![]()

1

Husbandry and Animal Welfare

JOHN WEBSTER

Key Concepts

1.1 Introduction

1.1.1 Traditional agriculture

1.1.2 Industrial agriculture

1.1.3 Value-led agriculture

1.1.4 One-planet agriculture

1.2 Concepts in Animal Welfare

1.2.1 Sentience, welfare and wellbeing

1.2.2 Stress and suffering

1.3 Principles of Husbandry and Welfare

1.3.1 The five freedoms and provisions

1.3.2 Good feeding

1.3.3 Housing and habitat

1.3.4 Fitness and health

1.3.5 Freedom from fear and distress: the art of stockmanship

1.4 Breeding for Fitness

1.5 Transport and Slaughter

1.6 Ethics and Values in Farm Animal Welfare

1.1 Introduction

The broad aim of this book, as in earlier editions, is to provide an introduction to the management and welfare of farm animals through the practice of good husbandry within the context of an efficient, sustainable agriculture. Successive chapters outline these principles and practices for the major farmed species within a range of production systems, both intensive and extensive. This chapter is an introduction to this introduction. It opens with concepts in animal welfare that may be applied to any sentient farm animal, then progresses to general principles that may be applied to their management. These general principles are illustrated by specific examples relating to animal species and production systems (e.g. broiler chickens, dairy cows). For those of you who are new to the study of animal management and animal welfare, some of these examples may only make sense when you have read the chapter on the species to which they refer. I also suggest that, when you have read, learned and inwardly digested a chapter on a particular species, you could refer back to this opening chapter and consider how well (or not) current management practices for that species meet the general criteria for good husbandry and welfare within the categories outlined here.

The purpose of farming is to use the resources of the land to provide the people with food and other goods. The successful farmers are those who have the best idea of what it is the people want and need. Successful livestock farmers are those who also have the best understanding of what it is their animals want and need. Successive chapters will consider the special needs of different farmed species and provide practical advice as to how to meet these needs within the context of viable production systems. The aim of this opening chapter is to introduce principles of husbandry and welfare as they apply to the feeding, breeding, management and care of animals throughout their lives on farms large and small, and in times of special need such as during transport and at the point of slaughter. Most of the meat, milk and eggs for sale to the public in the developed world comes from highly intensive systems in which very large numbers of animals are confined and ‘managed’ by very few people. However, most of the people who actually work with farm animals in most of the world do so within traditional communities where animals are more likely to be cared for on an individual basis. Within the developed world, there is a growing movement to reject industrialized farming methods and return to systems that appear to afford more care and respect to farm animals as individuals.This applies both to those who seek organic, high-welfare or trusted local produce in the shops and to those who wish to farm, whether full-or part-time, to such standards. Of course the fundamental welfare needs of an animal such as a chicken are the same, whether it is scavenging for food in an African village or confined in a controlled environment building containing 100,000 birds. The ethical challenge in either circumstance is how to reconcile the welfare needs of the animals, the needs of the farmers to obtain a fair return for their investment and labour, the needs of the people for safe, high-quality, affordable food and last (but not least) the need to preserve the quality of the living environment.

1.1.1 Traditional agriculture

Agriculture, past, present and future, can be defined by four eras, traditional, industrial, value-led and one-planet. Traditional agriculture, as practised for most of history, and still practised in much of the world today, was low output but sustainable, not least because most of the animals looked after themselves. Sheep and goats consumed fibrous food, unavailable to humans, commonly grazing land the farmer did not own. Chickens and pigs (where culturally acceptable) were fed or scavenged leftovers, and food that humans failed to harvest or elected not to eat. In many traditional communities chickens also fulfilled a valuable community service, consuming ticks and other pests of humans and animals. A dairy cow justified more attention from the farmer (or more likely his wife) who would cut, cart and conserve her feed since she (the cow) was a source of real income through sale of milk. The system seldom generated great riches but it was usually sustainable, partly because it imposed a minimal drain on capital reserves such as fossil fuels, but mainly because nothing was wasted. The use of food and other resources by humans and farm animals was complementary rather than competitive.

1.1.2 Industrial agriculture

It is easy for the well-educated, well-fed citizen of the developed world to paint a rosy picture of traditional agriculture. However, it provided little more than subsistence for most farmers, most of the time, and could not meet our modern expectations for a wide variety of good, safe, cheap food in all seasons. This has been achieved through an industrial revolution in farming that began only about 70 years ago, and only in the industrialized world. In undeveloped countries, it has hardly started. The key distinction between the traditional and the factory livestock or poultry farm is that most or all of the inputs to the latter system – power, machinery and other resources (e.g. food and fertilizers) – are bought in. Thus output is constrained only by the amount that the producer can afford to invest in capital and other resources and the capacity of the system to process them.

The key objectives of industrialized livestock production can be summed up in a single phrase: to control the environment. Feeding involves provision of a nutritionally balanced ration in optimal quantities and at least cost. Housing is designed partly to provide animals with comfort and security, but mainly to maximize income relative to the costs of building and labour. Control of health is achieved through attention to biosecurity and hygiene. These general principles will be developed below and applied to the various species of farm animals in successive chapters.

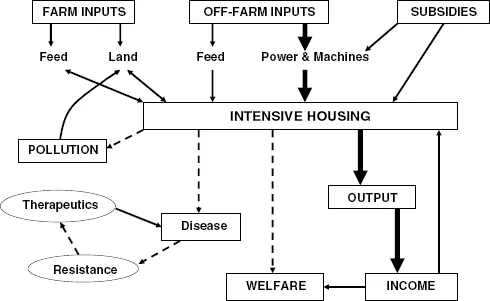

Figure 1.1 outlines the genealogy of the intensive livestock farm, as typified by modern intensively housed pig and poultry units (Webster, 2005). Some feed for pigs and poultry (e.g. cereals) may be grown within the farm enterprise, but this, along with purchased feed supplements to ensure a balanced diet, is trucked onto the unit and dispensed to animals in controlled environment houses by mechanical feeding systems. Mechanical and electrical power is used to control temperature and ventilation, to dispense feed and to remove and disperse the manure. Factory farming was born when it became cheaper, faster and more efficient to process feed through animals using machines than to let the animals do the work for themselves. Once the high set-up costs had been met, the input of cheap energy and other resources from off-farm was able to increase output and reduce running costs. In consequence, poultry meat from chickens and turkeys, once the food of family feasts, is now the cheapest meat on the market.

Potential (although avoidable) harmful outputs from intensive livestock systems (hatched lines in Figure 1.1) include increased pollution, infectious disease and abuse of animal welfare. Bringing animals off the land and into close confinement inevitably increases the risks of infectious disease. To combat this increased risk it has been necessary to introduce strict new strategies to eliminate, or at least reduce, exposure to infection. The key to elimination in an intensive pig or poultry unit is biosecurity. This requires strict controls on the movement of animals and stock-keepers who shower and don protective clothing before entering the unit. This will normally ensure the health of the animals (one essential element of welfare) but there are obvious limits to the expression of natural behaviour in a large isolation hospital. The key element of hygiene is to minimize contact between animals and their excreta.

Where exposure to infection cannot be eliminated through exclusion or hygiene, it is necessary to develop routine disease control measures through the use of vaccines, antibiotics and antiparasitic drugs. If access to cheap power had been all that was necessary for the success of intensive livestock farming, then this industrial revolution would have happened in the 1920s. In fact the greatest rate of expansion only occurred in the 1950s when antibiotics effective against the major endemic bacterial diseases of housed livestock became cheap and freely available. Alternative, subtler approaches to disease control, such as the development of specific vaccines and strains of animals genetically resistant to specific diseases, have also contributed to the commercial success of intensive systems, especially in the case of poultry. However, it is fair to claim that industrialized farming of pigs and poultry has, for the last 50 years, been sustained by the routine use of antibiotics, coccidiostats and other chemotherapeutics to control endemic diseases. In some cases these diseases could be life threatening. In most cases, however, chemotherapeutics have been used routinely to increase productivity by reducing the effects of chronic, low-grade infection.

In Europe there is now a ban on the routine use of antibiotics and many other chemotherapeutic ‘growth promoters’, mainly on the basis of concern that the development of microbial resistance to antibiotics used as growth promoters will pose an increasing risk to human health. The scientific evidence in support of this legislation is inconsistent. However, on balance, and in time, it has to be a good thing, both for the animals and ourselves, to restrict the routine use of antibiotics in livestock agriculture. It is an unequivocal insult to the principle of good husbandry to keep animals in conditions of such intensity, inappropriate feeding or squalor that their health can only be ensured by the routine administration of chemotherapeutics.

Although the industrial farming of livestock and poultry does present opportunities, assessed in terms of animal health and welfare, it also presents inherent threats. It is obviously impossible to care for each chicken as an individual within a poultry house containing over 100,000 animals. Any individual that falls behind the average by virtue of ill health, impaired development or reluctance to compete at the feed trough has little chance of being nursed back to normality through sympathetic stockmanship.

1.1.3 Value-led agriculture

The main impact of industrial agriculture has been to provide an ample supply and wide, year-round choice of food that is reliable, safe and cheap, and looks and tastes good. This is what most of the people have wanted most of the time. However, in recent years and within societies that can afford such morals, consumers have begun to display an increasingly compassionate concern for other, less tangible, elements of food quality, especially animal welfare and the quality of the environment. Farmers and retailers involved in livestock production have responded to this demand by developing alternative husbandry systems that give increased attention to animal welfare and environmental sustainability through developments and improvements to husbandry. The development of such alternative systems will be a feature of this book. It is however, necessary to point out at the outset that the amount of care that farmers can give to the welfare of both their animals and the land is constrained by what they can afford. If society wishes to give added value to such things as animal welfare and the environment, then society must pay for it.

1.1.4 One-planet agriculture

The aim of good husbandry has always been two fold: to provide a good food and other goods for humans, while at the same time sustaining the quality of the land and the life of the land. In the future, the pressure on agriculture throughout the world, intensive and extensive, will increasingly be driven by the need to sustain the living environment. This may challenge our current, comfortable feelings of compassion for other sentient creatures, farm animals, wildlife and poor people. The challenge will be to sustain improvements in animal welfare within the context of animal production systems that are efficient in use of resources, do not pollute the soil and waterways, and restrict the production of green house gases, especially from ruminants. This book outlines the basic principles that define our duty of care to farm animals and the practices that contribute to their management. However, these principles and practice can never be divorced from the primary need to ensure the economically competitive production of food and other goods, while sustaining the productivity and quality of the living environment. This being so, compromise is inevitable. An ethical approach to such compromise is presented in the closing section of this chapter.

1.2 Concepts in Animal Welfare

The expression ‘animal welfare’ has two distinct meanings. The first is a description of the physical and mental state of an animal as it seeks to meet its physiological and behavioural needs. It is a measure of welfare as perceived by the animal itself and something that we can study through careful observations of animal behaviour and the disciplines of welfare science. The second concept of animal welfare is as an expression of moral concern. It arises from the belief that animals can experience feelings that we would interpret as pain and suffering, thus we have duty to protect animals in our care from these things. A concern for animal welfare is obviously a virtue. It is good that we should care about animals. Caring for animals, however, involves more than virtue; it requires a sound understanding of the principles of husbandry and welfare and these things can only be acquired through education and practical experience. This book is aimed mainly at those who will have direct responsibility for the care of farm animals. However, the moral responsibility to provide a duty of care does not apply only to those directly involved with animals on the farm, in transport and at the place of slaughter. The responsibility must be shared by all who, directly or indirectly, derive any value from the exploitation of animals to suit their ends, whether for food, clothing, sport or companionship. These responsibilities may be outlined as follows:

1. to acknowledge and understand the concepts of welfare, sentience and suffering in farm animals;

2. to breed and manage farm animals so as to promote good welfare and avoid suffering throughout their working lives;

3. to increase public awareness of the welfare needs of farm animals, within a context that also recognizes the needs of farmers to produce good food and maintain a decent living through the practice of good husbandry: the competent and caring management of the land and the life of the land;

4. to work towards improved standards of farm animal welfare through the parallel development of improved husbandry systems and increased public demand for food and other goods produced to these higher standards.

1.2.1 Sentience, welfare and wellbeing

Animal welfare has been defined as ‘the state of an animal as it attempts to cope with its environment’ (Fraser and Broom, 1990). The definition may be applied to any animal from an ant to an ape. Farm animals, however, have been classified, at least within the European Union, as ‘sentient creatures’, a definition that acknowledges that their welfare is defined by their success in meeting both their physiological and behavioural needs. For farm animals therefore the definition of welfare becomes ‘the state of body and mind of a sentient animal as it attempts to cope with its environment’. This definition covers the full spectrum of welfare from healthy to sick, pain to pleasure. The aim of the sentient animal is to achieve a state of good welfare, or wellbeing, defined simply as ‘fit and happy’ or ‘fit and feeling good’ (Webster, 2005). This, too, is a state of body and mind. For the body it implies sustained health; for the mind it implies, at least, an absence of suffering from such things as pain, fear and exhaustion. Ideally it should embrace a sense of positive wellbeing (feeling good) achieved by such things as comfort, companionship and security.

Animal sentience involves feelings. It also implies that these feelings matter. Marian Dawkins (1990) has pioneered the study of motivation in animals by seeking to measure how hard animals will work to achieve (or avoid) a resource or stimulus that makes them feel good (or bad) (see Chapter 2). So far as animals are concerned, sentience may therefore best be defined as ‘feelings that matter’ (Webster, 2005). This definition recognizes that the behaviour of animals is motivated by the emotional need to seek satisfaction and avoid suffering. Many of these emotions are associated with primitive sensations such as hunger, pain and anxiety. Some species may also experience ‘higher feelings’ such as friendship and grief at the loss of a relative, and this may expand the nature of their sentience. However, we should not assume that the distress caused to animals by the emotions of hunger, pain and anxiety is any less intense because they are primitive.

Figure 1.2 illustrates how sentient animals perceive their environment and how this motivates their behaviour (Webster, 2005). The ‘control centres’ in the central nervous system (CNS) constantly receive informati...