![]()

1

Introduction to the Land and Its People

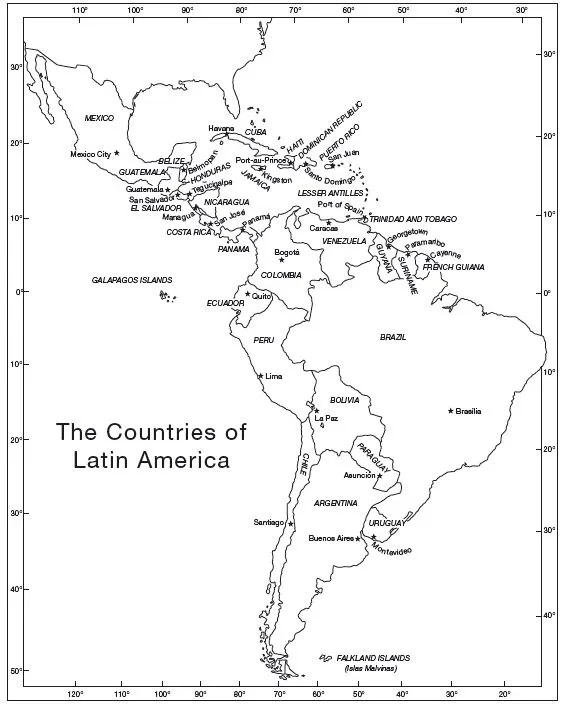

Latin America is a vast, geographically and culturally diverse region stretching from the southern border of the United States to Puerto Toro at the tip of Chile, the southernmost town of the planet. Encompassing over 8 million square miles, the 20 countries that make up Latin America are home to an estimated 550 million people who converse in at least five European-based languages and six or more main indigenous languages, plus African Creole and hundreds of smaller language groups.

Historians disagree over the origin of the name “Latin America.” Some contend that geographers in the sixteenth century gave the name “Latin America” to the new lands colonized by Spain and Portugal in reference to the Latin-based languages imposed on indigenous people and imported African slaves in the newly acquired territories. More recently, others have argued that the name originated in France in the 1860s under the reign of Napoleon III, as a result of that country’s short-lived attempt to fold all the Latin-language-derived countries of the Americas into a neocolonial empire. Although other European powers (Britain, Holland, and Denmark) colonized parts of the Americas, the term “Latin America” generally refers to those territories in which the main spoken language is Spanish or Portuguese: Mexico, most of Central and South America, and the Caribbean islands of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Dominican Republic. The former French possessions of Haiti and other islands of the Caribbean, French Guiana on the South American continent, and even Quebec in Canada, could be included in a broadened definition of Latin America. However, this book defines Latin America as the region that fell under Spanish and Portuguese domination beginning in the late fifteenth and into the mid-sixteenth centuries. The definition also encompasses other Caribbean and South American countries such as Haiti and Jamaica among others, since events in those areas are important to our historical narrative. This definition follows the practice of scholars in recent years, who have generally defined Latin America and the Caribbean as a socially and economically interrelated entity, no matter what language or culture predominates.

Geography

Latin America boasts some of the largest cities in the world, including four of the top 20: Mexico City, São Paulo (Brazil), Bogotá (Colombia) and Lima (Peru). When defined by greater metropolitan area – the city plus outskirts – Buenos Aires (Argentina) and Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) join the list of the world’s megacities, the term for a metropolis of more than 10 million people. Population figures, however, are controversial since most of these gigantic urban centers include, in addition to the housed and settled population, transitory masses of destitute migrants living in makeshift dwellings or in the open air. It is hard for census takers and demographers to obtain an accurate count under those circumstances.

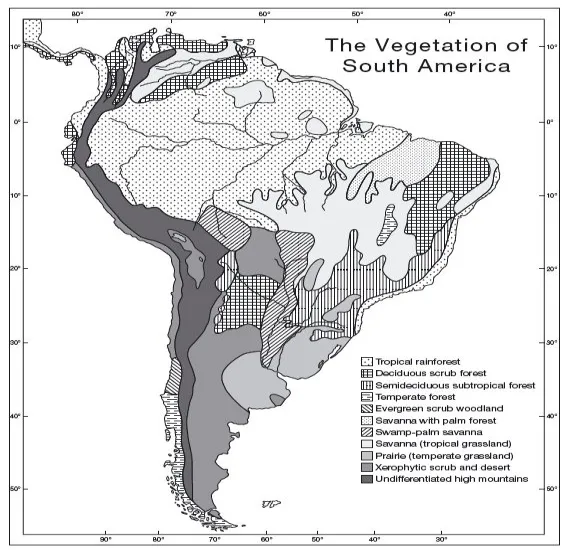

Not only does Latin America have some of the largest population centers in the world, but its countryside, jungles, mountains, and coastlines are major geographical and topographical landmarks (see Map 1.1). The 2-million-square-mile Amazon Basin is the largest rainforest in the world. Spanning the far north of Brazil, stretching into Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, French Guiana, Guyana, Suriname, and Venezuela, it is home for approximately 15 percent of all living species on the planet. South and to the east of the Amazon Basin in the Brazilian state of Mato Grosso lays the Pantanal, the world’s largest wetlands. Other superlatives include the highest mountain range of the Americas (the Andes) that stretches nearly the entire length of the continent; second in the world to the Himalayas of Asia in height, the Andes are much longer, geologically younger, and very seismically active. The Andean peak Aconcagua in Chile is the highest mountain in the Americas, which at 22,834 ft. exceeds Dinali (Mt. McKinley) in Alaska by over 2,000 ft. The Atacama Desert, spanning Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile, is the driest place on earth and the largest depository of sodium nitrates on the planet. Elsewhere in the Andean region is Lake Titicaca, the most elevated navigable body of water in the world. This huge lake forms the boundary between Peru and Bolivia, and the Bolivian city of La Paz is the world’s highest-altitude capital city. Angel Falls in Venezuela is the highest waterfall in the world; at 3,212 ft. it is almost 20 times higher than Niagara Falls. Angel Falls connects through tributaries to the world’s largest river (in volume), the Amazon. In its 25,000 miles of navigable water, this mighty “River Sea,” as the Amazon River is called, contains 16 percent of the world’s river water and 20 percent of the fresh water on Earth.

People

The sheer diversity of the population of Latin America and the Caribbean has made the region extremely interesting culturally, but has also affected the level of economic and political equality. Latin America is exceedingly diverse, a place where the interaction, cross-fertilization, mutation, interpenetration, and reinvention of cultures from Europe, Asia, Africa, and indigenous America has produced a lively and rich set of traditions in music, art, literature, religion, sport, dance, and political and economic trends. Bolivia, for example, elected an indigenous president in 2005 who was a former coca leaf farmer. President Evo Morales won easily with the backing of poor and indigenous Bolivians but has met hostility from wealthy and middle-class citizens who benefited from the country’s natural gas exports and follow more “Western” traditions. Thus ethnic and racial strife has accompanied synthesis and cultural enrichment as cultures continue to confront each other more than 500 years past the original fifteenth-century encounter. (See Map 1.2.)

In Bolivia and Peru people who trace their ethnicity back to the pre-Columbian era constitute the majority, while in Colombia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, and Venezuela people of mixed European and indigenous ancestry, known as mestizos, constitute the majority. Africans were imported as slaves from the sixteenth until the mid-nineteenth centuries, and their descendants still comprise over half of the population in many areas. People in the Caribbean islands of Cuba, the Dominican Republic, and Puerto Rico, as well as in many South American nations, especially Brazil, are descendants of a mixture of Africans and Europeans, called mulattos or Afro-descendant, a more appropriate term that refers to heritage rather than race. Blacks are in the majority in Haiti and in many of the Caribbean nations that were in the hands of the British, Dutch, French, or other colonial powers. Everywhere in Latin America there is evidence of racial mixture, giving rise to the term casta, which the Spaniards used to denote any person whose ancestors were from all three major ethnic groups: indigenous, European, and African. Although this has a pejorative connotation in some regions, the creation of such a term suggests that racial mixture in Latin America is so extensive as to make it often awkward, and imprecise, to list each combination.

Large numbers of Europeans immigrated to Latin America in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In addition to the majority who came from Spain, Portugal, and Italy, immigrants arrived from France, Germany, Poland, Russia, and the Middle Eastern countries of Turkey, Syria, and Lebanon; a large number of Eastern European and German Jews sought refuge in Latin America both before and in the years immediately after World War II. Many European migrants settled in the Southern Cone countries of Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, and the southernmost region of Brazil. Japanese also immigrated to Brazil, especially to São Paulo, where they were resettled on coffee plantations and eventually moved into urban areas to form the largest community of Japanese outside Japan. In addition, Japanese moved in large numbers to Peru, while Koreans and Chinese migrated to every part of Latin America. Chinese and East Indians were brought as indentured servants to many of the countries of the Caribbean region beginning in the nineteenth and extending into the twentieth century.

Because race in Latin America was from the earliest days of the arrival of Europeans identified along a continuum from indigenous and black at one end and white Europeans at the other, any discussion of racial categories has been very complicated. By contrast, the US largely enforced a system of bipolar identity inherited from British colonialism, which then solidified in the late nineteenth century after the Civil War. Nonetheless, race everywhere is socially constructed – for example, it is estimated that nearly half of those who identify in the US as African American have some white ancestors – and in Latin America race is a conflicted category. Many Latin Americans who identify as white, and are seen as white because of their social status, education, and physical features, might not be considered white in the US and vice versa. There are any number of stories of black South American diplomats who were outraged when they encountered discrimination in Washington DC, not because they objected to racial profiling, but because they considered themselves white. It is estimated that of a total population of 522.8 million in the countries of Latin America, a third define themselves as white; a quarter as mestizo (mixed white and Indian); 17 percent as mulatto/Afro-descendant (mixed white and African); about 12 percent as Indian (with Peru and Bolivia as the only countries with a majority Indian population); five percent as black; less than one percent as Asian; and the remaining as other/unknown (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Racial origins of the population of Latin Americans

Source: World Factbook, 2007.

| White | 217 million | 33.3 |

| Mestizo | 165.3 million | 31.3 |

| Mulatto | 90.3 million | 17.3 |

| Indigenous | 60.8 million | 11.6 |

| Black | 24.8 million | 4.7 |

| Asian | 1.4 million | 0.3 |

| Other/Unknown | 6.2 million | 1.2 |

While exact figures are hard to determine, we can draw several conclusions, the most salient of which is that people who are wholly or partially of indigenous, African, and Asian ancestry predominate in Latin America. Certainly no discrimination against a minority should be tolerated anywhere, but in Latin America it bears remembering that the history of discrimination is against the majority population, not the minority. Secondly, whereas indigenous people constitute a minority in most countries, people of whole or partial indigenous ancestry comprise the single largest ethnic/racial group in Latin America as a whole.

Economies

Nature has graced Latin America with stunning natural landmarks, but the gains achieved through human interaction are not all positive since huge numbers of its people are impoverished, while a small group in each country is extremely wealthy. The World Bank calculates that most of the population lacks basic services such as water, sanitation, access to health care and vaccinations, education, and protection from crime. Nearly 25 percent of Latin Americans live on less than US$2.00 a day. Although Bolivia, Colombia, Paraguay, and Chile rank as the countries with the greatest inequality, the sheer numbers of poor in Brazil and in Mexico pose some of the greatest challenges to those nations’ resources. According to United Nations development reports, lack of access to basic infrastructure serves as a major impediment to anti-poverty initiatives throughout the region.

Historians argue over the source of Latin America’s inequality, some tracing it back to the days of European conquest over large indigenous populations and centuries of exploitation of imported African slaves. Others note that Latin American leaders have failed to promote the type of policies for the efficient exploitation of the continent’s vast natural resources that would be required to raise the standard of living of the majority of its people. Another group points to the need to improve Latin America’s commercial relations with the rest of the world, or to build ties among themselves, as through the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which links Canada, the US, and Mexico; the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA); MERCOSUR (called MERCOSUL in English), which includes Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay, and Venezuela; and the Andean Community of Nations (CAN), encompassing Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela. A few nations, especially Chile and Brazil, have pursued bilateral trade agreements with the US, the European Union, and nations in Asia. Similar initiatives by the Peruvian and Panamanian governments to enter into trade pacts with the US have met with stiff opposition from their local labor unions and farmers.

The debates these agreements have generated do not focus on trade per se, but on the long-term impact of entering into compacts with larger, more developed, and technologically more advanced nations. Critics charge that Mexico has benefited little from NAFTA; in fact, NAFTA has resulted in a flood of agricultural commodities into the Mexican market from the US and Canada, where they are produced far more efficiently and cheaply. As a result, Mexican farmers have been driven off the land and into urban squalor, or across the border to the US, in order to survive. Critics of free trade pacts argue that the free flow of capital the agreements nominally protect has proved beneficial only to the rich nations, and perhaps to the wealthy classes of emerging economies. They argue that the pacts have accelerated income inequalities both within Latin America and outside it, in relation to the rest of the world. Contained within the trade debate is the larger issue of neoliberalism, sometimes called the “Washington Consensus,” referring to the push from the United States to keep markets in developing nations open and available for investment and trade agreements favorable to the US. The real impact of foreign investment, and disagreements among and between Latin American governments over the impact of earlier liberal and recent neoliberal policies, is a topic that weaves through this text.

Although critics point to the detrimental impact of free trade deals on agricultural production, especially in Mexico, the fact is that most people throughout Latin America live in cities. By 1960 the majority of the population was involved in nonagricultural production; that is, in the service sector, manufacturing, private and public bureaucracies, and the informal sector. The common assumption is that people making a living in the informal sector – selling what they can on the street, engaged in casual and day labor, or peddling “illegal” wares and services – are very poor. That may be true, with the exception of certain illegal activities such as prostitution, trading in contraband, etc., in which case it is hard to make any overriding assumptions. Yet some entrepreneurs selling homemade crafts, foodstuffs and other objects in local markets earn a very good living – comparable to, or even better than, those employed in manufacturing and the formal economy. The national economy, however, may suffer because of the difficulty of collecting taxes on informal-sector earnings.

A sizeable middle class has emerged in most of the continent’s large cities, concentrated in growing domestic and transnational manufacturing sectors, financial and commercial institutions, government bureaucracies and service sectors, and traditional professional occupations. Probably owing to the precariousness of its position, the middle class has not been a consistently strong voice in the political arena. By the late twentieth century, however, this previously timid group had become a more sustained and consistent actor in many emerging democracies.

Politics

The Latin American political landscape has been as diverse as its geography and culture. Since the end of Spanish and Portuguese colonialism in the nineteenth century, the region has been host to monarchies, local strongman (caudillo) rule, populist regimes, participatory democracy of parliamentary, socialist, and capitalist varieties, military and civilian dictatorships, and bureaucratic one-party states, to name a few. The US has played a strong role, especially during the twentieth century. The lament of Mexico’s autarchic leader, Porfirio Díaz, could be said to be applicable to the continent as a whole: “So far from God, so close to the United States.” British historian Eric Hobsbawm once remarked wryly that Latin America’s proximity to the US has had the effect of it being “less inclined than any other part of the globe to believe that the USA is liked because ‘it does a lot of good round the world.’”1

Latin America’s history is replete with conflict resulting from the unequal distribution of resources among and between nations, classes, racial and ethnic groups, and individuals. In the nineteenth century Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay went to war against Paraguay from 1864 to 1870 in the War of the Triple Alliance. This devastating conflict wiped out half of Paraguay’s population and over 80 percent of its men. The most extensive war, the Mexican Revolution of 1910–21, resulted in the death of an estimated one million people both on and off the battlefield, of a population of 15 million. Other twentieth-century conflicts considered highly costly in terms of human life were the War of the Chaco between Bolivia and Paraguay (1932–5), in which an estimated 150,000 people died, and the civil conflict in Guatemala (1978–96), in which at least 200,000 Guatemalan Indians and mestizos were killed at the direction of a series of brutal military regimes. The country whose history has been most associated with violence is Colombia. From 1948 to 1966 an estimated 200,000–500,000 Colombians (the number varies widely) died in a war between political parties and factions that is known as La Violencia.

One erroneous stereotype, however, depicts Latin America as exceptionally violent, as a place of war, unstable governments, and social strife. In actuality, probably fewer Latin Americans have died as participants in wars and revolutions than is the case in other continents. This is due in large part to the relatively small role Latin American nations played in history’s major international conflagrations, including World Wars I and II and Japan’s war against China (1937–9). Unfortunately, the number of casualties throughout the world has been tremendous: the 20–30 million who died in the Taiping Rebellion in China (1850–64), the massacre of an estimated 1.6 million Armenians in 1915–16, the World War II Holocaust, the Cambodians left to die in the “killing fields” of Pol Pot (1968–87), or the 1994 Rwanda Genocide in which anywhere from 600,000 to one million Tutsis and their Hutu sympathizers were killed in 100 days. The fact that Latin Americans have not historically killed each other in rebellions nor carried out mass slaughters in any greater number than peoples in other parts of the world (and probably fewer) draws into question the cultural stereotyping to which the region has been subjected.

In recent times, progressive and moderate leaders elected to office in many countries of Latin America have attempted to find solutions to the longstanding problems of widespread poverty, malnutrition, lack of education, human rights abuses, and inequality. This political phenomenon, labeled the “Pink Tide,” refers to the election in the last decades of the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries of left and centerleft governments in many Latin American countries, including Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Paraguay, Uruguay, Venezuela, and, disputably, Nicaragua. As opposed to the Cold War label, “the Red Tide,” that implied the spread of communism from the Soviet Union and China to other parts of the world, this “Pink Tide” is a milder, “less Red,” political current. While many of these elected socialist and leftist politicians are sympathetic to their own country’s revolutionary past, have voiced open admiration for Cuba’s stubborn rejection of US hegemony, and have personally suffered under the military dictatorships that dominated much of the region from the 1960s to 1990s, they are at the same tim...