![]()

PART I

LIFE AND TIMES

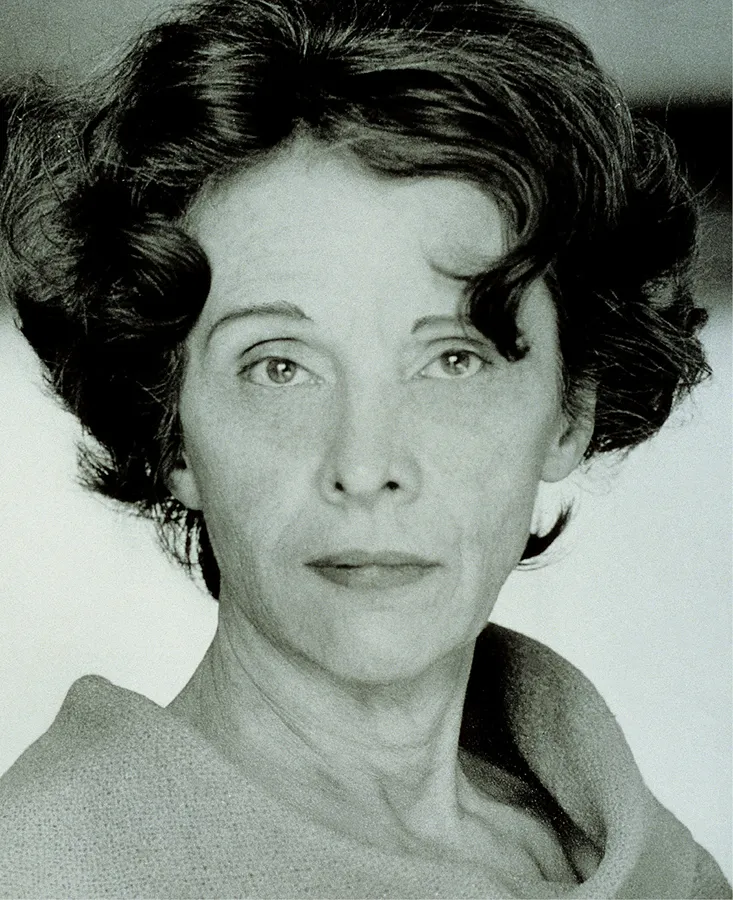

The story of Rowena Reed Kostellow’s life and work is inseparable from the story of American design education. She was present at the creation in 1934 of the country’s first industrial design department, at Carnegie Technical Institute. She came to Pratt two years later to help found the department in which she taught for fifty years, and she continued to teach private classes until just weeks before she died. Hers was a household name within the industrial design profession, but she left an equally important legacy in the students who established and taught in industrial design departments throughout the country and passed on her principles and methods in their own teaching.

Rowena taught two generations of teachers following her husband’s death, enlarging the circle of influence. Through her students-turned-educators, she made an enduring imprint on the teaching and practice of industrial design not only in the U.S. but beyond. Gerald Gulotta taught foundation principles in Guadalajara, Mexico; Craig Vogel applied them successfully in New Zealand; Cheryl Akner-Koler teaches them in the Department of Industrial Design at the University College of Art, Crafts and Design in Stockholm, Sweden.

Those who studied with Rowena didn’t easily forget her. Although she was a small-boned woman of medium height who rarely raised her voice, she was a person of commanding presence and demanded enormous effort from her students. Abstraction doesn’t come easily to most fledgling designers, but she insisted that an understanding of abstract visual order was at the heart of good design and that by perseverance and hard work, students could master that order. She refined a methodology for teaching that led students step by step to an understanding of and ability to use what she called the “structure of abstract visual relationships.”

The first generation of educators studied with both Rowena and her husband, Alexander Kostellow, considered by many to be the father of American industrial design education. That generation included Marc Harrison, at the Rhode Island School of Design; James Henkle, at the University of Oklahoma; Robert Redman, at the University of Bridgeport; Jay Doblin, at the Institute of Design in Chicago; James Pirkl and Lawrence Feer, at Syracuse University; Ronald Beckman, at Cornell; Nelson Van Judah, at San Jose State University; Read Viemiester and Budd Steinhilber, at the Dayton Institute of Art; Bernard Stockwell, at the Columbus College of Art and Design; Jayne Van Alstyne, at Montana State University; Robert W. Veryzer, at Purdue University; Charles W. Smith, at the University of Washington; Robert McKim, at Stanford University; Carl Olsen and Homer Legasy, at the School for Creative Studies in Detroit; and Joseph Parriott, Giles Aureli, Gerald Gulotta, and Lucia DeRespinis, at Pratt.

THE EARLY YEARS

Rowena Reed was born in Kansas City, Missouri, on July 6, 1900. One of three children of a doctor and his wife, she grew up in a prominent family, in a growing heartland city, in the optimistic early years of a new century. Her upbringing gave her an unshakable confidence and sense of entitlement that never left her. She entered the University of Missouri in 1918, intending to study art. “I didn’t know about three-dimensional design. I just took all the art courses I could take until there were no more,” she recalled in an interview in 1982. “But even then, in my untrained way, I knew I was wasting my time. They weren’t teaching me anything. There was no order, no organization, no continuity, nothing you could build on.” She majored in journalism, worked for a while as a fashion illustrator and, in 1922, enrolled in the Kansas City Art Institute.

There she met Alexander Kostellow, a Persian-born, European-educated artist who was beginning his teaching career as an instructor in painting. She was his student. He was, she said, “simply the most interesting man I’d ever met.”

Kostellow was a powerful personality. A graduate of the University of Berlin, with degrees in philosophy and psychology, he declined an invitation to join the German army during World War I and escaped the country through Holland, where he boarded a boat to the U.S. He jumped ship in Boston Harbor to avoid immigration officials, worked his way to New York, and studied for several years at the Art Students’ League, the New York School of Fine and Applied Arts, and the National Academy of Design.

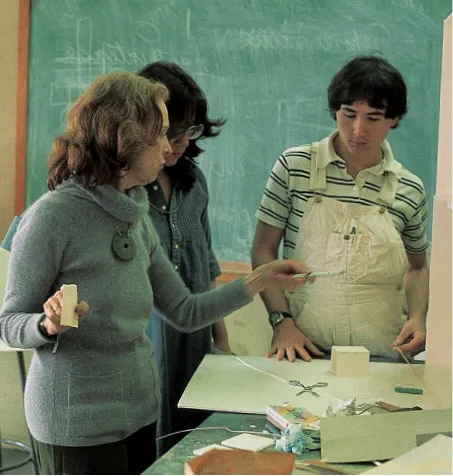

Rowena Reed’s 3-D design class

Kostellow felt the same way about his art education that Rowena Reed felt about her own. In 1947, he wrote: “My own experiences as an art student had not been too happy, because of the rather haphazard way one had to acquire the necessary knowledge and experience to become self-supporting in the field of art. Many of my fellow students were armed with plenty of patience and visions of ultimate glory, and spent years drawing casts in the national academies. Clearly it was a case of “life is short; art is long.” But to one who looked upon the graphic and plastic arts as a legitimate profession and part of our economic setup, and expected a definite type of fundamental training as a preparation for his career, the method was far from satisfactory.”*

Rowena Reed and Alexander Kostellow were married in Kansas City, and she returned with him to New York. There she studied sculpture with Alexander Archipenko. “I got a great deal from him,” she said. “His work is very profound and beautifully organized, but after I studied for a while, I came to feel that the one thing lacking in his work was an awareness of space.” That quest was to remain a driving force in her professional life.

In 1929, the couple moved to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where Kostellow had been hired to teach painting at the Carnegie Technical Institute. Rowena taught at a private school and worked as a sculptor. She and Alexander had a daughter, Adele, their only child, and together they pursued their interest in developing a structured language for understanding and teaching visual arts.

INVENTING INDUSTRIAL DESIGN EDUCATION

In 1933, Rowena went to Europe to study and spent a year on the continent immersing herself in painting and sculpture. She returned to a bustling, industrious city. Pittsburgh was the very heart of the steel industry, and despite the depression that ravaged much of the country, chimneys belched, machines bellowed, business hummed. And there were new currents in the air.

Chris Freas takes a close look during one of Rowena Reed’s Saturday class.

A decade earlier, American industry had begun to turn to specialists in the arts for help in designing and marketing products that would appeal to a growing audience of potential consumers. By the early 1930s, a small cadre of designers had emerged, Walter Dorwin Teague, Raymond Loewy, Henry Dreyfuss, Donald Deskey, Gilbert Rohde, Norman Bel Geddes, John Vassos, and Donald Dohner among them. These pioneers were staking out a new field, laying the groundwork for what would become the industrial design profession.

Dohner taught at Carnegie Tech. One day he was approached by an executive from Westinghouse, where he was a consultant, and, as Rowena Reed told the story, “The man said, ‘We have something out there in the plant that we don’t quite know what to do with. It’s a new material, and we want some ideas about how to use it.’ Well, Donald Dohner went out to look, and he saw big steel rollers with a rather innocuous material coming off them in sheets. First he said, ‘Let’s color it,’ so they created beautiful Mondrian-like reds, yellows, and blues, which made the material much more appealing. Then he said, ‘Let’s spin it,’ so they spun some trays—beautiful contemporary trays that people would be delighted to buy. After a while, they made them deeper and added a few bowls and other simple shapes. The material was the melamine plastic stuff that now covers all of our homes and all of our lives. They called it ‘Micarta.’”

Dohner’s experience convinced Kostellow that the opportunities in American industry were there for the taking. The time had come to formalize design training for a new design discipline. He had already spent years experimenting with ways to bring focus and order to art education and gaining direct experience as a design consultant to several firms in the area. So he and Dohner went to the Carnegie Tech administration and proposed the establishment of a degree-granting program in industrial design. They successfully argued their case, and in 1936, the Department of Industrial Design, the first of its kind in the United States, graduated its first students.

The industrial design experiment opened a new world for Rowena Reed. It fired her imagination and focused her interest on three-dimensional design. In 1938, she became formally involved in the design venture. Donald Dohner had been invited to Pratt Institute in 1934 by Dean James Boudreau to establish an industrial design department there. Dohner persuaded Kostellow to follow him to Brooklyn to develop the curriculum and teach courses in color and design. He asked Rowena to teach abstraction. Of their early work at Pratt, Arthur Pulos writes: “With Alexander Kostellow representing the philosophical, Rowena Reed the aesthetic, and Dohner the practical, they laid the triangular foundation for Pratt’s program in industrial design.”*

They were joined by Frederick Whiteman, Robert Kolli, Ivan Rigby, and Rolph Fjelde, and soon after by Eva Zeisel and Victor Canzani.

“In the beginning it was so great because we all spoke the same language,” Rowena recalled. “It was awfully exciting. We were young and inconsiderate—the only way to get things done.”

Their first big accomplishment was the development of a curriculum of study for all first year students in the art school. It was called, appropriately, “foundation” and was the first course of its kind specifically designed to address the requirements of the American art student and American society. It grew out of Kostellow’s own experiences with pictorial structure and organizing the axes on the canvas, and out of Reed’s experiments with visual organization in three dimensions. It became the prototype for foundation programs in many other schools across the country.

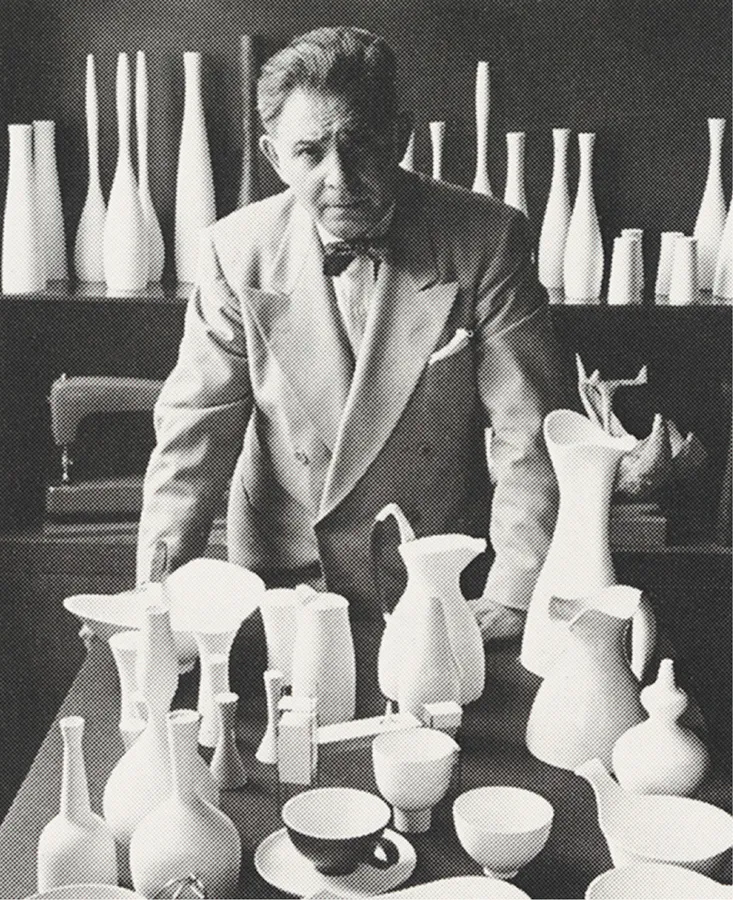

Alexander Kostellow in Interiors magazine

Alexander Kostellow described the intention of the program: “The goal was to supply students not with disjointed bits of information but rather with an organized approach to the mechanics of design and the necessary inner discipline to carry out assigned problems…to develop an understanding of the elements of design, of structure, of the organizational forces which control them, and an ability to apply this knowledge to a variety of situations in designing for self-expression or for industry.”

The program was general in its approach to the visual disciplines because, Kostellow wrote, “experience proves that specialized courses in design, like other programs devoted to the development of technical skills, restrict the esthetic potential of the student. Practical approaches rarely bring forth creative designers of importance. At best they produce skilled technicians.”

Frederick Whiteman, who taught 2-D courses in the foundation year, saw foundation studies filling a vacuum that the academy itself had created. “Under the old apprentice system students could work on parts of a work, but only the master could put it together,” he declared. “The commercial art schools took away the master. Now all students were drawing fragments, but they never learned to put it together. That is, they never learned to design. Foundation taught how it all went together.”

Three years after Kostellow and Dohner established the industrial design department at Carnegie Tech, the New Bauhaus opened in Chicago. Mies van der Rohe moved it to IIT in 1938, where it later became the Institute of Design within the Illinois Institute of Technology. Directed by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, the New Bauhaus promoted the course of study established by Walter Gropius at the original Bauhaus.*...