eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

Art Made from Books

Altered, Sculpted, Carved, Transformed

This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

About this book

Artists around the world have lately been turning to their bookshelves for more than just a good read, opting to cut, paint, carve, stitch or otherwise transform the printed page into whole new beautiful, thought-provoking works of art. Art Made from Books is the definitive guide to this compelling art form, showcasing groundbreaking work by today's most showstopping practitioners. From Su Blackwell's whimsical pop-up landscapes to the stacked-book sculptures of Kylie Stillman, each portfolio celebrates the incredible creative diversity of the medium. A preface by pioneering artist Brian Dettmer and an introduction by design critic Alyson Kuhn round out the collection.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Art Made from Books by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

INTRODUCTION

ALYSON KUHN

I Su Blackwell, The Book of the Lost, 2011. Secondhand book, lights, glass, wood box.

This anthology showcases the work of artists whose primary material is books. These artists do not make books; rather, they take books apart. Interestingly, a standard nomenclature for this relatively recent art form has yet to emerge. The term “altered books” is widely used by artists and curators, but many members of the art-appreciating public find it misleading. Doug Beube, who has been altering books for more than thirty years, likes the word bookwork, which is logical and evocative. Beube sees himself as a sculptor who manipulates books, and he uses the term mixed media artist because he also employs collage, installation, and photography. Both Beube and Brian Dettmer, who contributed the preface to this anthology, have pioneered techniques that continue to inspire a new generation of book artists.

Jewelry-maker best describes what Jeremy May does. He crafts rings, bracelets, and necklaces by laminating many, many layers of paper that he cuts with a scalpel from the pages of a single book. Jennifer Collier stitches pages from vintage storybooks, cookbooks, and instructional manuals to fashion her pieces—clothes, shoes, and household objects. In May’s work, the original text is obscured; in Collier’s, the original narrative literally provides the fabric. Other artists employ, and sometimes combine, elements of origami and paper cutting.

Suffice it to say, the works assembled here are remarkably diverse in form, size, and scale. May’s “literary jewelry” and Arián Dylan’s paperback chess set are at the diminutive end, whereas Pamela Paulsrud’s Bibliophilism turns the spines of several hundred discarded books into a huge area rug, and Yvette Hawkins’s installations of cylindrical books fill an entire gallery. In between are Vita Wells’s airborne cluster of individual volumes, and encyclopedic multivolume landscapes by Guy Laramée and Brian Dettmer.

The artistic alteration of books got its start, with a bang, in the late 1960s. British artist Tom Phillips set himself the challenge of buying a used book and altering every page of it by painting, collaging, or cutting. The novel he purchased was A Human Document by Victorian author William Hurrell Mallock. Phillips named his own work A Humument: A Treated Victorian Novel. Phillips celebrated his seventy-fifth birthday in 2012, coincident with the publication of the fifth revised edition of A Humument. Phillips continues to revise his opus, and to share the work in its entirety on the project’s official website (www.humument.com). Phillips has further embraced new technology: a Humument app for iPad is now available.

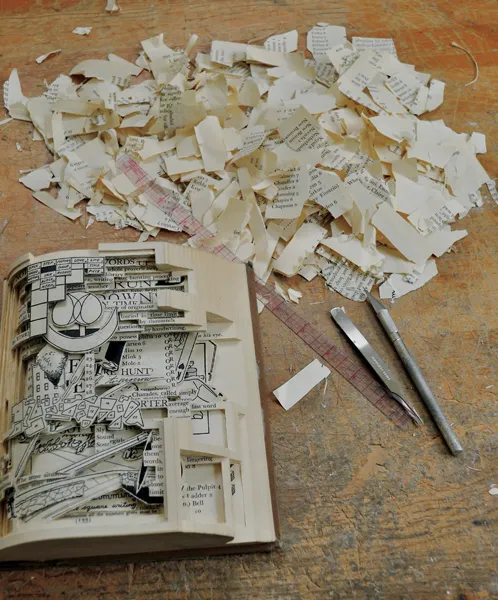

II Brian Dettmer, process shot.

The notion of “treating” a book in this way has historical precedent, albeit more about collecting and less about creating than Phillips’s undertaking. Back in eighteenth-century England, the practice of extra-illustration became fashionable. As its name suggests, this involved adding illustrations and news clippings from other sources, usually to a biography. So, the original bound text was supplemented by the owner, who then possessed a uniquely curated edition—an interesting variation on vanity publishing. For a time, publishers actually included blank pages to accommodate such additions; with other books, an owner would have the original volume unbound and then rebound. The Biographical History of England (1769) by the Reverend James Granger was so popular with extra-illustrators that this practice became known as grangerism.

III Brian Dettmer’s collection of used X-Acto blades.

Today, reference books that have outlived their usefulness as sources of information are treasure troves for contemporary book-altering artists. Volumes with patterned, stamped, or otherwise embellished covers also have potential. Occasionally, a self-help book, a telephone directory, or a scientific report may become fodder for a bookwork. Some book lovers are uncomfortable with the notion of altering books to make art. We are taught as children to respect books, to treat them with care. Yet, many of us find their contents so personally meaningful that we write notes in the margins or even highlight entire passages. We may dog-ear the pages of a paperback to mark our place. Author Anne Fadiman, in her essay “Never Do That to a Book” (from Ex Libris: Confessions of a Common Reader), divides book lovers into two categories, the “courtly” and the “carnal.” The courtiers, if you will, treat books as sacred objects; the carnal readers make notes in, and take other liberties with, their books. Both groups love their books, but show it differently.

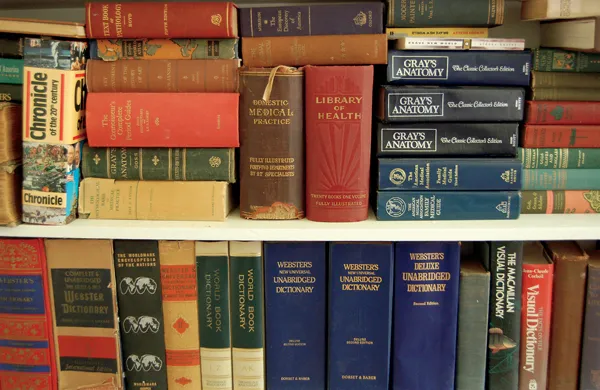

IV Two of the many bookshelves in Brian Dettmer’s studio.

Altered books tap into our collective heightened interest in books as objects. Physical books, as differentiated from digital versions, tend to trigger memories, both visual and tactile. Our eyes read a book, our hands feel it and hold it, and our muscle memory deepens our relationship with it. Some readers keep the receipt for a book right inside the front cover, especially if it was purchased on a trip. Many shops automatically slip their bookmark into a book. Handheld embossers, bookplates, and rubber stamps are all popular ways to identify your book as yours.

Then, when we are finished reading a book, we decide whether to keep it or lend it or re-gift it. We may take it to a used bookstore, or sell it online, or donate it to a library sale—where book-altering artists find their raw materials, and give them new life.

Imagine that you are an author, and one day you receive as a gift a copy of your first novel, but it has been physically altered to the point where it is no longer possible to actually read the story. This happened to writer Jonathan Lethem several years ago. The book was Gun, With Occasional Music, and it had been cut into the shape of a pistol by artist Robert The, whose work Lethem describes as “the reincarnation of everyday materials.” The writer reflects on this “strange beauty of second use” in an article published in Harper’s Magazine in 2007, concluding “the world makes room for both my novel and Robert The’s gun-book. There’s no need to choose between the two.” The artist has made other gun-books, including one from The Medium is the Massage by Marshall McLuhan and Quentin Fiore (p. 164).

V Guy Laramée using a sandblasting cabinet to contain the dust.

VI Jeremy May’s sander bits for his rotary tool.

VII Lisa Kokin’s sewing machine.

More and more art galleries have begun to show altered books. One gallerist who has featured these works, both in an annual Art of the Book exhibition and in the occasional solo show, is Donna Seager of Seager Gray Gallery. She feels these works evoke, first and foremost, surprise—and then curiosity and delight.

A book is a highly familiar and beloved form. When it is altered, so many associations are called into play, including the deep relationship we have with books in general and with certain books in particular Some people’s initial reaction is horror at the evisceration of a sacred or precious object, but then the fertile field that a book can be as material for art becomes evident. Content andform—and our attitudes or perceptions—are manipulated at the same time. The work engages not only the eye, but also the intellect, allowing for powerful commentary in concert with extraordinary visual appeal.

In the summer of 2012, the Christopher Henry Gallery in New York mounted an international exhibition titled A Cut Above: 12 Paper Masters. Four artists whose work appears in this book were included in that show: Doug Beube, Brian Dettmer, Guy Laramée, and Pablo Lehmann. Through spending time with their work, co-curator Diana Ewer observed that by transforming a book into a sculpture, the artist in a sense permits the book an alter-ego.

These artists turn books into new objects within their own right, 2-D and 3-D sculptural works that evoke a visual pleasure and also challenge our own understanding of what a book has been and what it should be. The artists play on our familiar experience of the book, turning it on its head by cutting, sawing, shredding, and stitching specific books remembered from childhood as sacred cultural artifacts! We are engaging with something that is intellectual and to an extent political. These artists are agents of change, inviting us to confront and question how we understand and process knowledge. Whilst we continue to remain aware of books’ original purpose—bookworks have an immediate poignancy as the Internet surpasses printed material as our primary focus for obtaining information and, for many people, seeking entertainment.

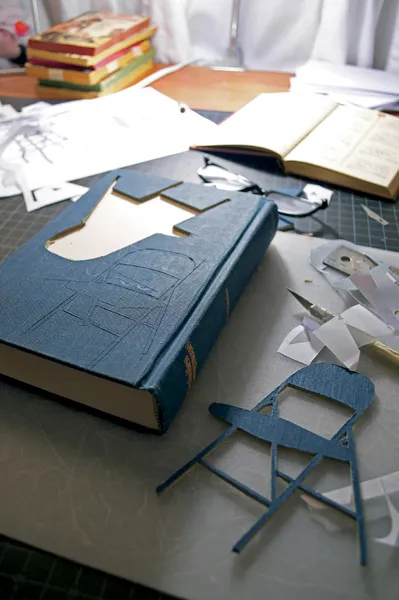

VIII Thomas Allen, process shot.

IX Jennifer Collier finishing a pair of shoes.

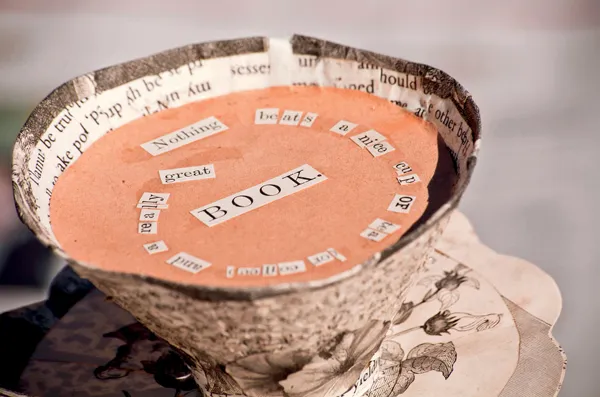

X

XI

X, XI Anonymous, @edbookfest (6/10), 2011.

This was made for the Edinburgh International Book Festival. Really, is there anything nicer than a cup of tea, a cake, and a lazy afternoon with a book?—Anonymous

XII Anonymous at work in her studio.

This anthology includes an anonymous artist, someone who has chosen to receive no personal recognition or compensation for the ten bookworks she made (she has revealed herself to be female) and mysteriously left at libraries and other cultural centers throughout Edinburgh in the course of 2011. The pieces share a sense of creative abandon or frenzy or tatter—as if they have weathered a storm or a tempest in a Mad Hatter’s teapot. They have been w...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- James Allen

- Thomas Allen

- Noriko Ambe

- Anonymous

- Cara Barer

- Doug Beube

- Su Blackwell

- Jennifer Collier

- Brian Dettmer

- Arián Dylan

- Yvette Hawkins

- Nicholas Jones

- Jennifer Khoshbin

- Lisa Kokin

- Guy Laramée

- Pablo Lehmann

- Jeremy May

- Pamela Paulsrud

- Susan Porteous

- Alex Queral

- Jacqueline Rush Lee

- Georgia Russell

- Mike Stilkey

- Kylie Stillman

- Julia Strand

- Robert The

- Vita Wells

- Artist Bios

- Image Credits