![]()

1

Morphology and Constructive Techniques of Venetian Artilleries in the 16th and 17th Centuries: some notes

Marco Morin

VENETIAN ARTILLERY. – Early guns were of very rude construction. The successive improvements, so for as they can be traced, originated is the north of Italy, and Venice certainly had a large share in bringing them into the practice of war. The brothers Alberghetti, celebrated at first as artists in metal, to whose skill we owe those beautiful fountains in the court of the Ducal Palace which still delight the eye of the traveller, were induced to turn their attention to the casting of guns: and the introduction of boring machines is attributed to them. Leonardo da Vinci also, whose fame as an engineer is less than as a painter only in so far as his works were of a less popular nature, devised several improvements in the manufacture and management of artillery, which were easily reduced to practice by the Venetian workmen; and although he himself does not seem to have been in this immediate service of the Venetian Government still, as his plans became known, and his treatise on gunnery – probably the first scientific work on the subject – was published, he was really and effectively in the service of every Government whose officers had the brains into understand his teachings, or whose workmen had the hands to execute them; in which category the Venetians were pre-eminently included. Toward the end of the sixteenth century they introduced what must be considered as a primitive form of howitzer. for firing grape. It is described by Graziani as a sort of cask of very thick wood. barely a cubit in length, and of about the same bore as a mortar. It must thus have been, inside, about the size of a nine-gallon beer-barrel. This was loaded with leaden balls, and stones as large as an egg. And said to have done good service in into the battle of Lepanto; “on board those ships on which this horrible hail fell it made terrible havoc.” (from Fraser's Magazine as quoted by New York Times, October 31, 1875.)

Introduction

This piece of newspaper writing of about 135 years ago, deal from contemporary routine journalism, nevertheless shows how the importance of Venice in the field of guns and gunnery was, already in the past, widely and popularly perceived. Actually the Serenissima Repubblica, for centuries the most important Italian state and one of the major European countries, invested a huge amount of money and efforts in her heavy armaments and in the production of the necessary gunpowder. Moreover, this example contains a number of errors. In the court of the Ducal Palace there were two wells and not two fountains and the bronze well-heads were cast one by Alfonso Alberghetti and the other one by Niccolo di Conti. Leonardo da Vinci did not devise several improvements in the manufacture and management of artillery, and the primitive form of howitzer for firing grape was not used at Lepanto. We shall leave this catalogue of mistakes to military historians and get back to our main topic.

For the period discussed here, an investigation of the European artilleries reveals a generally notable morphological similarity for which, in absence of writings and/or coats of arms, an origin is not always easily recognisable.

As far as the Venetian pieces are concerned, however, they disclose some distinctive peculiarities that can be of significant help to the underwater archaeologist, especially where bronze cast ordnance is concerned. However, first of all, we must analyze in some detail the various types of artillery in use from the second half the 15th century until the end of the 17th century. A first division can be appreciated between pieces made in iron and pieces made in bronze: the iron ones can be divided into those made by wrought iron and those realized by fusion cast.

Wrought iron is a two-component metal consisting of high purity iron and iron silicate – an inert, non-rusting slag similar to glass. These two materials are merely mixed and not chemically joined as in an alloy. Slag constitutes 1% to 3% and is in the form of small fibres up to 20,000 per inch of cross section. For hammer-welding wrought iron, the technique universally used for large and small pieces, see Smith and R. Rhynas Brown (1989).

Wrought iron is an easy material to work by forging and the best results are obtained at temperatures in the range of 1150 to 1315°C. Wrought iron elements can be welded together without difficulty, always by forging. Structurally, wrought iron is a composite material as the base metal and fibres of slag are in physical association, in dissimilarity to the chemical or alloy relationship that generally exists between the constituents of other metals.

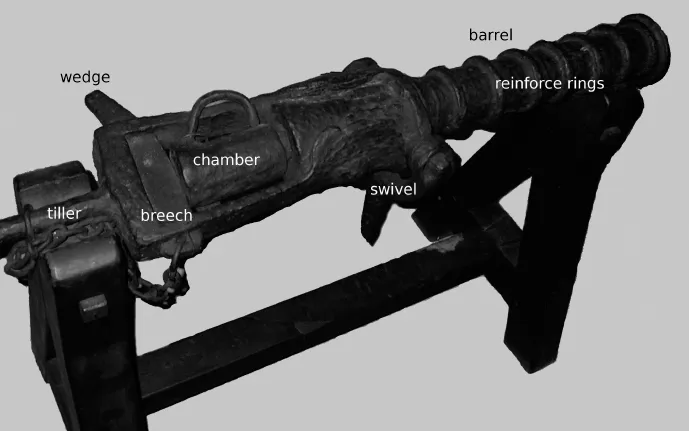

Wrought iron guns were made by the hoop-and-stave method: they were usually breech-loaders, using removable iron chambers with touchholes – containing the gunpowder and closed by wooden wadding. A stone cannonball or scattershot was placed in the barrel. The chamber was locked in place by a wooden wedge, in the bombards placed in wooden carriages or by an iron one in the full metallic pieces (Figure 1.1). These wedges had to be hammered in position in order to force the chamber against the barrel: each weapon was equipped with at least two chambers and so the firing rate was superior in comparison with similar calibre muzzle-loaders. Swivel pieces of this general type were used as railing pieces on large merchantmen and were the basic armament of smaller ones; without significant changes, they were in use for more than three centuries and so their presence alone is not sufficient to date a wreck.

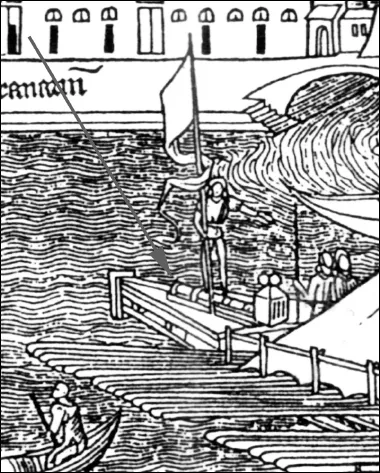

On the main fighting ship of the Mediterranean – the galley – the first gunpowder ordnance mounted was probably a wrought iron breech-loader placed at the stern in wooden balks or in timber beds used to secure the cannon and prevent recoil while firing. Examples of these kinds of artilleries are the iron bombards of the Mary Rose wreck (sunk in 1545) and the ones now in the Tøjhusmuseet in Copenhagen (from the so-called Anholt wreck). Bernhard von Breydenbach, a wealthy canon of the cathedral at Mainz, who journeyed to the Holy Land in 1483–4, compiled the Peregrinatio in Terram Sanctam, a work that was printed in 1486. The book's map of Palestine includes an enlarged illustration of the galley in which he travelled, placed appropriately at the arrival point, the port of Jaffa. Breydenbach was accompanied by Erhard Reuwich, an artist from Utrecht, who is referred to in the text as the author of the map and the six views of Mediterranean towns: Iraklion, Modone, Rhodes and Venice – all of which are folding – as well as the single-page views of Corfu and Parenzo. In the Venice map, a galley with a hooped bombard on the stern can be seen, probably the oldest visual documentation known (Figure 1.2).

In the second half of the 14th century, wrought iron muzzle-loading large bombards were built and employed (in the War of Chioggia), but we do not have positive information on their possible naval utilization.

As far as casting is concerned we know that, in the whole Venetian Terra Ferma, especially in the Brescia (ASV, Senato, Deliberazioni Terra, reg. 4, 46v 28 Luglio 1457) and in the Vicenza territories, medium and small iron muzzle-loading bombards were being produced as early as the latter part of the 15th century (Awty 2007, 788). An extraordinary pattern is provided by a group of 4 practically identical pieces, owned by the Counts da Schio and preserved in their estate of Costozza (Vicenza). These can tentatively be date to 1450–1490 and due to their peculiar morphology that reminds us of the hoop-and-stave arrangement of a cask, only an accurate X-ray investigation has allowed us to establish that this had been realized by casting and not by forging (Figures 1.3–1.4).

To find Venetian cast iron artilleries of large calibre we have to wait until 1690, when in Sarezzo of Val Trompia (Brescia), Tiburzio Bailo began activity as a gunfounder with the help of Sigismondo III Alberghetti, member of the well-known bronze founder dynasty. Sigismondo III, by order of the Venetian Senate, travelled extensively in Europe to study the manufacture of cast iron artillery. In his opinion the best production was English and so, always by order of the Senate, he attended the casting of about 140 pieces of ordnance (cannons and mortars) manufactured in the Weald by Thomas Western for the Republic of Venice. These barrels can be recognised by the presence of St Mark's lion and the initials T W: among them three 18–inch surviving mortars are known in England (Blackmore 1976, 138).

The Bailo production, with the use of iron ore from the Brembana valley (the Val Trompia iron, very good for small arms barrels, was inappropriate for artillery), proved itself of an excellent quality and so, until the death of Bailo in 1708, Venice was able to supply her sail fleet with locally-produced iron artillery. After this, production was resumed by a Carlo Camozio in Clanezzo, north of Bergamo and nearer to the iron mines of the Brembana valley. Soon after another iron cannon-foundry was established at Castro, in the north-west of the Iseo Lake, very near to the south end of the Brembana valley.