Chapter 1

The emotional component of teaching and learning

An introduction to shared meanings

Central to this book is the premise that shared meanings are vital for teaching and learning.

It’s human nature to seek to connect with other people, and shared meanings help us to feel close to others, shape our friendships and give us a sense of connection to the important people in our lives. They also have another function. They are the means by which we transfer information, understandings and skills. They are the vehicle for teaching and learning. As such, they fulfil perhaps our two greatest needs: to connect with others and to learn. Teaching and learning is an attempt to control the generation of shared meanings by introducing a sense of formality, so that the transfer of knowledge and skills is maximised.

There are several features of shared meanings that are important to point out before we examine in greater detail their role in teaching and learning.

We know when shared meanings are being generated

We know what it is to be able to look into someone’s eyes and know that they are connected to us. Sharing the same joke, thought or feeling is a common experience. Equally, we know when someone is not truly attending to us, or when we are trying to get our point across but failing to do so. The children I have worked with are no different in that they seek this connection. Some of them may seek out connection with others in strange ways. Some, for example, seem to feel that their only route is through antagonising others, but the need for connection is still the primary driver for their behaviour.

The ability to connect with others can grow or fade

Many of my pupils had got used to living in a way that does not involve rich connections with other people, and the worry is that this becomes the norm for them as they grow into adulthood. Shaun seemed to be on such a path. When I met him, he was 13, and he seemed determined to go out of his way to be mean and create upset in others. We knew that his home life was chaotic and that he was a product of neglect, so we flooded his life with kindness, and occasionally he showed signs of wanting to interact in positive ways, during which both he and his interlocutors felt happy.

But all our behaviour management techniques failed to work. We put him on internal work experience, for example, helping out in a class of much younger pupils, which he loved. We allowed him to help the school caretaker, because he was good with his hands. We fixed up a range of rewards that really motivated him. Above all, we caught him being good and that changed his image around the school. But our attempts to make him feel valued never really managed to change his image of himself. I did some home visits, only to find that his dad was as immature as him, competing with his son to get my attention, in a way that made it no surprise when Shaun came in the day after and reported that his dad had said I was stupid. It seemed to be part of the family ethos to belittle everyone.

We continued to try to be as positive as possible. Shaun often talked of how thick he was, even though his reading and writing were way ahead of the rest of his class. He often talked about how ugly and fat he was, though he was really quite slim. ‘I’m obeast!’ he would say and there was no gainsaying him. Shaun was negative not just in his talk but in his actions. If he was playing with building bricks, he would get to the point when the bricks he had been putting together risked resembling something – a house, a car or maybe just a wall. The first few times when I made the mistake of commenting that his creation could be something, Shaun would instantly destroy it. Then he internalised this conversation for himself and regularly started to build something, only to rapidly destroy it when any pattern or potential in his creation became apparent.

His classmates hated and feared him. They had no understanding of him beyond his frequent cruelty. They saw his identity as purely negative, despite their incredible levels of tolerance and kindness shown over the years – it was hard for them to see anything else. Whenever there was any interaction in a lesson – such as a debate, a conversation or just a request for a show of hands – Shaun would instantly switch off, and as likely as not disrupt the forum with silly noises or another favourite saying – ‘This is shit!’ – and prepare himself to meet the inevitable challenge from staff with even more obduracy and the closing statement of ‘I don’t care.’

Shaun seemed to be heading for a future with little chance of rich connections with others. When he was 18 and about to leave us, we reminisced about the year in which we first met, when he had often run around the school with two other boys, just for the hell of it. ‘Those days,’ he said, ‘they were the best.’

In the months before he left, he turned his negativity inward. It seemed as though he realised that the process of leaving us meant that we were not a valid repository for all his difficult feelings any more. I worry about Shaun’s future. I hope that he can find the ability to connect with others, and not become someone who floods their interactions with their own thoughts and feelings to the extent that there is no room for those of their interlocutor.

Shared meanings are generated by words plus context

Shared meanings are not the same as words alone. Therefore, they are difficult to control, and can be ephemeral and easily lost. As I said in the introduction, we cannot be sure that the words we say will equate to the meanings generated. Shared meanings are created by more than one person: there is a reciprocity involved, a degree of back and forth. This reciprocity might take the form of a discussion – checking what each other is saying and getting from the interaction – but sometimes it might just be a look.

As such, meanings can change in an instant. You can feel that you are really seeing eye to eye with someone and then an action or word can cause the feeling to evaporate. For example, I once taught a group of lads Romeo and Juliet, and we had lots of fun acting out a fight scene, using the language from the text. It felt like a really successful activity. Then I finished the lesson with some incredibly beautiful music that I felt really captured the tragedy of the story. All the boys just started laughing uncontrollably at what they saw as the dreariness of the singing. I was so disappointed, and not a little embarrassed, because I was so sure that they would see the music in the same way I did. Personal meanings may be relatively straightforward, but shared meanings can easily escape us.

Context can make the meanings of words difficult to control, but it is not as if we use words logically anyway. If you think that words are the tool of perfect logic, spending time with children whose autism has accentuated their sense of literalness will convince you otherwise. For example, Geoffrey, who can forget to think about other people’s feelings when he interacts with them, and so can seem malicious and aggressive. On one occasion, I catch him giving a girl ‘birthday beats’, by which I mean he is punching her on the arm, one punch for each year she is old. I stop him, and he asks why I have done so. I tell him to look at the girl’s face. He sees the tears streaming down and says, ‘Oh, I see what you mean.’

Later I tell him that it upsets me to see him doing unkind things to his friends.

‘Why?’ asks Geoffrey.

‘Well, for one thing I don’t think you really enjoy it overall, because you are always sad about it afterwards, when you realise that your friend is now sad,’ I say. And then I suggest that we should get him back into class so he can apologise to the girl. I start walking but I notice that Geoffrey is not with me. I ask him to come along but he refuses. His shoulders have tensed again. I walk back and say, ‘Geoffrey, come on. Let’s get you back to class.’

‘But I want to know.’

‘You want to know what?’

‘I want to know the other things. You said, “for one thing,” so there must be others. I want to know what they are.’

Shared meanings are at the heart of all we do to help learners

I have worked alongside a range of different play, art and music therapists, psychodynamic therapists, and clinical and educational psychologists. Attuning to the children, understanding how they can collaborate to produce shared meanings, is the goal of all these professionals in their respective roles. Similarly, in school, our approach does not differ if the child is emotionally troubled, if they have autism, severe learning difficulties or a specific learning difficulty, such as ADHD. The physical implementation of the strategies may differ, but the aims in each case are the same: maximise the shared meaning between the child and the people around them.

Shared meanings, the emotions and teaching and learning

I’ll now try to explain the process of teaching and learning to show the centrality of shared meanings, and the role of the emotions too. Let us start with the idea that the interaction between the teacher and learner is simply academic, cognitive or rational. Even within these narrow parameters, which ignore the richness of most human interactions, the idea of shared meaning is key because at the heart of the teaching and learning process is the point at which the teacher meets the learner, and at which their two minds overlap.

This overlap is crucial, and teachers work hard to shape how it happens. Simply put, if the teacher’s talk is too complex – beyond the learner’s current level of understanding of a topic – it is going to make no sense to the learner, who will therefore not learn anything. If the teacher makes things too easy, then the meaning that the teacher and learner make together will not extend the learner or introduce them to new ways of understanding. So it is important that the teacher accurately assesses the learner’s current levels of understanding, so that they can pitch the complexity of the lesson just ahead of that understanding. Once the teacher can structure this new meaning in such a way that the learner can make sense of it for themselves, the learner’s understanding is taken forward. This is Vygotsky’s zone of proximal development.

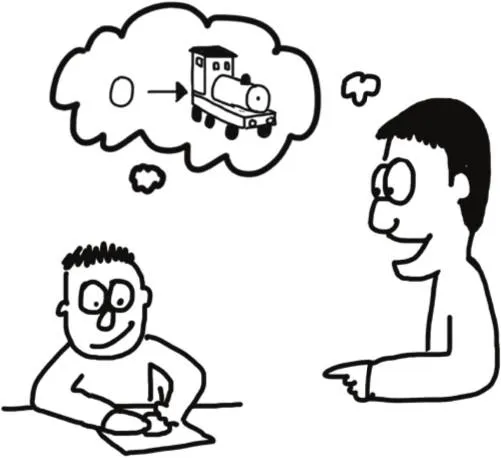

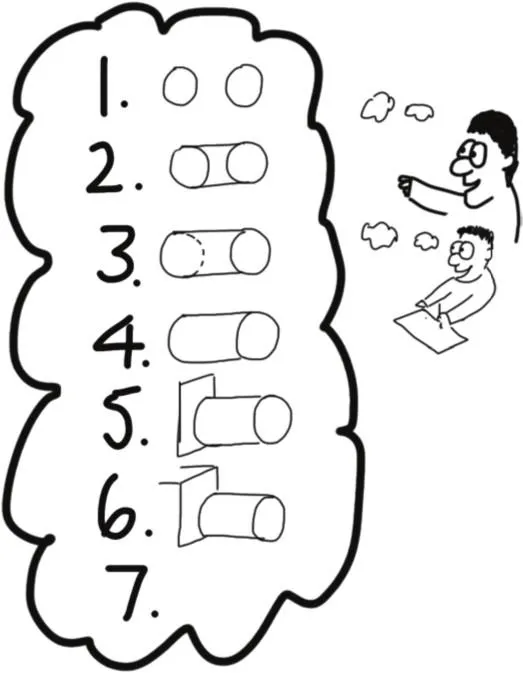

In the simple example below, in an art lesson, the teacher sees that the learner can draw circles.

The teacher thinks that he can extend the learner’s drawing skills. Perhaps he knows that the learner likes trains, and so uses that as motivation (although talk of motivation is letting the emotions creep into our example a little, of course). ‘Hey,’ says the teacher, ‘if you know how to draw a reasonably accurate circle, I can show you how to draw a train.’

‘Okay,’ the pupil says, and has a go at following the teacher’s demonstration but struggles.

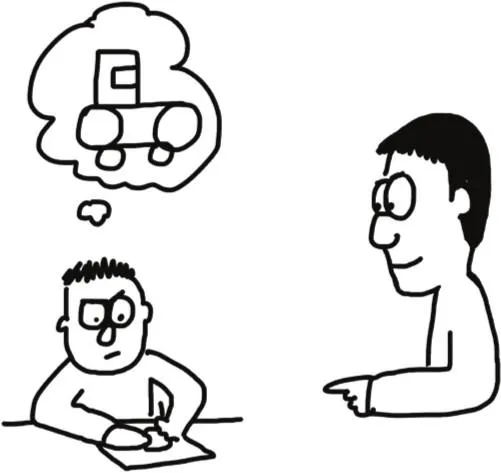

So the teacher, refining his understanding of the learner’s ability, decides to make the instructions more easily understandable for the pupil. He breaks them down into steps and provides a commentary to help the learner think the steps through.

‘Step one is to draw a circle. Then draw another one of the same size. Then draw two lines connecting the circles. Next, rub out one part of one circle, and then you have a cylinder.’

The teacher can see that they are both on the same page in their thinking now. There is a perfect match between the two of them, a reciprocity in their understanding. With the teacher’s guidance, the pupil can do something he has never been able to do before, i.e. begin to draw a train.

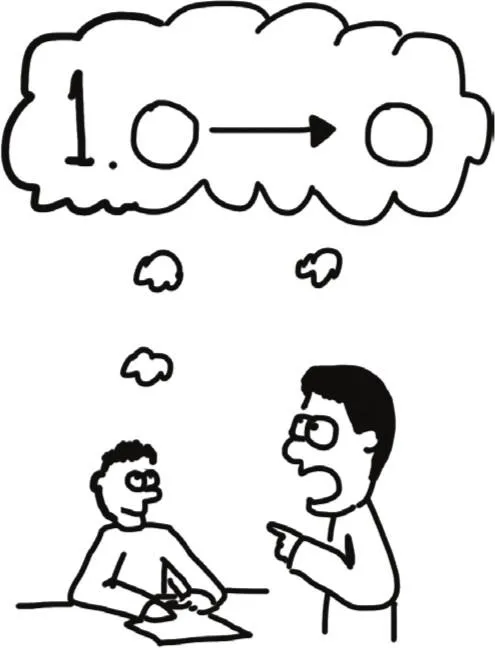

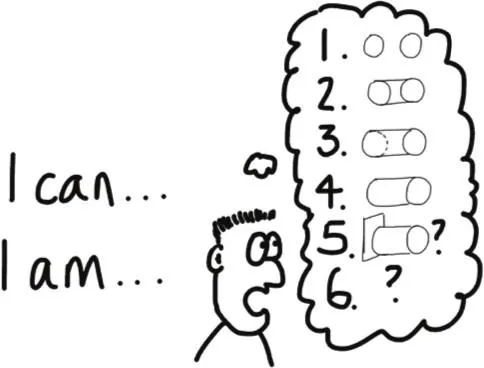

Then the teacher goes away. The pupil is left to go through the steps on his own. He remembers the way that the teacher talked the problem through, and showed him how to break it down into steps. He remembers what to focus his attention on, and the script needed to get him started. Perhaps the learner repeats the conversation that he had with the teacher, but on his own this time. It might help to say it out loud at first, so that he can use his auditory memory to help his cognition. He might say something like, ‘So we start by drawing a cylinder, which is just two similar-sized circles connected by straight lines. And then I have to rub something out? Oh yes, I remember.’

In this case, the learner has internalised the dialogue between himself and the teacher for the first four steps only. He can’t quite get the fifth or sixth step, so he will need some more help from the teacher; they will have to create the shared meaning again to support the learner’s internal monologue until he can appropriate all the steps for himself. But that’s okay, practice makes perfect. Because the dialogue was at the right level, the learner was able to take quite a lot of it on board and make it his own: part of his own internal monologue that he refers to when he thinks about how to do this activity. In other words, there was quite a lot of shared meaning between the teacher and the learner, which meant that the learner could understand a new concept and, therefore, learn. In Vygotskian theory, this is development proceeding from the intermental to the intramental, from dialogue to internal monologue.

To have a teacher who seems to know where the limits of your understanding lie, accepts you for who you are, and is able to understand the way in which you can be successfully led to new understandings is a powerful thing to experience. It gives a feeling of connection and intimacy. It’s an amazing feeling to have someone who understands you and can get inside your head with just the right thing to say. As adults we may avoid situations like that because we may not like to feel that vulnerable, but many of us will remember having teachers at school who did that for us.

The shared meaning is the vehicle for new understanding. In my own career, I started off by making assumptions about my pupils, which meant that I made mistakes at step one of this process: I failed to make an accurate assessment of what my pupils did and did not understand. I thought that they would know, for example, what a map of the world looks like. I thought that they would be able to read basic words. I thought that if I told them three instructions, they would be able to follow all of them. Then I revised my assessment to two instructions, and then one, and then I realised that it was not the instructions that were the problem, but my ex...