eBook - ePub

Yoga

Its Scientific Basis

Kovoor T. Behanan

This is a test

Share book

- 294 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Yoga

Its Scientific Basis

Kovoor T. Behanan

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Clear explanation and evaluation of fundamental concepts of Hindu thought; historical synopsis of the development of Hindu religious philosophy; detailed descriptions of the psychology and psychoanalysis of yoga, its postures and varieties of breathing; exercises in concentration — even methods by which yogis achieve muscular control over bodily functions.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Yoga an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Yoga by Kovoor T. Behanan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophie & Philosophies orientales. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

PhilosophieSubtopic

Philosophies orientalesCHAPTER I

THE APPARENT COMPLEXITY OF INDIAN CULTURE

No WORD can bring to Western minds a greater number of esoteric associations than the name India. The enticement of romance, the lure of gold and diamonds, wanderlust, a desire to face the tiger in the jungles of Bengal, the reputed unerring precision of the mongoose in subduing the cobra, or even a sneaking suspicion that there is a catch somewhere in that tall “rope-trick story”; these and many others are mingled together as elements in a hazy picture of India. While there is a basic residuum of truth in such a conception, a correct understanding of the complexity of modern India is impossible without some historical knowledge of the cultural evolution of the country.

The cultural history of India begins with the Aryan invasion. Leaving aside for the moment the vague origins of what is now one of the oldest cultures of the world, we may profitably summarize the high points of India’s later history. Although thousands of miles away from Europe, India has figured recurrently in historic times as the goal of a succession of military conquests from the Western world. Blazing new trails and overcoming great obstacles, Alexander the Great of Macedon subjugated the northwestern regions of India in 326 B.C. He came not to establish a kingdom, but merely to conquer. Like a bird of passage he disappeared soon after his arrival. The cultural influence of this invasion survives today in some of the architectural monuments of North India.

During the next great wave of conquest, which began in the eleventh century and finally culminated in the establishment of the Mohammedan Empire, Europe lost contact with India. But with the breakup of feudal Europe and the beginning of the modern era of Western expansion, a sea route to India was discovered by the Portuguese. After a period of struggle for power between the various nations of Europe, the English established their rule and built an Indian Empire on the ruins of that of the Mohammedans, which had been slowly disintegrating since the beginning of the eighteenth century. The coming of the English to India was in many respects different from the previous conquests, in that two distinct cultures came into intimate contact with one another. After the consolidation of their political power, English scholars were not slow in initiating research in various directions to reconstruct India’s past.

What strikes any keen student of present-day India is its incomprehensible diversity. It is a veritable museum of beliefs, a finely interwoven tapestry of multifarious sects and secret rites. Side by side with the most abstruse and sublime metaphysical speculations about the nature of reality, one may see primitive animistic beliefs and worship of natural forces. The introduction of Western education has made these anachronisms all the more incongruous. Until recently, for example, there existed in a section of the country a hospital for rats endowed by public subscription! What can be more paradoxical to the Westerner than the sight of painted, sacred bulls mingling nonchalantly with the pedestrians on the streets of Calcutta, the second largest city in the British Empire?

Social life is even more incomprehensible–a rigid caste system, with the Untouchables at the bottom and the Brahmins at the top, is the very bedrock of Indian civilization. The rigidity of such social stratification is to be seen in two communities of fishermen in a certain section where the members of one weave their nets from right to left and the other from left to right; there is no intermarriage between the two groups.

Religion, like salt in the ocean, pervades all aspects of life. Because of the religious sanction which underlies all social institutions, caste has continued to flourish for centuries in spite of the moral and material degradation to which a vast number of India’s population has been consigned. Even highway robbery was once considered as having religious sanction. A “thug” in American newspapers is an armed robber. But the name is derived from a North Indian community of the last century, whose members not only gained a livelihood through armed robbery but considered it a religious duty.

The contradiction between theory and practice and the wide prevalence of the most barbaric social customs and religious practices alongside sublime philosophic thought and ideals of self-abnegation have led many modern observers to contradictory evaluations of India’s culture. But this contradiction would fade away on deeper analysis. The sociologist and the social psychologist aim to understand culture. They are not averse to introducing changes in society, though they do not consider it their province. On the other hand, reformers all over the world have one thing in common, namely a desire to change existing institutions when they have outlived their usefulness. Their praise and blame are influenced by relative standards of what is, or what is not, desirable. A modern example may help us here. The reformers of the extreme left today attribute all the ills of society to the private ownership of the means of production, hence, they clamor for a collectivist society. But such an attitude does not help us to understand how and why private ownership became an economic institution all over the world. To comprehend this, it is necessary to study the various factors which influence the evolution of changing relationships in the means of production. Without an understanding of the past the present becomes inexplicable.

Gradual evolution from lower to higher forms is the pivotal truth of biology; forms of thought and attitudes toward life, religion, and philosophy are also better understood in terms of evolution. Ancient Greece and Rome are dead, but who would deny that the legacy of these two civilizations may be traced in modern Europe and America? The exaggerated dictum that nothing moves in the world that is not Greek in origin may be true of the West, but it is equally true that India moves on foundations that are thoroughly Hindu in origin.

With the exception of the Chinese, Indian civilization is the only one that has come down to us from antiquity with an unbroken tradition. Conquerors may have come and gone and at Delhi may be seen the ruins of half a dozen empires, but the culture of India has remained untouched through the ages. In spite of repeated political convulsions, religious reforms, and foreign invasions, the spirit of Hindu culture today is not very different from what it was centuries ago. Today, after nearly two centuries of British rule, the ways of the man in the street remain unchanged. Politically and economically, in India, as everywhere else, threatening clouds are gathering on the horizon. Whether this will lead to a disintegration of the age-old Hindu culture remains to be seen. The words of the English historian, V. A. Smith, are very significant in this connection:

European writers, as a rule, have been more conscious of the diversity than of the unity of India. . . . India beyond all doubt possesses a deep underlying fundamental unity, far more profound than that produced either by geographical isolation or by political suzerainty. That unity transcends the innumerable diversities of blood, colour, language, dress, manners, and sect.1

It is generally believed that the important factor which makes for this unity has been the Hindu religion and its philosophical tenets. And so, if we are to understand yoga, which is an important part of the philosophical tradition, in its natural setting in Hindu thought and with a correct perspective, it is necessary to trace briefly the history of this culture with reference to religion and philosophy.

Evidence gathered from the earliest Indian literature leads us to believe that a group of warlike tribes invaded India from the northwest and spread to the east and to the south, subjugating the natives and imposing their speech and civilization upon them. The exact date of this invasion remains conjectural, but was probably the first half of the second millennium B.C.

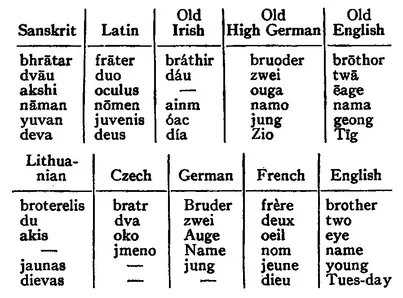

The language spoken by these tribes was the earliest form of Sanskrit, the classical language of India. In the beginning of the last century, the first generation of scholars that studied India’s past discovered that Sanskrit was closely related to several European languages. This group of languages, known as Indo-European, may be traced all the way from Western Europe to the banks of the Ganges. The following list of words gives an indication of this interrelationship: 2

The philologists soon concluded that a race of people known as Aryans must have lived, in pre-historic times, in their original home somewhere in Central Asia or Eastern Europe. In the third or second millennium B.C. they migrated in various directions, the tribes that spoke Sanskrit and that invaded India being the most easterly branch of this race. For a long time it was the pastime of the philologists to attribute superiority of mental development and the great achievements of the ancient world to the Aryans who were regarded as a distinct race. The latest excavations in Mesopotamia and Egypt have taught us to think differently. The concept race in its original sense has no meaning, and the present tendency is to discard the word and substitute “ethnic group” (a group sharing the same culture, irrespective of the ancestry of its members) in its place. But the human mind is so prone to accept what is pleasing that the word “Aryan” has been resurrected for political purposes in Germany.

When the invaders poured into India from the northwest they were confronted with dark-skinned, long-nosed aborigines. What little culture these indigenous peoples possessed was either destroyed or absorbed by the conquerors. Since we have had only glimmerings of the period preceding the Aryan conquest, it has been taken for granted that the second millennium was the dawn of civilization in India. But a new chapter of India’s pre-historic past has been suddenly opened by the accidental discovery, about a decade ago, of the site of Mohenjo Daro in the Indus valley. No less than ten superimposed pre-historic cities have been identified, although only the latest three have been explored. According to Sir John Marshall, the leader of the excavations, “. . . the civilization of which we have now obtained this first glimpse was developed in the Indus valley and was probably as distinctive of that region, as the civilization of the pharaohs was distinctive of the Nile.”3

It is too early to decide the racial origin of the people who evolved this civilization, since it came to an end about 3000 B.C., but it has been suggested that it was probably destroyed by the conquering Aryans. Or, on the contrary, it may have died out leaving no observable influence on the later development of civilization in India.

After this brief historical digression we may now come back to the culture as revealed in the earliest literature which originated with the Aryans. The word “Veda” (from vid, “to know”) means “sacred knowledge or Scripture” and the first compositions, four in number, are known as the Vedas. For the most part these books contain collections of sacrificial hymns sung on religious occasions. The recovery of the Vedas and the extensive work of scholars like Max Müller in interpreting this literature have revealed a fascinating side of Indian history. It has been clearly established that writing was unknown in India before the fourth century and the oldest known inscriptions do not go back further than the third century B.C., whereas the oldest extant manuscripts of the Vedas belong to the sixteenth century A.D. Yet it has been established beyond doubt that the major part of the Vedas was composed before 1000 B.C. Evidently these hymns were handed down from generation to generation by a select group of people who learned the passages by heart. Take, for example, the Rig-Veda. It is the oldest product not only of the Indian, but of the Indo-European literature, consisting of 1017 poems, 10,550 verses, and about 153,826 words. When Max Müller, toward the end of the last century, decided to translate and publish the Rig-Veda, instead of collecting manuscripts, as scholars do in Greek and Latin, various Vedic students were asked to recite the whole book from memory. Strikingly enough, if every manuscript of the Rig-Veda were lost today, we should be able to recover the whole of it from the memory of professional Vedic students known as Srotrayas. Inasmuch as oral transmission is a religious function, the candidates are selected at a very early age and made to undergo vigorous physical and spiritual discipline in preparation for their task. Eight years spent with a teacher (guru) is the minimum.

The Rig-Veda and the culture it reveals remind one of the Iliad of the Greeks. In both literatures we have a picture of a society molded by invasions, showing the full vitality of the conquerors. Nobles and kings ruled the various tribes. The indigenous peoples were enslaved. The unit of society was the patriarchal household of freemen; farming and sheep-grazing the means of livelihood.

To the student of the evolution of thought, the religious ideas embodied in the Vedas are of paramount importance, for here we see the development of mythology, magic, and religion from a very primitive to an advanced form. Every phenomenon of nature which showed power and beauty was personified. The Sun, Dawn, Rain, Thunder, Rivers and Mountains, all became gods and rulers of the world. Their food is the same as that of men. They could be placated by sacrifices and made to bestow gifts on men. The world was pictured as a cosmic Punch and Judy show, controlled and administered by the will of the divine officers.

One stage of great importance in the evolution of religion, in general, is the attribution of moral majesty or goodness to the deities. This is nowhere to be found in Vedic religion. Shepherd tribes migrating constantly could not be expected to devote any serious and consistent thought to ethical problems. Material comfort, not soul-searching philosophy, dominated the minds of the Vedic people.

The Vedas were followed by a group of theological treatises. (Brahmanas), written in prose, detailing minutely the various steps in sacrificial ceremonials. The priest became the guardian of the secrets of sacrifice and thus gained a dominant position in social life. The theological intricacies and hair-splitting arguments of this literature present a close parallel to the Hebrew Talmud. The four castes and their duties are mentioned for the first time in these books, which consequently shed considerable light on the social origins of caste and the vulgarized nature of the organized religious forms of a later period.

The whole of India was not caught in the meshes of this popular theological religion and ritualism. We find the emergence of a number of treatises known as Upanishads containing a highly idealistic exposition of the problems of philosophy and metaphysics. These became the basis of all the subsequent schools of philosophy in India. The subject matter of all these volumes is essentially the same: i.e., speculations on the nature of the supreme soul. They constitute the latest phase of the Vedic literature. Before proceeding any further we would do well to recapitulate the main trends of our discourse thus far.

We have said that the Vedic period began with the conquest of the Aryan tribes sometime in the early part of the second millennium. The simple civilization of the pastoral people embodied in the Vedas was followed by one in which the priests, by becoming the custodians of sacrifice, began to exercise economic and social power and influence. It was primarily against the moneymaking priests that Buddha directed his reform movement in the sixth century B.C. But the hold that the sacrificial mysteries had gained over the masses was a strong one, and with characteristic human intolerance the priesthood spared no pains in rooting out of India the teachings of Buddha.

The precepts of the Upanishads (c. 1000-sixth century B.C.) constitute a new turn in the development of Indian thought, having nothing to do with the old theological magic of the priests. Inasmuch as the teachings contained in the Upanishads were aimed at the salvation of the soul, and not concerned with the reformation of society, like those of Buddha, they did not fall under the ban of the official priesthood. This period of daring speculative philosophy came to a close around 300 B.C. Modern India becomes less of a paradox when we realize that these two traditions, the sacrificial religion of the masses which is dominated and controlled by the priests and the philosophic idealism of the Upanishads (which is free from the shackles of caste and creed), have continued to flow along side by side ever since they came into existence in the later Vedic period.

We turn now to the Upanishads. The word literally means “secret teachings”. Since the distinctive character of the Upanishadic doctrines constituted an uncompromising departure from the prevailing sacrificial religions, it is very probable that certain formulae embodying philosophical principles–as for example, tat tvam asi, meaning the identity of the cosmic (Brahman) and individual souls (Atman)—were communicated by the teacher to the disciple as hidden truths to be guarded as priceless treasure. In the course of time, when the various literatures were brought together, the Upanishads were appended to the end of the Vedas; hence the name Vedanta, 4 which literally means “end of the Vedas”. It was in the same way that Aristotle’s Metaphysics received its designation; because it was placed after his writings on Physics.

More than two hundred Upanishads are known to be in existence, some of them having been composed as late as the eighteenth century A.D. It has been established, however, that the most important of them, about twelve in number, were actually composed after the completion of the Vedic hymns and before the Buddhist period (c. 1000-sixth century B.C.). The style of presentation is mostly in ...