![]()

THE SUFFRAGETTE

CHAPTER I

EARLY DAYS

FROM THE FORMATION OF THE WOMEN’S SOCIAL AND POLITICAL UNION TO THE SUMMER OF 1905.

FROM her girlhood my mother, the founder of the Women’s Social and Political Union, had been inspired by stories of the early reform movements, and even before this, at an age when most children have scarcely learnt their alphabet, her father, Robert Goulden, of Manchester, set her to read his newspaper to him at breakfast and thus awakened her lasting interest in politics.

The Franco-German War was still a much-discussed event when Robert Goulden took his thirteen-year-old daughter to school in Paris, placing her at the Ecole Normale, where she became the room-companion of Henri Rochfort’s daughter, Noémie. Noèmie Rochfort told her little English schoolfellow much of her own father’s adventurous career, and Emmeline Goulden soon became an ardent and enthusiastic republican. She was now delighted to discover that she had been born on the anniversary of the destruction of the Bastille and was proud to tell her friend that her own grandmother had been an earnest politician, and one of the earliest members of the Anti-Corn Law League, and that her grandfather had narrowly escaped death upon the field of Peterloo. Even before her school days in Paris she had been taken by her mother to a Women’s Suffrage meeting addressed by Miss Lydia Becker.

On returning home to England, Emmeline Goulden settled down at seventeen years of age to help her mother in the care of her eight younger brothers and sisters, and when she was twenty-one she married Dr. Richard Marsden Pankhurst, who was many years older than herself, and had long been well known as a public man.

Dr. Pankhurst had been one of the founders of the pioneer Manchester Women’s Suffrage Committee and one of its most active workers in the early days. He had drafted the original Women’s Enfranchisement Bill, then called the Women’s Disabilities Removal Bill, to give votes to women on the same terms as men, which had first been introduced by Mr. Jacob Bright in 1870 and had then passed its Second Reading in the House of Commons by a majority of thirty-three. With Lord Coleridge, Dr. Pankhurst had acted as counsel for the women who had claimed to be put upon the Parliamentary Register in the case of Chorlton v. Lings in 1868. He was also at the time one of the most prominent members of the Married Women’s Property Committee and had drafted the Bill to give married women the absolute right to their own property and to sue and be sued in the Courts of Law, which was so soon to be placed as an Act upon the Statute Book. Two years before this great Act became law, Mrs. Pankhurst was elected to the Married Women’s Property Committee, and at the same time she became a member of the Manchester Women’s Suffrage Committee.

In 1889 my parents helped to form the Women’s Franchise League. My sister Christabel and I, then nine and seven years old, already took a lively interest in all the proceedings, and tried as hard as we could to make ourselves useful, writing out notices in big, uncertain letters and distributing leaflets to the guests at a three days’ Conference held in our own home. About this time we two children had begun to attend Women’s Suffrage and other public meetings, and these we reported in a little manuscript magazine, which we both wrote and illustrated. When some few years afterwards, owing chiefly to lack of funds and the ill health of its most prominent workers, the Women’s Franchise League was discontinued, Dr. and Mrs. Pankhurst returned to Manchester and worked mainly for general questions of social reform. Years before, my mother had joined the Women’s Liberal Federation in the hope that it would work to remove both the political and economic grievances of women and to raise the status of women generally, but finding that the Federation was being used merely to forward the interests of the Liberal Party, of which women could not be members and in the formation of whose programme they were allowed no voice, she had resigned her membership. In 1894 she and Dr. Pankhurst joined the Independent Labour Party, one of the decisive reasons for this step being that, unlike the Liberal and Conservative parties, the Independent Labour Party admitted men and women to membership on equal terms. In the same year Mrs. Pankhurst was elected to the Chorlton Board of Guardians, and remained a member of that body for four years. This experience taught her much of the pressing needs of the poor, and of the bitter hardships, especially, of the women’s lives.

After Dr. Pankhurst’s death, in 1898, Mrs. Pankhurst retired from the Board of Guardians and became a Registrar of Births and Deaths.

For the next few years, my mother took no active part in politics, except as a member of the Manchester School Board,1 but in 1901 my sister Christabel became greatly interested in the Suffrage propaganda organised by Miss Esther Roper, Miss Eva Gore-Booth, and Mrs. Sarah Dickinson amongst the women textile workers. She was also elected to the Manchester Women’s Suffrage Committee, of which Miss Roper was Secretary. Christabel soon struck out a new line for herself. Impressed by the growing strength of the Labour Movement she began to see the necessity of converting to the question of Women’s Suffrage the various Trade Union organisations, which were upon the eve of becoming a concrete force in politics. She therefore made it her business to address as many of the Trade Unions as were willing to receive her.

We were all much interested in Christabel’s work and my mother’s enthusiasm was quickly re-awakened. The experiences of her later years had brought her a keener insight into the results of the political disabilities of women, against which she had rebelled as a high-spirited girl, and she now realised more strongly than ever before, the urgent and immediate need for the enfranchisement of her sex. She became filled with the consciousness that her duty lay in forcing this one question into the forefront of practical politics, even if in so doing she should find it necessary to give up all her other work. The Women’s Suffrage cause, and the various ways in which to further its interests were now constantly present in all our minds. A glance at the early history of the movement, to say nothing of personal experience, was enough to show that the Liberal and Conservative parties had no intention of taking the question up, and, after mature consideration, my mother at last decided that a separate women’s organisation must be formed. Therefore, on October 10, 1903, she invited a number of women to meet at our home, 62 Nelson Street, Manchester, and the Women’s Social and Political Union was formed. Almost all the women who were present on that original occasion were working-women, Members of the Labour Movement, but it was decided from the first that the Union should be entirely independent of Class and Party.

The phrase “Votes for Women” was now for the first time in the history of the movement adopted as a watchword by the new Union. The propaganda work was at first mainly carried on amongst the women workers of Lancashire and Yorkshire and, in the Spring of 1904, as a result of the Women’s Social and Political Union’s activities, the Annual Conference of the Independent Labour Party instructed its Administrative Council to prepare a Bill for the Enfranchisement of Women to be laid before Parliament in the forthcoming session. This Resolution, though carried by an overwhelming majority, had been bitterly opposed by a minority of the Conference, who asserted that the Labour Party should not concern itself with a partial measure of enfranchisement, but should work directly to secure universal adult suffrage for both men and women.

Therefore, before preparing any special measure, the National Administrative Council of the Independent Labour Party went very carefully into the whole question. They were advised by Mr. Keir Hardie and others who understood Parliamentary procedure that a measure for universal adult suffrage, which would not only bring about most sweeping changes, but would open countless avenues for discussion and consequent obstruction, could never hope to be carried through Parliament except by the responsible Government of the day. It was, therefore, useless for the Labour representatives to attempt to introduce such a measure. In addition to this, it was pointed out that, whilst a large majority of the Members of the House of Commons had already pledged themselves to support an equal Bill to give votes to women on the same terms as men, no substantial measure of Parliamentary support had as yet been obtained for adult suffrage, even if confined to men. Taking into consideration also the present state of both public and Parliamentary feeling and with a million more women than men in the British Isles, there was absolutely no chance of carrying into law any proposal to give a vote to every grown man and woman in the country. Having thus arrived at the conclusion that an adult suffrage measure was out of the question, the Council now carefully inquired into the various classes of women who were possessed of the qualifications which would have entitled them to vote had they been men. On its being ascertained that the majority would be householders, whose names were already upon the register of Municipal voters, the following circular was addressed to all the Independent Labour Party branches.

We address to your branch a very urgent request to ascertain from your local voting register the following particulars: —

(1)The total number of electors in the Ward.

(2)The total number of women voters.

(3)The number of women voters of the working classes.

(4)The number of voters not of the working classes.

It is impossible to lay down a strict definition of the term “working classes,” but for this purpose it will be sufficient to regard as working-class women, those who work for wages, who are domestically employed, or who are supported by the earnings of wage-earning children.

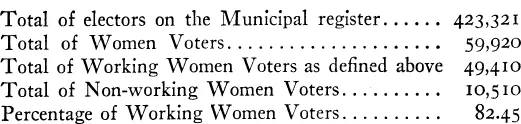

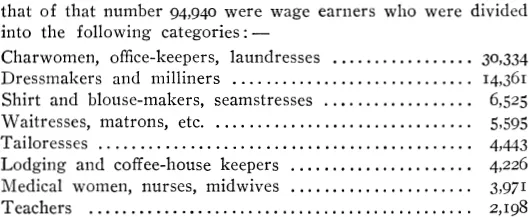

It was not unnatural, that the majority of the branches failed to comply with a request which obviously entailed a very extensive work. Nevertheless returns were sent in from between forty and fifty different towns and districts in various parts of the country and these showed the following results:2

On receiving these figures, the National Council of the Independent Labour Party decided to adopt the original Women’s Enfranchisement Bill, which passed its Second Reading in 1870. The text of the Bill was as follows:

In all Acts relating to the qualifications and registration of voters or persons entitled or claiming to be registered and to vote in the election of members of Parliament, wherever words occur which import the masculine gender the same shall be held to include women for all purposes connected with and having reference to the right to be registered as voters and to vote in such election, any law or usage to the contrary notwithstanding.

Meanwhile we of the Women’s Social and Political Union were eagerly looking forward to the new session of Parliament. It is indeed wonderful, in the midst of the great Women’s Movement that is present with us to-day, to look back upon its small beginnings in that dreary and dismal time not yet six years ago. It seemed then well-nigh impossible to rouse the London women from their apathy upon this question, for the old Suffrage workers had lost heart and energy in the long struggle and those who had joined them in recent days saw no prospect that votes for women would ever come to pass.

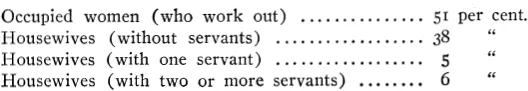

On the basis of Booth’s figures, Miss Clara Collett, the Government’s Senior Inspector for Women’s Industries, writing in the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society for September, 1908, estimated that the women occupiers of London might be divided as follows: —

I myself was then a student at the Royal College of Art, South Kensington, but I decided to absent myself in order to help my mother, who had come down from Manchester to “lobby,” as it is called, on those few important days. The House met on Tuesday, February 13, and during the eight days which intervened before the result of the Private Members’ ballot was made known we spent the whole of our time in the Strangers’ Lobby striving to induce every Member who had pledged himself to support Women’s Suffrage to agree that his chance in the ballot should be given to a Women’s Suffrage Bill. It was my first experience of Lobbying. I knew we had an uphill task before us, but I had no conception of how hard and discouraging it was to be. Members of Parliament all told us that they had pledged themselves to do “something for their constituents” or had some other measure in which they were interested, or had not been in Parliament long and preferred to wait until they had more experience before they would care to ballot for a Bill at all. Oh, yes, they were “in favour” of Women’s Suffrage; they believed that “the ladies ought to have votes,” but they really could not give their places in the ballot for the question; it was always “anything but that,” and during the whole of the week we spent in the Lobby we did not succeed in adding one single promise to that which we had originally received from Mr. Keir Hardie.

On the fateful Wednesday on which the result was declared, my mother and I were the only women in the Lobby. We sat there on the shiny black leather seats in the circular hall waiting for the result, and at last we saw with relief Mr. Keir Hardie’s picturesque figure coming hurrying towards us from the Inner Lobby. He was so kind and helpful, the only kind and helpful person in the whole of Parliament, it seemed. At once he told us that his name had not been drawn in the ballot and explained that only the first twelve, or, at most, fourteen, places that had been drawn could be of any use to the Members who had secured them, and that, owing to the limited number of days upon which private Members’ Bills could be discussed, only the first three or four had even a moderately good chance of becoming law.3 Our next move must therefore be to get in touch with the successful fourteen Members and to endeavour to persuade one of them to devote his place in the ballot to a Women’s Suffrage Bill. After considerable trouble we finally got into communication with all of them, and they all said “No,” with the exception of Mr. Bamford Slack, who held the fourteenth place, and who at last agreed to introduce our Bill, largely because his wife was a Suffragist and helped us to urge our cause. Of course the fourteenth place was not by any means a good one, and the Bill was set down as the Second Order of the Day for Friday, May 12.

In the meantime we drafted a petition in support of it and set ourselves to procure signatures. One Sunday evening I went with a bundle of petition forms to a meeting addressed by Mr. G. K. Chesterton at Morriss Hall, Clapham. The lecturer’s remarks were devoted to a eulogy of the French Revolution, from which he asserted all ideas of popular representation had sprung. An opening, which I seized, was given for a question on the subject of votes for women in relation to the Government of our Colonies. Whilst the audience were asking questions and offering criticisms, Mr. Chesterton was busily making sketches of us all, but, though I saw myself being added to the picture gallery, in replying to the questions raised in the debate afterwards, he did not answer my point. Afterwards, however, he came up and told me that he had forgotten to deal with it and then gave me an explanation. I had not asked, “Are you in favour of Votes for Women?” I had assumed that he was and he replied on the same assumption, and afterwards voluntarily signed his name to my petition. It was with surprise, not untempered with amusement, therefore, that I afterwards found Mr. Chesterton coming forward as an active anti-suffragist, but his attitude seemed to me to be an augury of our speedy success, for he delights to champion unpopular causes and to oppose himself to the overwhelming and inevitable march of coming events.

Many other women’s soci...