Chapter 1

Butenam

Knowledge

The American seafarers who came to Fiji for sandalwood and bêche-demer earned a slight share of the wealth generated but derived additional satisfaction from their time in the islands. Their unique experiences granted them a rarefied, socially elevating expertise. Returning home with fantastic stories and curiously wrought souvenirs, they became knowledge brokers whose firsthand observations shaped American perceptions of Fiji and Fiji Islanders for decades to come. They produced two kinds of knowledge, one pragmatic and logistical, the other ethnographic and ideological.

Practical knowledge made navigation safer and faster, fostered commercial networks and routines, and identified exploitable natural resources. In the mercantile culture of the early republic, this kind of knowledge was critical. Merchants advised younger generations that “knowledge is power” and that they should learn foreign languages and customs regulating the conduct of business unique to each country. They corresponded incessantly with family, friends, and strangers to ask about current prices at Batavia, Lisbon, Amsterdam, Canton, and other places around the globe, to inform associates of the availability or impossibility of obtaining certain cargos at certain ports, and to maintain channels of sociability through which news of commercial value flowed. Accurate and timely information decided the fate of financial speculations.1 This was especially so for the carrying trade, which derived profit from the differential value of things: buying low in one place, selling high somewhere else. Cultural differences in consumer tastes and demand created the large gaps in value that made the triangular trade between the United States, Fiji, and China immensely profitable.2

Ethnographic knowledge intersected with pragmatic knowledge but resulted in more than monetary rewards. By reporting on the bizarre customs of Fijians, Americans consigned its people to the opposite end of the humanity spectrum and affirmed for a larger public Americans’ cultural superiority. Americans who traveled overseas occupied a singular position from which to demonstrate intellect, initiative, and worldliness. Their esoteric knowledge attached them to the enlightenment traditions that celebrated knowledge accumulation as the epitome of civility and progress. To “know what men are and may be in a savage state” was bound up with the effort to comprehend “the human character in a civilized state” to thereby “arrive at a better knowledge of human nature in the abstract.”3 To know the other was to know oneself.

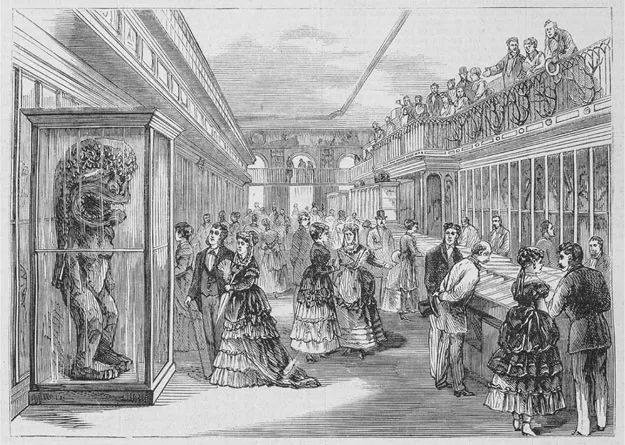

Both pragmatic and ethnographic knowledge production were fundamental to U.S. global expansion. In Fiji, American traders had to learn to navigate the archipelago’s island-studded, reef-ridden geography; what sandalwood and bêche-de-mer were, where to find them, and how to process them so as to meet the quality standards of Chinese consumers; and how to negotiate with Fijians to access their knowledge, territory, and labor. American traders could not harvest Fijian resources without Fijian help, so they needed to figure out how to communicate with Fijians, what trade items appealed to Fijian consumers, and who held power over whom. At the same time, Fijians became knowable in American popular culture as ethnographic objects, the ultimate savages. Two traders nicknamed “Butenam” exemplify the practical and ethnographic rewards awaiting Americans who entered the Fiji trade. When in 1811 Captain William Putnam Richardson of the Active came to Fiji after sandalwood, Fijians called him by his middle name because Richardson was too cumbersome to pronounce. Benjamin Vander-ford, second mate on the Active and later a captain and supercargo in the bêche-de-mer trade, inherited Richardson’s nom-de-trade.4 Richardson and Vanderford hailed from Salem, one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the United States due to its preeminence in global commerce. Salem was also home to the nation’s most renowned maritime knowledge repository, the East India Marine Society. The society encouraged its members to deposit logbooks in its library and bring back oddities for its museum. Put on display in the hodgepodge manner typical of cabinets of curiosities, these artifacts allowed for the museum’s many visitors to marvel vicariously at the primitivity of distant places (see figure 1.1). Richardson and Vanderford joined this prestigious association as soon as they were eligible and donated a large amount of Pacific material to the society’s collections.5

Figure 1.1. This magazine illustration captures the contrast between the gentility of museum goers and the exoticism of the East India Marine Society artifacts exhibited in Salem. A carved wooden god acquired in Hawai‘i is visible in the display case on the left. Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 4 Sept. 1869, 393. Courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society.

As one of the last Pacific island archipelagos visited by Europeans, Fiji was a cipher on maps of the world when the sandalwood trade started in 1804. Over the next fifty years, a more detailed picture of Fiji emerged, much of it produced by Americans whose jobs took them there. Before the sandalwood boom, Americans knew only two things about Fiji: it was northwest of the Tonga Islands, and Fijians were ferocious cannibals. These inklings came from scant, secondhand remarks in the writings of British explorers.6

Captain James Cook’s famous voyages of exploration included a sighting of Fiji and comments about Fijian people. In 1774, on his second voyage to the Pacific, he reached Vatoa on the archipelago’s eastern edge but saw its inhabitants only from a distance. He named it “Turtle Island” and noted its location. At Tonga three years later, while on his third voyage, Cook heard of a large island to the west called “Feejee,” probably a reference to Viti Levu, and met Fijians, whom he described as “a full shade darker” than Tongans and “addicted, like those of New Zealand, of eating their enemies, whom they kill in battle.” Cook further claimed that Fijians were “much respected” in Tonga for the “cruel manner of their nation’s going to war” and their ingeniously crafted clubs, spears, tapa bark cloth (masi in Fiji), mats, and pottery.7 Cook influenced other travelers’ expectations. Captain James Wilson of the Duff, at Tonga in the late 1790s to drop off London Missionary Society fieldworkers, cribbed from Cook nearly verbatim in his account of the Duff’s voyage, describing Fijians as “cannibals of a fierce disposition.” He imagined them “dancing round us, while we were roasted on large fires.”8 Thus the earliest images of Fiji to circulate in Europe and the United States fixated on cannibalism.

Other seafarers sailing through the archipelago on the way to somewhere else filled in more specifics on the location and extent of “Feejee” as it appeared on early charts of the Pacific.9 William Bligh sighted northern Viti Levu and the Yasawa group as he steered the Bounty launch from Tonga to Timor after the 1789 mutiny by members of his crew.10 On a second voyage in 1792, this time successfully transporting breadfruit from Tahiti to the Caribbean, Bligh more deliberately marked islands passed on his course from Tonga through southeastern Fiji and claimed “Bligh’s Islands” as his discovery.11 Americans, too, recorded islands spotted while traversing the archipelago. On the Ann & Hope— a Providence, Rhode Island, trader en route to China—someone charted several islands and later publicized their geographic coordinates in American newspapers.12 The impact was moot, however, since no one in the United States had any reason to go to Fiji.

The China trade made Fiji an American destination. Chinese luxury goods had been imported into the British North American colonies since the seventeenth century, but the British East India Company’s monopoly thwarted colonists’ ambitions to conduct their own trade.13 Immediately after the revolutionary war, in 1784, the Empress of China departed New York, the Grand Turk from Salem two years later, and every year thereafter several vessels from Boston, Providence, Philadelphia, and other eastern port cities. American ships carried the medicinal herb ginseng and Spanish dollars around the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn, returning home flush with tea, silk, and porcelain wares.14 Because the Chinese had little interest in what Americans had to offer, merchants set about to discover what else besides ginseng and dollars the Chinese might want. They sent ships to North America’s Northwest Coast to trade with Indians for sea otter pelts and other ships southward to slaughter seals. Slashing and burning through one commodity after another, they happened upon Pacific sandalwood.15

The essential oils found in the slow-growing heartwood of the sandal-wood tree exude a heady, ethereal aroma. Pacific peoples favored sandal-wood as a scent and soaked scrapings of it into coconut oil. Fijians valued it most as a trade item, and before papalagi came in search of it, they regularly exchanged it with Tongans for stingray barbs, tapa, and other items of Tongan manufacture. Some sandalwood grew in Tonga but not very well. The Chinese also treasured sandalwood. Americans in China remarked on the sandalwood “Joss” or “Josh” sticks burned before altars in religious rites and the fans, boxes, and chests carved from it. But unlike ginseng, sandal-wood did not grow in North America and so was not feasible as an American export. The highest quality sandalwood came from India and arrived in China on British East India Company ships. Pacific sandalwood was not as fragrant as Indian sandalwood, but the species that grew in Fiji, santa-lum yasi, was one of the more aromatic. Small cargos of Pacific sandalwood dribbled into China’s foreign trading entrepôt at Canton in the 1790s, but it was not until the American sailor Oliver Slater noticed extensive sandalwood groves in Fiji in 1804 that foreign ships began large-scale cutting of Pacific sandalwood. The rush began at Fiji, spread to the Marquesas in the 1810s, lasted at Hawai‘i into the early 1820s, and ended at the New Hebrides and New Caledonia in the 1830s and 1840s.16

Little is known about Slater and his ship, the Argo, which wrecked on a reef while sailing through Fiji around 1800. He found refuge among Fijians at Bua Bay on Vanua Levu. Two years later, El Plumier, a former Spanish vessel owned by Sydney merchants, pulled into Bua Bay to make repairs and transported Slater to Manila. He then took a Manila-registered ship named the Fair American, to Port Jackson, the harbor of Sydney, New South Wales. At that time mainly a penal colony for British malfeasants, Sydney was emerging as a shipping hub for Pacific commerce, and a Sydney firm run by former convicts—Lord, Kable, and Underwood—responded to Slater’s report of Fijian sandalwood by sending him back to Bua Bay on their schooner Marcia in September 1804. The Marcia soon returned with fifteen tons, the first cargo of sandalwood collected at Fiji bound for Chinese markets.17

Meanwhile a sandalwood frenzy erupted at Sydney. British vessels licensed through the East India Company to enter the port of Canton and colonial vessels that operated out of Sydney left for the islands. The Americans involved early on were sealers in the China trade who happened to be anchored at Port Jackson, replenishing food stores and waiting out harsh winter weather on southern sealing grounds. The Fair American, the ship that had brought Slater to Sydney, and the Union, a sealing brig owned by New York merchants Edmund Fanning and Willet Coles, stocked up on scrap iron and trinkets and left for Bua Bay. The Union thwarted an attack by islanders at Tonga, retreated to Sydney, and departed again for Fiji, but upon arriving in the Fiji group, shipwrecked off Koro Island. Its crew and passengers were never heard from again.18 The Fair American apparently loaded up on sandalwood and sailed to Manila or Canton.19 The following year, Captain Peter Chase of the Nantucket sealer Criterion collaborated with Sydney investors and, with Slater in company as guide and interpreter, made a highly profitable voyage to Fiji and Canton.20

When the news reached merchants in the United States, they added Fijian sandalwood to the lengthening roster of items C...