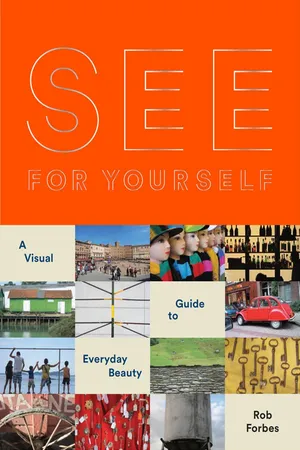

![]()

FACTORY FLOORS,

BUMPY STREETS

& FOOD CARTS

ROME

left top

WARREN

right top

NAPLES

WATERSHED

bottom

SAN FRANCISCO

ONE TERRIFIC THING about seeing for yourself: You don’t have to go far to do it. The obvious place to start looking for stuff is right under your nose. There is probably an interesting composition to be found around you wherever you are reading this book. You can make an interesting composition out of almost anything if you play around a little and see it from a fresh perspective.

But the reality is we often find inspiration, and take more time to look at things, when we step outside our daily routines. Travel opens our eyes, and the inspiration for this book began as I traveled abroad. It led me to ponder why I was so alert to details in Italy yet so indifferent to them back home in San Francisco. I began an exercise of more mindful observation of my immediate surroundings. We travel for a number of reasons; we come back, as they say, with stories to tell but also with a fresh perspective on where we live.

MARKETS, PORTS, FACTORIES, STUDIOS

My favorite haunts and my most reliable sources for inspiration are primarily urban. Within that context, I seek out places where we are not being directed to what to see, or being manipulated and told what to buy. (This may strike many readers as surprising, given my own work in creating marketplaces for selling designed goods and products for our lives.) Many of my images come from workplaces: commercial kitchens, toolsheds, artists’ and designers’ studios, ports, ranches, and factory floors. These are all places where things are produced rather than sold. The human love and need for making things has been a personal inspiration to me, dating back to childhood and then ten years producing ceramics.

Images taken from a road trip through Maine one summer help illustrate my point. If you view Maine from a car traveling on main roads in summer, it feels like one big tag sale and discount shopping mall. The signage itself is more curious and amusing than the products being sold. But take a detour and head toward working harbors and docks, and you’ll soon see stacked, graying lobster crates, red-and-white tattered buoys, tangled fishing gear, sea-battered boats, and other unaffected examples of human engineering and purpose. Maine corners the market on quaint small towns, and we find predictable artwork being sold along Main Streets, items made as mementos to feed a tourist trade. So get into the abundant nearby artists’ studios and see this: The way brushes and tools are arranged gives us as much insight into the artist’s thinking as his or her artwork. What we do unconsciously is more revealing than what we do consciously. In this case the human need for order, to get work done, to fuel a need to make, is both honest and elegant.

Factory floors often make for studies in materials, patterns, and shapes. Again, how something is made—the series of gestures and materials—is often more interesting to me than the final object or good with its intended use. I equate this with how many of us prefer dining at a restaurant counter, watching the line cook move through a specific choreography with ingredients, tools, and flame, rather than sitting at a table awaiting the final dish. I take every opportunity to visit artists and designers in their studios and chefs in their kitchens—just to see stuff they have around, in what form, and how it is arranged.

Live and spontaneous markets and shops are particularly compelling for many of us—it’s no wonder we see so much activity in so many American cities these days: street vendors, food trucks, local farmers, flea and fish markets, cafés, roadside stands. Places run by people who know and love what they sell. (As opposed to chain stores managed by marketing managers who prioritize products on the shelves based first on profit margins and staffed by employees clocking time.) In farmers’ markets, owners stack and arrange their goods without the need to shroud it in commercial packaging. We see and feel integrity and simplicity at work, and a direct hand involved. As humans, we are traders and barterers, and this direct encounter with makers reminds us of this honest social need.

Farmers’ markets have been growing at a faster pace than malls in the last decade, in blue and red states alike. We all love them. Perhaps this is because the stacked fruit and vegetables remind us that we are, and always have been, gatherers. Or perhaps the patterns and repetition of these foodstuffs are lodged somewhere in our deep subconscious as substances of survival. We equate them with all that is good: contentment, serenity, and feeling our place in the world.

CITIES

Most of the photos in this book are taken from the streets of cities. So, why is that? Cities are the best places for the obvious reason that they have a lot more streets and sidewalks, but they also have greater density of everything: people, buildings, history, products, stores, signs, and all the other details that combine to make up texture.

They are where most of us spend most of our time, in ever-increasing numbers. (The year 2012 marked the first time in human history that more people lived in cities than not.) More is at stake for us in our cities: They simply mean more to more people than other places. They are the repository and centers of our culture. Many cities have been under siege from the forces of shortsighted modern commercial development, and in particular the automobile, over the last fifty years, so they deserve a special focus today. The greater awareness we have toward our cities, the more likely we will be to preserve their assets.

Almost any town or city will have an abundance of subjects for visual study, and there are photos from more than a hundred cities or towns in this book. I’ve made examples of three of my favorite cities, each with unique history and circumstances that made them special: Charleston, South Carolina; Cartagena, Colombia; and Amsterdam, Netherlands. As diverse as these cities are, they share one common trait: They are extremely pedestrian friendly, that is, walkable. And none of these examples came to be pedestrian friendly by chance, but rather by unique forces that allowed them to preserve their identity. In these cases the forces were, respectively, a mayor, an international organization, and a public protest.

top

NAPLES

left bottom

DEER ISLAND

right bottom

VINEYARD HAVEN

left

CHARLESTON

Charleston, South Carolina

The more walkable U.S. cities, such as New York, Chicago, and San Francisco, are a lot more conducive to seeing than those cities that were designed around the car, such as Houston, Atlanta, and Los Angeles, where walking is not given much of a chance. And one smaller U.S. city holds its own against the bigger metropolises: Charleston, South Carolina. Walk this city (with a modest population of 120,000), and you will find more diversity in architecture and cultural history and texture than you will in many much larger cities. How did this happen? Simple. The roads were not widened to make it easy for cars to speed through, parking lots did not take up precious public space, and shortsighted developers were prevented from replacing older, historic buildings. The shortsighted commercial interests have been kept at bay by the visionary mayor, Joe Riley, an eight-term politician who has battled to keep the city safe and sane for residents, not cars, for four decades.

And all across America the same phenomenon can be seen: a visionary mayor taking a stand for public spaces and residents over the need to move cars in and out of the city and thoughtless development. It has been through the force of their will and political power that we now have world-class destinations such as Millennium Park in Chicago (Mayor Richard Daley); and a rehabilitated Times Square, High Line, and neighborhood amenities such as bike lanes in New York (Mayor Michael Bloomberg). An outstanding example of this in San Francisco was Mayor Art Agnos’s decision to block the rebuilding of the Embarcadero Freeway following the Loma Prieta earthquake in 1989. The east-facing waterfront has become one of the most valuable amenities in the city, thanks to a mayor with vision and conviction. (He lost th...