The simplest way in which a scientist can actively seek knowledge is deliberately to exploit a natural process, but a process which he cannot control. In this section I describe two investigations, the one by Aristotle on the embryology of the chick, and the other by William Beaumont on the process of digestion. In both cases a natural process was isolated and systematically observed; but its unfolding was not able to be controlled.

1. Aristotle

The Embryology of the Chick

Aristotle was born in Stagira, a Greek colony in Asia minor, in 384 BC. His father was a doctor, a member of the guild of the Asclepiadae. Aristotle was orphaned while still a child, and brought up by a relative. It does seem likely that even while very young he had some training in medical and biological matters from his father.

At the age of eighteen he entered Plato’s Academy at Athens, and remained there until Plato’s death in 347 BC. As a young man he seems to have cut something of a figure. Anecdotes about this period in his life suggest that he attracted a certain amount of envy for his stylish manners and intellectual advantages, a combination of qualities hard to forgive in any age. After Plato’s death he left Athens for Atarneus. This was a small state whose ruler, Hermias, had collected a circle of scholars influenced by Plato’s teachings. Shortly after his arrival Aristotle married Hermias’s adopted daughter, Pythias. They had only one child, a daughter called after her mother. After his wife’s death Aristotle set up house with a woman called Herpyllis, though it seems he never married her. Nicomachus, their son, was the recipient of the moral treatise from his father that has come down to us as the Nicomachean Ethics.

Aristotle stayed at Atarneus for three years, and then moved to Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. It seems likely that he made most of his biological investigations while living there. Sometime in 343–342 he was invited to tutor Alexander, the son of Philip of Macedon. Eight years later he returned to Athens and founded his own school and library, the Lyceum. Schools like the Academy and the Lyceum served some of the functions of modern universities, though they were not so formally organized.

By 322 feeling had turned against the Macedonians and Aristotle retired to Chalcis. He remarked that he did not want to give the Athenians a chance to destroy another philosopher, as they had Socrates. He died in Chalcis shortly afterwards.

Fig. 8: Portrait bust of Aristotle. Rome, Terme Museum.

Theories of organic generation before Aristotle

With Darwin, Aristotle must surely be ranked as among the greatest biologists. He was one of the very first to carry out systematic observations and to write a detailed work on organic forms, known to us as the Historia Animalium. The experiment I shall be describing laid the foundations for all subsequent embryological work. It is remarkable both for its systematic character, and for the shrewdness of the questions Aristotle was prompted to ask by the results of his investigations.

The problem of the nature of ‘generation’, the way animals and plants came into existence, had been quite deeply considered by Greek thinkers before Aristotle. How does a new plant or animal come into being? It seems to be formed out of some basic undifferentiated stuff, and yet it quickly takes on a most refined and articulated structure. Is that structure just a filling out of a pre-existing plan (the theory of pre-formation), or does it come into being stage by stage, as the various phases of the growth process unfold (the theory of epigenesis)? The problem is not wholly solved even today. Attempts to understand the process of generation are very ancient, and already in 345 BC Aristotle was the inheritor of a body of doctrine from a long line of predecessors interested in the problem.

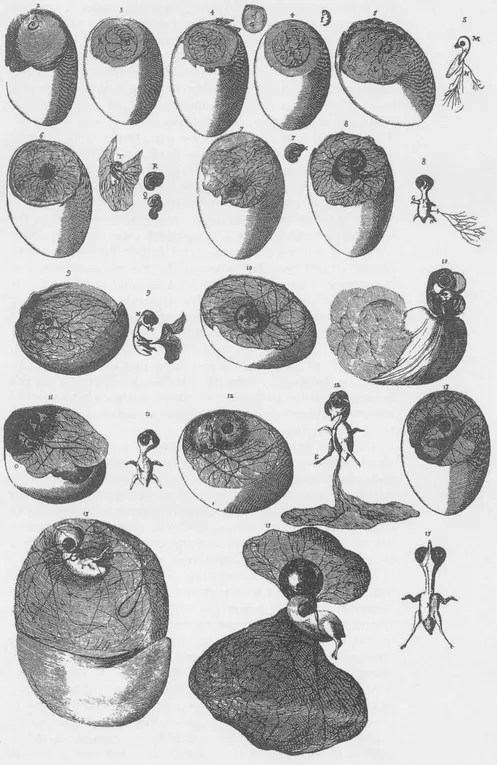

The only medical treatises of worth to come down to us from the times before Aristotle are the Hippocratic writings. Whoever wrote these works had a very clear idea of the possibilities of comparative embryology of non-human species as an approach to the problem of how new human beings are created. In the work On the Nature of the Infant an exploratory study is suggested in the clearest terms. ‘Take twenty eggs or more, and set them for brooding under two or more hens. Then on each day of incubation from the second to the last, that of hatching, remove one egg and open it for examination. You will find that everything agrees with what I have said, to the extent that the nature of a bird ought to be compared with that of a man.’ Commentators on these writings seem to be agreed that the text does not suggest that the author actually followed his own prescription. That was left to Aristotle. Here is his description of the embryonic stages in the development of the chick.

The opening of the eggs

‘Generation from the egg proceeds in an identical manner with all birds, but the full periods from conception to birth differ, as has been said. With the common hen after three days and three nights there is the first indication of the embryo; with larger birds the interval being longer, with smaller birds shorter. Meanwhile the yolk comes into being, rising towards the sharp end, where the primal element of the egg is situated, and where the egg gets hatched; and the heart appears, like a speck of blood, in the white of the egg. This point beats and moves as though endowed with life, and from it two vein-ducts with blood in them trend in a convoluted course [as the egg-substance goes on growing, towards each of the two circumjacent integuments]; and a membrane carrying bloody fibres now envelops the yolk, leading off from the vein-ducts. A little afterwards the body is differentiated, at first very small and white. The head is clearly distinguished, and in it the eyes, swollen out to a great extent. This condition of the eyes lasts on for a good while, as it is only by degrees that they diminish in size and collapse. At the outset the under portion of the body appears insignificant in comparison with the upper portion. Of the two ducts that lead from the heart, the one proceeds towards the circumjacent integument, and the other, like a navel-string, towards the yolk. The life-element of the chick is in the white of the egg, and the nutriment comes through the navel-string out of the yolk.

When the egg is now ten days old the chick and all its parts are distinctly visible. The head is still larger than the rest of its body, and the eyes larger than the head, but still devoid of vision. The eyes, if removed about this time, are found to be larger than beans, and black; if the cuticle be peeled off them there is a white and cold liquid inside, quite glittering in the sunlight, but there is no hard substance whatsoever. Such is the condition of the head and eyes. At this time also the larger internal organs are visible, as also the stomach and the arrangement of the viscera; and the veins that seem to proceed from the heart are now close to the navel. From the navel there stretch a pair of veins; one towards the membrane that envelops the yoke (and, by the way, the yolk is now liquid, or more so than is normal), and the other towards that membrane which envelops collectively the membrane wherein the chick lies, the membrane of the yolk, and the intervening liquid. [For, as the chick grows, little by little one part of the yolk goes upward, and another part downward, and the white liquid is between them; and the white of the egg is underneath the lower part of the yolk, as it was at the outset.] On the tenth day the white is at the extreme outer surface, reduced in amount, glutinous, firm in substance, and sallow in colour.

The disposition of the several constituent parts is as follows. First and outermost comes the membrane of the egg, not that of the shell, but underneath it. Inside this membrane is a white liquid; then comes the chick, and a membrane round about it, separating it off so as to keep the chick free from the liquid; next after the chick comes the yolk, into which one of the two veins was described as leading, the other one leading into the enveloping white substance. [A membrane with a liquid resembling serum envelops the entire structure. Then comes another membrane right round the embryo, as has been described, separating it off against the liquid. Underneath this comes the yolk, enveloped in another membrane (into which yolk proceeds the navel-string that leads from the heart and the big vein), so as to keep the embryo free of both liquids.]

About the twentieth day, if you open the egg and touch the chick, it moves inside and chirps; and it is already coming to be covered with down, when, after the twentieth day is past, the chick begins to break the shell. The head is situated over the right leg close to the flank, and the wing is placed over the head; and about this time is plain to be seen the membrane resembling an after-birth that comes next after the outermost membrane of the shell, into which membrane the one of the navel-strings was described as leading (and, by the way, the chick in its entirety is now within it), and so also is the other membrane resembling an after-birth, namely that surrounding the yolk, into which the second navel-string was described as leading; and both of them were described as being connected with the heart and the big vein. At this conjuncture the navel-string that leads to the outer after-birth collapses and becomes detached from the chick, and the membrane that leads into the yolk is fastened on to the thin gut of the creature, and by this time a considerable amount of the yolk is inside the chick and a yellow sediment is in its stomach. About this time it discharges residuum in the direction of the outer after-birth, and has residuum inside its stomach; and the outer residuum is white [and there comes a white substance inside]. By and by the yolk, diminishing gradually in size, at length becomes entirely used up and comprehended within the chick (so that, ten days after hatching, if you cut open the chick, a small remnant of the yolk is still left in connexion with the gut), but it is detached from the navel, and there is nothing in the interval between, but it has been used up entirely. During the period above referred to the chick sleeps, wakes up, makes a move and looks up and chirps; and the heart and the navel together palpitate as though the creature were respiring. So much as to generation from the egg in the case of birds.’

(Historia Animalium, book 6, 561a3-562a20)

Fig. 9: Embryo chicks at different stages of development. Engraving from H. Fabricius, De Formatione Ovi et Pulli, Padua (1621).

Embryology after Aristotle

No doubt interest in embryology continued after Aristotle’s time, particularly in widening the scope of observational and experimental studies. But very little of the work of Hellenistic science, from the great schools of Alexandria, has come down to us. Medieval Europe learned most of its Greek science from Arabic authors, who had transmitted and enlarged the ancient learning. Amongst the most important sources of medical and biological knowledge were the works of Galen and Avicenna. But medieval science, for the most part, returned to Aristotle as an ultimate source, so that new work was usually the result of critical commentaries on surviving Aristotelian treatises. In particular medieval embryology was closely modelled on the section I have quoted from Aristotle’s Historia Animalium.

One of the most sophisticated treatises on generation, in the Aristotelian tradition, was composed by Giles of Rome about 1276. In this work, De Formatione Corporis Humani in Utero, there are theoretical discussions of the relative contribution of the male and female parent to the gene...