t. We are creatures of habit. So this is where the definition of insanity applies. Investors must be willing to examine their results and ask, “Is my approach working?” If not, something must change. A mental fitness program for investors would involve identifying and changing unproductive habits.

What would such a program look like? Success in investing depends on the quality of our thinking. That is the skill a superior investor brings to the table. Michael Jordan brought superior physical skills (great agility and great eyesight); Elle McPherson has great physical beauty; Warren Buffett has superior decision-making skills based on his quality of thinking. What components of Buffett’s thinking produce these superior decisions? He reads the same financial press and studies the same finance and investment concepts as most other investors, but somehow he takes those ingredients and bakes a better lasagna. How does he do that?

This book explores that question and offers a mental fitness program for improved results. For those of you who like step-by-step, one-size-fits-all formulas, I’m sorryno can do. As with physical fitness, each person’s program must be tailored to his or her own body and health. But I can explain the concepts so that you can start to tailor your own program.

Returning to the question, “How does he do that?” I chose not only Buffett but also four other investment masters to study. I looked for common threads in their thinking styles, so that use-ful generalizations could be made. The chosen five had to meet three criteria:

1. They had to have exemplary performance records over a long period of time.

2. There had to be enough information available about them so that I could understand and analyze their thinking styles.

3. Their investment approaches had to be sufficiently different from the other four.

The last factor was included because I didn’t want the discussion to end up focusing on the old investment chestnut of growth versus value. (It might devolve into a beer debate: less filling, tastes great, less filling, tastes great …)

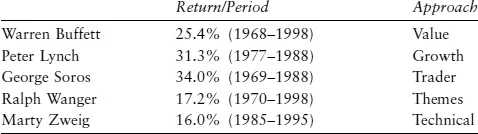

What approach is superior in investing? Evidence indicates that many approaches can win in the market, assuming that the investor has superior decision-making abilities. Figure 1.1 shows the five money masters and their records and approach.

Each of these investors is widely accepted as a master. The question is, what do they do differently? What habits have they acquired that lead to a superior quality of thinking? Can their thinking be replicated?

The premise of this book is that these investors share eight habits in their thinking style, which, in turn, lead to superior results. Can we ordinary mortals do it? Well, there’s good and bad news there: Yes, we can understand and copy it, but not easily.

We live in a culture that promotes instant everything. Faster computers, faster Internet access, faster food service. As with physical fitness programs, this mental fitness program requires a genuine commitment to achieve any real gain. Those who have made that commitment, though, have seen the benefits.

Successful investing, then, is the result of superior thinking combined with a reasonable approach. Different approaches can win in the market. The question becomes this: What qualities or habits do the truly successful investors share? Underneath their educational training, advanced degrees, IQs, and so on, what underlying factors separate them from the rest of us?

Buffett himself says that the differentiating factor is not IQ. And most of us have heard the old joke about Einstein in heaven, where he is asked to share a room with three others:

Einstein to first roomie: “What’s your IQ?”

First roomie: “150.”

Einstein: “Great, we can talk about relativity theory and quantum mechanics.”

Einstein to second roomie: “What’s your IQ?”

Second roomie: “120.”

Einstein: “Good. We can talk about literature and the arts.”

Einstein to third roomie: “What’s your IQ?”

Third roomie: “75.”

Einstein: “Oh. Well, how did the market close today?”

IQ and creative genius are clearly different. Many brilliant in-vestors fail, whereas some with ordinary IQs succeed. Richard Feynman, an excellent model of creative thinking, remarked that it wasn’t such a big deal to win the Nobel prizelots of people had done that. What was a big deal, though, was his winning it with an IQ of only 128! Again, IQ and creative genius are unrelated.

Without further delay, let’s look at the eight habits that these master investors share.

![]()

Chapter 2

The Eight Great Traits

Habit is habit, and not to be flung out of the window by any man, but coaxed downstairs a step at a time.

—Mark Twain

Don’t you hate those books—with titles like “The Secret to Prosperity: Investing in Bull Markets”—that take a simple concept and stretch it over five lifetimes? I read one recently where the author’s point was that leadership involves managing opposing forceslike the interests of shareholders versus the interests of employees. Valid point, but it didn’t require 281 pages to pound it into my brain. So in this chapter, I present the guts of my findings … briefly. That way there will be room for some other neat material in the book and you’ll still be able to finish this by the time the plane lands. Here are the eight great traits of master investors.

1. BREADTH: TAKING IN INFORMATION

Breadth refers to a person’s ability to take in data. Like radar that constantly scans the horizon, these five investors are ravenous for information. Their interests include not only domestic common stocks, but foreign stocks and other asset classesand interests outside of investing as well. Soros, for example, was a philosophy major and is deeply involved in world politics. Lynch is involved in charitable causes.

Consider Peter Lynch’s schedule when he was actively managing the Magellan Fund. He visited with about 50 managements per month, which meant more than 500 per year, traveling more than 100,000 miles. When not traveling, he received upwards of 50 broker calls per day and timed each one with an egg timer. Each salesperson had 90 seconds to make the pitch. Why? Because Lynch was hungry for more information. He wanted to free up the line for the next blip on the radar screen.

2. OBSERVATION: RETAINING DETAILS

Sherlock Holmes once remarked to Watson, “You see, but you do not observe.” What the legendary detective meant, of course, was that Watson did not see the significance of the small clues, the ones that unlocked the mystery. Again, all five of the masters share this capacity for details. This trait is different from the first (breadth). Two analysts might go to the same conference, but one would come away with a wealth of important details, whereas the other might retain very little. Retention of details, then, is key to successful investing. Ralph Wanger remarks, in his book A Zebra in Lion Country (Simon & Schuster 1997), that most research is just plain hard detail work. Likewise, Buffett is famous for his encyclopedic knowledge of the facts. He is able to recite the financial condition of all the businesses in his home town of Omaha, as if their balance sheets were printed on the facades of their buildings.

3. OBJECTIVITY: THINKING CLEARLY

The behavioral finance people have explored this area rather thoroughly, discussing such phenomena as overreaction, overconfidence, anchoring, and the like. Their point is that the economic assumptionthat humans are rational decision makersis false. Rather, we make systematic errors in our thinking that lead to predictable and exploitable investment mistakes.

The most powerful example of this in my experience occurred in 1989. Iben Browning, a climatologist for PaineWebber, predicted that a major earthquake would strike northern California in the fall. Iben was a great presenter, a good storyteller with provocative subjects: earthquakes, tidal waves, and volcanoes. I cannot remember any of his predictions coming true, but he followed the adage: often in error, never in doubt. (My own guess about Iben’s position at PaineWebber is that the firm’s economists wanted him on board to make their economic forecasts appear more credible.) Rather surprisingly, Iben’s prediction about the quake in Northern California proved accurate. Immediately thereafter, Iben’s stock as a forecaster shot up. The Wall Street Journal carried a story about him and his accurate prediction. Soon he issued another warning: that the New Madrid fault, which runs through St. Louis and the Midwest, would shift later that year. (This event was not unprecedented; in the nineteenth century an earthquake occurred in that area and shook church bells as far away as Boston.)

Iben predicted a simila...