CHAPTER 1

“Digging for Deferments”

World War II, 1940–1945

Just weeks before the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor, Gen. J. O. Donovan, the state director of Selective Service for California, wrote the agency’s central headquarters in Washington, D.C., asking for advice. It seemed that a particular registrant had requested a deferment from induction because, he stated, his wife was pregnant. The man’s local board, however, had reason to question the legitimacy of the registrant’s claim and wished to submit the man’s wife to a pregnancy test at the state’s expense. Donovan wanted to know if the national office would reimburse the California office for the cost of the test. Col. Carlton S. Dargusch, the deputy director of Selective Service, responded promptly. Yes, he replied, Donovan could authorize the test at government expense after “due examination” had established its necessity.1 This case was not unique. The Selective Service tried to make clear to the states and to local boards that it was the responsibility of individual men to pay any costs associated with proving dependency claims, but there are other examples of the agency reimbursing states for pregnancy tests.2

Asking women, who were theoretically outside of the purview of the Selective Service, to submit to medical exams was perhaps the most invasive example of the Selective Service digging into the private lives of registrants and their families during what became the World War II draft, but it was not the only one. Many local boards spent considerable time and resources investigating individual families to determine whether and to what extent the men materially contributed to family resources and when children had been conceived before granting draft classifications.3 By 1943, the Selective Service had a detailed policy on determining the date of a baby’s conception that included discussion of a woman’s menstrual cycle and methods of counting forward from the first day of her last period or the baby’s quickening and backward from its delivery date.4

As this example illustrates, the issue of deferments bedeviled the Selective Service throughout the war. It was an agency that justified its mission based on the idea that all able-bodied men within a given age range had an equal obligation to serve in the military but that not all of these men could be spared equally from the civilian economy. America’s “arsenal of democracy” had to be supplied and fed, and many men otherwise qualified for military service could not be replaced easily if conscripted because they possessed skills needed in the civilian world. The key was developing the criteria on which decisions could be made about which men should remain civilians and which could be spared for military service.

By 1945, the Selective Service had classified most men between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five as eligible for military service. The diversity of men classified as available undeniably made the American military of World War II a citizen army. Just under 16 million men served in the armed forces between 1940 and 1945 out of a total population of 130 million, including women, children, and the aged. In other words, approximately 12 percent of the entire American population performed some type of military service during the war years, and scholars have estimated that a full 80 percent of the men born in the 1920s served in uniform.5 These men came from all walks of life, all races, all socioeconomic levels, and all levels of educational attainment. They were from all regions of the country and had ancestry from all over the globe. The vast majority never considered military service until the war began and did not envision staying in the military afterward. The military was racially segregated, but, taken as a whole institution, it was diverse and filled with men oriented more toward the civilian world than toward professional soldiering.

But what is frequently lost in this statistical picture is that many, many individual men were more than happy to take advantage of the legal deferments offered them by the Selective Service during the early years of the war, and they resisted the loss of those deferments as the war progressed. Military service was not a given for a large proportion of the American male population. Although they tended not to call attention to their actions, many men sought any legal avenue they could find to avoid military service. In so doing, they took advantage of the mechanisms for deferment created by the Selective Service, much to the chagrin of Selective Service officials.

Determining the dividing line between draftable and nondraftable men provides the central tension of any system of selective military service. What is striking, however, is that through at least 1943, the calculus over which men should serve and which men should remain civilians was not solely related to how a man’s job supported the war effort. Instead, laws passed by Congress, Selective Service regulations, and the on-the-ground practice of individual local draft boards reflected a national belief in the importance of men as the financial and moral center of the household. Cultural values about the domestic responsibilities of husbands and fathers suffused the entire system, and whether it wanted to or not, during World War II—as during previous American wars—the Selective Service had to grapple with these cultural values. Dependency deferments, which were created to support alternate visions of male responsibility, including breadwinner and father, created loopholes in the draft, which is precisely why the Selective Service found itself ordering pregnancy tests.

As the war deepened and manpower needs increased, procuring enough men to expand the armed services became more important. After significant political and public debate, Congress and the Selective Service rescinded deferments that protected husbands and fathers. Occupational deferments, the major remaining category of deferments, continued to shelter men who held jobs in essential industries and in agriculture, but this classification was defined specifically as supporting the military effort in Europe and Asia rather than protecting domestic morality. It was based purely on national defense considerations, as the needs of a total war effort ultimately trumped the needs of individual families. The resultant wide net that put so many men into uniform made it appear in retrospect that men’s patriotism and deeply felt responsibility to defeat the Axis powers had driven America’s victory against fascism. Certainly that is the narrative created by the myth of the “greatest generation,” but such widespread participation in the armed forces was far from automatic. Uniformed service was contested during World War II—not to the scale it would be in later years— but in a more significant way than is generally acknowledged. Even during the so-called “Good War,” the links between masculine forms of citizenship and military service were not as strong as many Americans believe.

When Americans of the early twenty-first century reflect back on World War II, the image that most conjure is some version of the myth of the “Good War.” They envision the era as one of unity and consensus, when their forebears came together to beat truly evil enemies. The cause was just, the people patriotic, and the soldiers brave. There was no moral ambiguity. The sacrifices war required were difficult, but they were shared and bore dividends in the form of good jobs during the war and prosperity afterward that few could have dreamt of during the prior decade of depression.6

Special attention is lavished on the men who served in the military. According to the common narrative, men, regardless of how they ended up in the armed forces, fulfilled their responsibilities as citizens through military service, and—through their manly sacrifice and the GI Bill—earned the educational and economic opportunities that allowed them to become successful masculine breadwinners after the war. Military service more than any other factor defined the so-called greatest generation. Male veterans of this generation have been described as daring, brave, uncomplaining, innovative, persistent, and humble.7 They “spread the lesson of tolerance throughout the country.”8 In American cultural memory, widespread military service during World War II turned hyphenated Americans into full Americans, boys into men, and the United States into a world power.9

Scholars have debunked most of these myths, describing them as incomplete at best. While Americans did come together in ways they rarely had before or since, they did so kicking and screaming. Political parties squabbled over the best way to finance and run the war, military officials disagreed with civilian ones, government agencies jockeyed for power, labor clashed with management, race riots erupted in cities like Detroit and Los Angeles, Japanese Americans were incarcerated in camps without the right of due process, lynchings and more subtle forms of racism continued unabated, women struggled to gain respect in the workforce, children faced upheaval as parents left home for work and the front.10 Even in 1944, three years after the start of the war, polls indicated that up to 40 percent of the population did not know why the United States was fighting.11 For families who lost loved ones, the notion of a “good war” would have seemed strange indeed.

In fact, the popular linking of the World War II generation with these characteristics—fearlessness, strength, selflessness, manliness—was the result of careful and conscious image production both during and after the war. This was particularly true with regard to military service. Prior to World War II, military service was a profession viewed with suspicion.12 In the colorful words of one observer, the popular perception of the American soldier in 1942 was “still a national guard jag staggering drunkenly down the street at two a.m.”13 During the war, however, government and civilian sources alike used images of soldiers to embody a renewed American muscularity after the impotent years of the Great Depression. They were used as a symbol of masculine patriotism through which all Americans could confirm their citizenship.14 They became “the personification of the cause” that gave “America a beautiful personal stake—emotional stake—in [the war’s] success.”15 Such imagery became necessary because neither the federal government nor private interests were able to persuade Americans that they should fight out of political obligation.

Instead, media—from both public and private sources—purposely connected the ideas of manhood and moral responsibility. Organizations, groups, and companies from the War Department to the American Red Cross, from Coca-Cola to Community Silverplate, which manufactured silverware, encouraged men to join the military and risk their lives because it was their manly responsibility to protect their loved ones.16

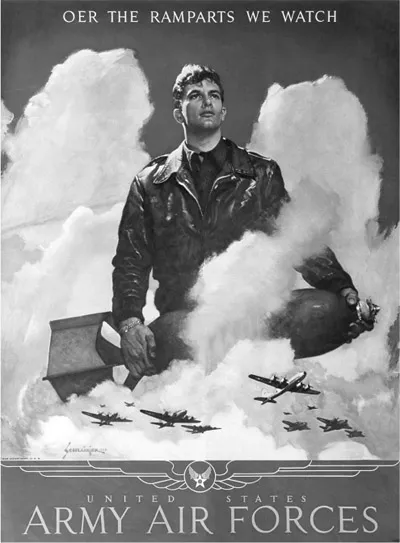

FIGURE 1.1. “O’er the Ramparts.” This poster, created by Jes Wilhelm Schlaikjer in 1945, advertised the valor of American soldiers serving in the Army Air Forces. It used a number of masculine tropes common to American patriotic imagery during World War II. Note the figure’s strong hands, broad shoulders, chiseled jaw, and determined yet wistful expression. Photo courtesy of Northwestern University Library, https://images.northwestern.edu/multiresimages/inu:dil-4d5f2160-973b-46f3-938c-3310031e8816.

Historian Christian Appy has termed this type of imagery “sentimental militarism,” a media trope that constructed the GI as a peace-loving American reluctantly fulfilling his citizenship obligations in order to protect his loved ones, proving his patriotism and manhood in the process.17

Informational campaigns reminded the public that men in essential war industries “fought” the enemy and were therefore necessary to the war effort. They, too, could be protectors.

Yet the dominant cultural message of the war years clearly elevated those who served in the mili...