![]()

MAPUNGUBWE

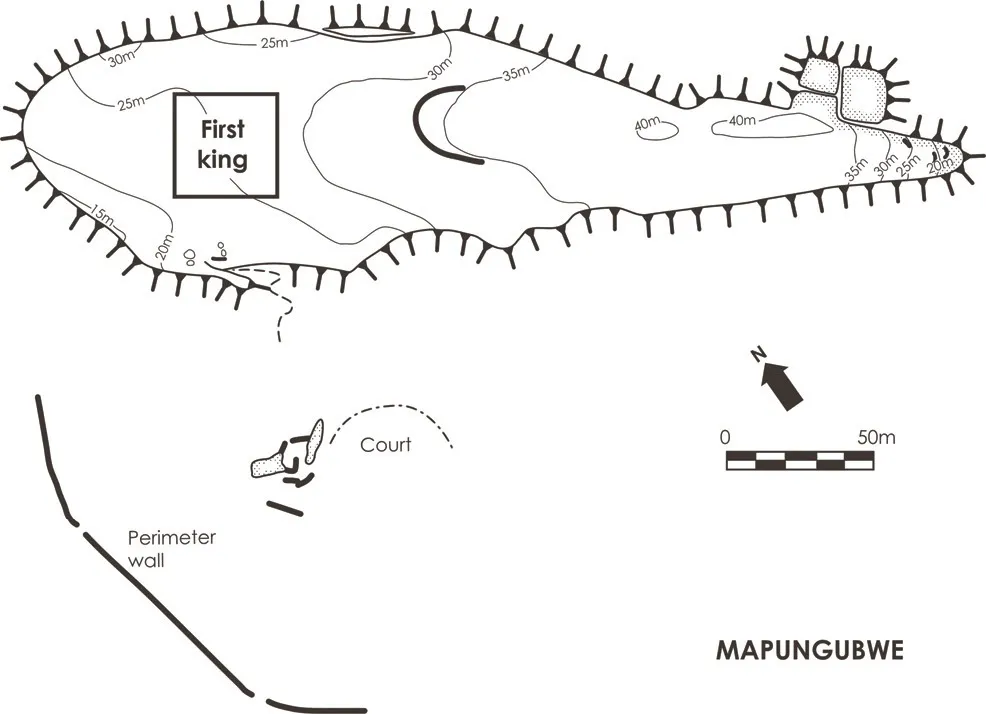

When Mapungubwe became the capital, in about AD 1220, most people settled below the hill and in front of it – that is, on the west side. The commoners’ court was established at the base of the hill next to the tall boulder, and cattle were not associated with it. From the beginning of this new occupation, a few elite people lived on the hilltop.

This is the first time in the prehistory of Southern Africa that a senior leader was so physically separated from his followers. This new spatial pattern is associated with class distinction, and it represents the origins of the Zimbabwe culture.

Until now, Mapungubwe had been a rainmaking hill. By living on top, the leader acquired the power of the place. His new location also emphasised the link between himself, his ancestors and rainmaking. This link is an essential characteristic of sacred leadership.

Southern terrace

The grey soil in front of the hill marks an extensive residential zone. The deep hole, labelled as K8 on the excavation grid, reveals the great depth of the deposit. Excavated in the 1980s, the stratigraphy here has helped to determine the sequence of occupation in the whole site. Zone One, at the bottom, was a sixth-century occupation by Early Iron Age farmers who used Mapungubwe Hill for rainmaking purposes. In Zone Two, AD 1000–1220, when K2 was the capital, some K2 villagers lived at the base of the hill. The relocation of the capital to Mapungubwe occurred in Zone Three, AD 1220–1250. A horizon of burnt huts marks the transition from Zone Two to Three, and it is possible that the people burnt the old village down to start the new capital afresh. Zone Four, AD 1250– 1300, encompasses the decline of Mapungubwe in one interpretation, and its peak in another. This is the subject of on-going research.

Artist’s reconstruction of Mapungubwe town centre

Whatever the interpretation, Mapungubwe was only occupied as the capital for 50–80 years, less than half the duration of K2 – so the great depth of deposit on the Southern Terrace is the result of considerable human activity.

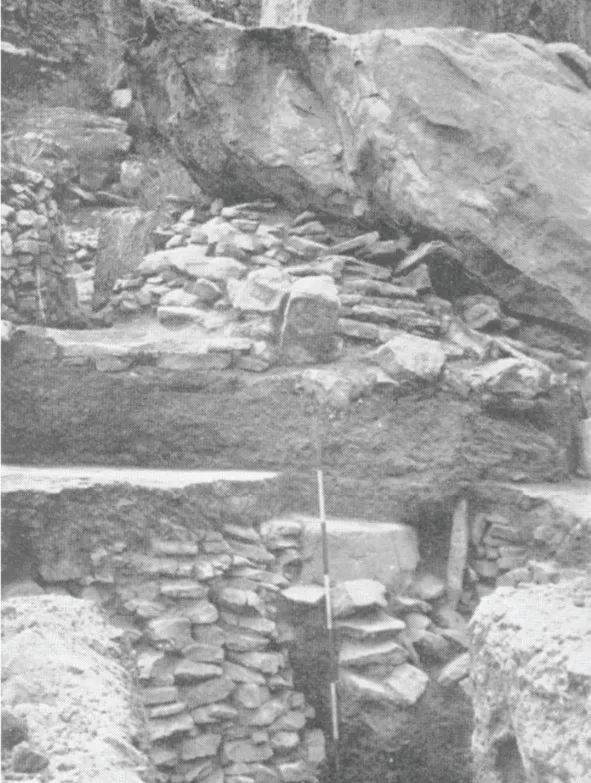

Excavations of square K8, below Mapungubwe Hill. Note the stone foundations of grain bins, one above the other, and the depth of the deposit.

Court officials

Courts belonged to the leader of the settlement, but at Mapungubwe the sacred leader would seldom have been there, because he lived on the hilltop in ritual seclusion. We know from historical examples that a specially designated brother would instead have been in charge. Known as the ‘little father’ in some societies, this brother was the second most powerful man in the capital. This senior man would have had several messengers to summon people for a trial, as well as other officials to help run the court. His office was probably the stonewalled area against the large boulder next to the court. A terrace wall in front probably created a waiting place for people who had come to schedule a court case.

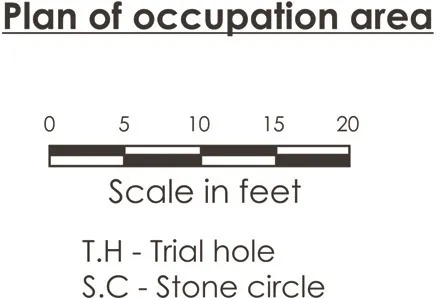

Plan of the office of the ‘little father’ in charge of the court

A 1930s photo shows stonewalling in front of the office. Note how the boulder fell and crushed the steps leading into the office area.

Occupation area

The senior man in charge of the court probably lived with his family in the small residential complex behind the stonewalled office. Excavations in the 1930s uncovered the remains of houses; the largest had been rebuilt at least three times and included a veranda with a small partition wall. The excavators left a witness section to show the successive floors. A small structure nearby may have been a store hut, while small stone circles supported grain bins. A midden full of animal bones still lies in the northern corner.

Plan of the residential area behind the court complex

The old photograph shows successive hut floors in the same area.

Approaches

When Mapungubwe was the capital, there were four stairways up the hill. The main ascent led from the court to the narrow crack in the hillside. Pairs of holes drilled in the rock, underneath the modern ascent, once held poles to help form a stone stairway. Another stone stairway once led up the northern end of the hill. A large block of sandstone has since broken off, but some of the drilled holes are still visible on the remaining rock. A third ascent starts about midway on the west side of the hill. This path connects the hilltop with one of the royal living areas. The final ascent leads up the eastern end of the hill. Stone walls at the top suggest that soldiers guarded this path. In later times, the soldiers were called the ‘eye’ of the king.

Plan of Mapungubwe Hill showing the four main ascents

First king

Clay structures in the first king’s area

The main ascent leads up to the northwestern end of the hill, where excavations in the 1930s and 1980s uncovered a series of house floors. The deepest floor level dates to about AD 1220, and relates to the first sacred leader who lived on Mapungubwe Hill.

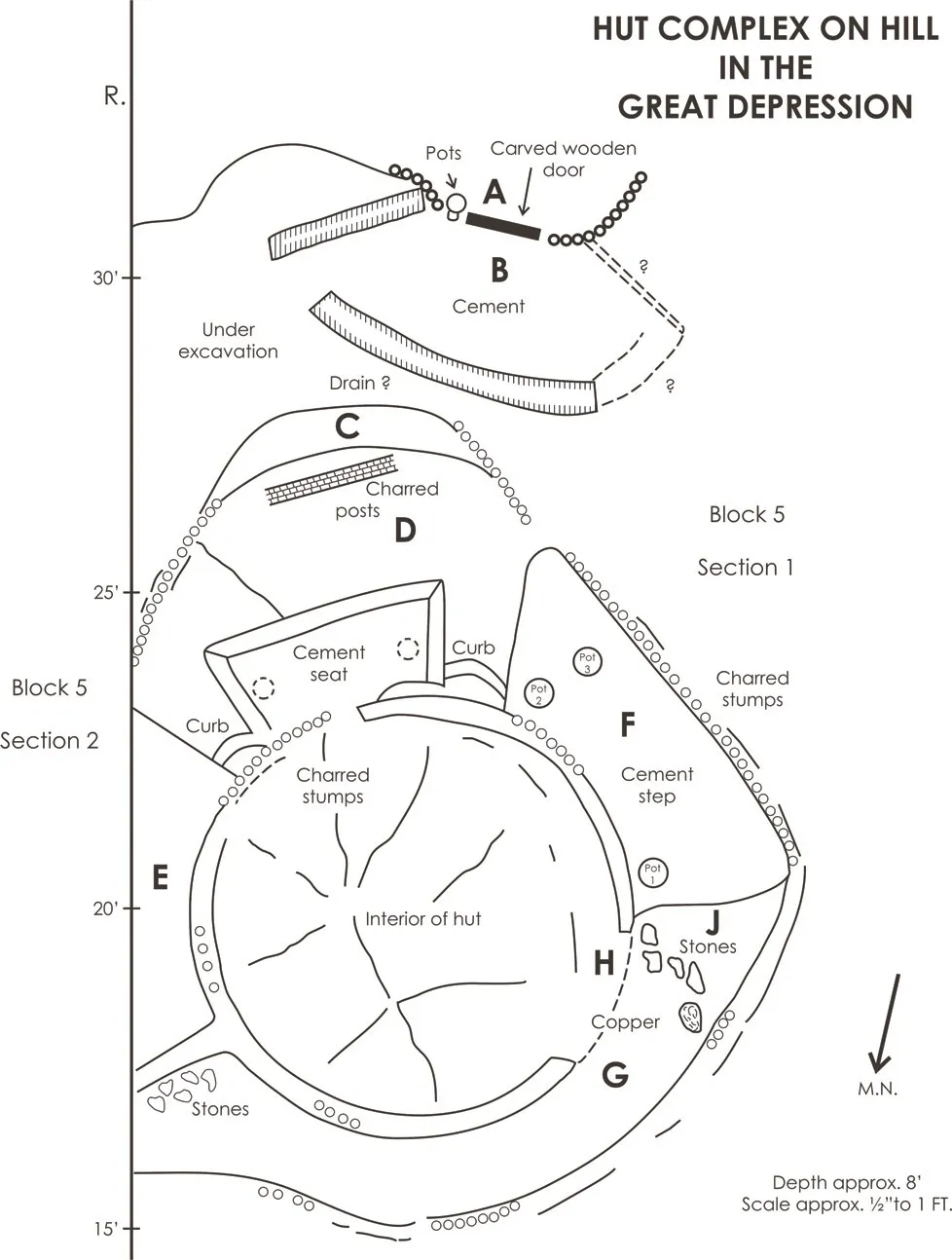

One unusual structure had a wide veranda with two fireplaces (called ‘curbs’) on either side of a seat. The veranda surrounded a small room with a clay floor so hard and well-made that early excavators called it ‘cement’. Another house with the burnt remains of a carved wooden door stood opposite the fireplaces. If these structures followed the later Zimbabwe pattern, then the hut with the door was the king’s own sleeping room, while the king’s special diviner would have used the small hut with the exterior fireplaces. Somewhere nearby would have been an audience chamber where the king received visitors in a formal setting. Finally, the king’s chief messenger would have kept an office towards the front where he could receive the visitors first.

Plan of Mapungubwe Hill showing where the first king lived

Stonewalling

The Zimbabwe culture is internationally known for impressive stonewalling. Few visitors realise, however, that the people at Mapungubwe pioneered the famous walling later used at Great Zimbabwe.

Three walling functions helped to facilitate sacred leadership and class distinction: prestige enclosures, hut terraces, and long boundaries. First an...