![]()

STRINGED INSTRUMENTS.

PRELIMINARY.

IN this group of instruments the air-vibrations are set up by means of a stretched string or strings. There are three methods by which the strings themselves are set in motion:

1. By plucking either with the finger, as in the modern Harp, or with a mechanical instrument, such as a plectrum or quill, as in the ancient Kithara or Lyre. For musical purposes the latter group may again be divided into

(a) Instruments, such as the Mandoline, in which the strings are set in motion by a plectrum held in the player’s hand.

(b) Instruments, such as the Harpsichord or (Clavi) cembalo, in which the strings are set in motion by a quill not directly under the player’s control.

2. By striking with a hammer or hammers. This group also may be subdivided into

(a) Instruments, such as the Dulcimer,1 in which the strings are set in motion by means of hammers held in the player’s hand.

(b) Instruments, such as the Pianoforte, in which the strings are set in motion by hammers not directly and completely under the player’s control.

3. By contact with a prepared surface, which is kept in motion while in contact with the strings. This group also may be subdivided into two, each of which has had great influence on the history of music.

(a) Those instruments in which the application of the moving surface is not directly and completely under the player’s control. The best examples of this type of instrument are the obsolete Organistrum and its modern descendant, the Vielle or Hurdy-gurdy, in both of which the moving surface was a rosined wheel which pressed against the strings and was kept in motion by means of a crank.

(b) Those instruments in which the application of the moving surface is directly and completely under the player’s control. The most familiar examples of these are the old Rebecs, the Minnesinger-Fidels, the Viols, and the modern Violins, all played with a “bow.”

The development of these groups of plucked, struck, and bowed instruments is to be studied first in existing specimens; second, in theoretical and historical works, and in the surviving ancient music which was performed on them; and third, in the pictures, illuminations and carvings which are to be found scattered all over Europe.

It need not be said that, with the perishable nature of musical instruments, the first method does not take us very far back. Indeed, it is with something of a shock that one comes on an occasional orchestral player who is earning his daily bread on an instrument that was fashioned in Queen Elizabeth’s day. Such instruments actually exist, and are sometimes models of great construction; but in general one may say that, save for a stray specimen here and there, all instruments of an earlier date have vanished.

The historian is therefore compelled to rely mainly on illuminations, on carvings in stone, and on historical references. The whole of that field has been, or is being, explored with extraordinary patience and accuracy by various workers, and it is only possible here to hint at the results of their labours.2 It may be as well, however, to give a very hasty and much compressed account of the three groups of instruments mentioned above.

(1) Plucked Instruments.

This, the simplest form of stringed instruments, is also probably the most ancient. Various legends have attempted to account for its invention, but none has much value in view of the fact that even a savage who possesses a bow for the purposes of war and the chase also possesses a twanging musical instrument. The early developed type of this twanging stringed instrument is the Greek Kithara, whose shape is familiar to everyone through its constant representation in Greek statuary, bas-reliefs, and vase-paintings.

It is uncertain when and how this instrument began to develop into what we may call for the sake of shortness a Lute, that is to say, into an instrument whose strings were stretched over a vaulted resonating-box. Two facts, however, show that some changes of this sort took place at a very early date.

(1) An actual instrument of distinct Lute-type furnished with a vaulted body and with three pegs in the head was dug up at Herculaneum. Herculaneum was destroyed in a.d. 79.

(2) A four-stringed “Pandoura” is represented in a sculpture now in the Mausoleum-Room of the British Museum. This sculpture is of about Hadrian’s time, 117–138 A.D., and the instrument in question is clearly being played by plucking. It has something the appearance of a long banjo with a very small body. It differs, however, completely from a banjo in the fact that the body is vaulted like that of a Mandoline and is quite evidently a resonating-box.

It is somewhat doubtful whether these early forms continued to persist through the first centuries of the Christian era and had any true influence on the development of the mediæval Lutes. It is known for certain that the early European Lutes were based immediately on Arab forms. On the other hand, it is quite possible that these Arab forms themselves were founded on, or at any rate influenced by. the Graeco-Roman instruments.3

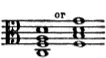

At any rate, we find that the popular instrument in Chaucers time (fourteenth century) was a boat-shaped Rebab which had probably come into Europe during the Crusades. This instrument, which was called a Cittern or Gittern,4 was held, not in violin-, but in lute-or guitar-position, and was plucked with a plectrum or sometimes with the fingers of the right hand. The Gittern had a flat back and incurved sides much like those of a modern Guitar. In this it differed completely from the pear-shaped Lute with its vaulted back. When first it came to England the Gittern was a simple instrument of four strings tuned either to

Few of these instruments survive. A fourteenth century specimen, however, restored in Queen Elizabeth’s reign and bearing the arms of the Earl of Leicester, is preserved at Warwick Castle. The Citole was a hybrid-instrument, a mixture of Gittern and Lute. It combined the flat back of the former with the pear-shape of the latter. From the Gittern-type of instrument sprang the whole Lute-family, a large and historically most important group whose services to art only ended in the seventeenth century.

There appear to have been nearly a dozen varieties of Lute distinguished from one another by their size, that is to say their pitch, and by their complexity of stringing. The double-necked Bass-Lutes, which in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries took the place of our present-day Cellos and Basses, were generally known as Theorbos. These were strung with 12, 14, or 16 strings tuned in unison-pairs like those of the modern Mandoline, and all these strings were “stopped” by the fingers of the left hand according to a method somewhat similar to that of the Guitar. On the bass-side there were from 8 to 11 “free-strings.” These were never “stopped,” that is to say, they were only employed to sound the open note of their greatest length. The largest varieties of Theorbo were the...