- 352 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Egyptian Mythology

About this book

The complexities of Egyptian mythology — its gods, sun and animal worship, myths, and magical practices — are explored. The development of religious doctrines, as portrayed in art and in literature, also receives a close inspection. Magnificently illustrated, the text contains 232 figures that clarify ancient beliefs and customs.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Egyptian Mythology by F. Max Müller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Middle Eastern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I

THE LOCAL GODS

ANIMISM is a very wide-spread form. of primitive religion. It has no gods in the sense of the advanced pagan religions; it only believes that earth and heaven are filled by countless spirits, either sedentary or wandering. These spirits can make their earthly abode in men, animals, or plants, or any object that may be remarkable for size or form. As soon as man, in his fear of these primitive deities, tries to placate them by sacrifices, they develop into tutelary spirits and fetishes, and then into gods. Some scholars claim that all religions have sprung from a primitive animism. Whether this be true or not, such an origin fits the primitive Egyptian religion especially well and explains its endless and confused pantheon. The Egyptians of the historical period tell us that every part of the world is filled by gods, an assertion which in our days has often been misinterpreted as if those gods were cosmic, and as though a primitive kind of pantheism underlay these statements. Yet the gods who lived, for instance, in the water, like the crocodile Sobk, the hippopotamus-deity Êpet, etc., did not represent this element; for the most part they merely inhabited a stretch of water. We find that in general the great majority of the old local gods defy all cosmic explanation: they still betray that once they were nothing but local spirits whose realm must primarily have been extremely limited. In the beginning there may have been a tendency to assume tutelary spirits for every tree or rock of unusual size or form or for every house and field, such spirits being worshipped in the first case in the form of the sacred object itself in which they abode, and in the latter case being embodied in some striking object in the locality or in some remarkable animal which chanced to frequent the place. Many of these tutelary spirits never developed into real gods, i. e. they never received a regular cult. The transitional stage appears in such instances as when, according to certain Theban wall-paintings, the harvesters working in a field deposited a small part of their food as an offering to a tree which dominated that field, i. e. for the genius inhabiting the tree; or when they fed a serpent discovered on the field, supposing it to be more than an ordinary creature.1 This serpent might disappear and yet be remembered in the place, which might in consequence remain sacred forever; perhaps the picture of its feeding may thus be interpreted as meaning that even then the offering was merely in recollection of the former appearance of a local spirit in serpent form.

Another clear illustration of primitive animism surviving in historic times is furnished by an old fragment of a tale in a papyrus of the museum of Berlin. Shepherds discover “a goddess” hiding herself in a thicket along the river-bank. They flee in fright and call the wise old chief shepherd, who by magic formulae expels her from her lair. Unfortunately the papyrus breaks off when the goddess “came forth with terrible appearance,” but we can again see how low the term “god” remained in the Pyramid Age and later.

Such rudimentary gods, however, did not play any part in the religion of the historic age. Only those of them that attracted wider attention than usual and whose worship expanded from the family to the village would later be called gods. We must, nevertheless, bear in mind that a theoretical distinction could scarcely be drawn between such spirits or “souls” (baiu) which enjoyed no formal or regular cult and the gods recognized by regular offerings, just as there was no real difference between the small village deity whose shrine was a little hut of straw and the “great god” who had a stately temple, numerous priests, and rich sacrifices. If we had full information about Egyptian life, we certainly should be able to trace the development by which a spirit or fetish which originally protected only the property of a single peasant gradually advanced to the position of the village god, and consequently, by the growth of that village or by its political success, became at length a “great god” who ruled first over a city and next over the whole county dominated by that city, and who then was finally worshipped throughout Egypt. As we shall see, the latter step can be observed repeatedly; but the first progress of a “spirit” or “soul” toward regular worship as a full god 2 can never be traced in the inscriptions. Indeed, this process of deification must have been quite infrequent in historic times, since, as we have already seen, only the deities dating from the days of the ancestors could find sufficient recognition. In a simpler age this development from a spirit to a god may have been much easier. In the historic period we see, rather, the opposite process; the great divinities draw all worship and sacrifices to their shrines and thus cause many a local god to be neglected, so that he survives only in magic, etc., or sinks into complete oblivion. In some instances the cult of such a divinity and the existence of its priesthood were saved by association with a powerful deity, who would receive his humbler colleague into his temple as his wife or child; but in many instances even a god of the highest rank would tolerate an insignificant rival cult in the same city, sometimes as the protector of a special quarter or suburb.

Originally the capital of each of the forty-two nomes, or counties, of Egypt seems to have been the seat of a special great divinity or of a group of gods, who were the masters and the patrons of that county; and many of these nomes maintained the worship of their original deity until the latest period. The priests in his local temple used to extol their patron as though he was the only god or was at least the supreme divinity; later they often attributed to him the government of all nature and even the creation of the whole world, as well as the most important cosmic functions, especially, in every possible instance, those of a solar character; and they were not at all disturbed by the fact that a neighbouring nome claimed exactly the same position for its own patron. To us it must seem strange that under these conditions no rivalry between the gods or their priests is manifest in the inscriptions. To explain this strange isolation of local religion it is generally assumed that in prehistoric times each of these nomes was a tribal organization or petty kingdom, and that the later prominence given to their divine patron or patrons was a survival of that primitive political independence, since every ancient Oriental state possessed its national god and worshipped him in a way which often approximated henotheism. 3 Yet the quasi-henotheistic worship which was given to the patron of these forty-two petty capitals recurred in connexion with the various local gods of other towns in the same nome, where even the chief patron of the nome in question was relegated to the second or third rank in favour of the local idol. This was carried to such an extent that every Egyptian was expected to render worship primarily to his “city-god” (or gods), whatever the character of this divinity might be. Since each of the larger settlements thus worshipped its local tutelary spirit or deity without determining his precise relation to the gods of other communities, we may with great probability assume that in the primitive period the village god preceded the town god, and that the god of the hamlet and of the family were not unknown. At that early day the forces of nature appear to have received no worship whatever. Such conditions are explicable only from the point of view of animism.4 This agrees also with the tendency to seek the gods preferably in animal form, and with the strange, fetish-like objects in which other divinities were represented.

Numerous as the traces of animistic, local henotheism are, the exclusive worship of its local spirit by each settlement cannot have existed very long. In a country which never was favourable to individualism the family spirit could not compete with the patron of the community; and accordingly, when government on a larger scale was established, in innumerable places the local divinity soon had to yield to the god of a town which was greater in size or in political importance. We can frequently observe how a chief, making himself master of Egypt, or of a major part of it, advanced his city god above all similar divinities of the Egyptian pantheon, as when, for instance, the obscure town of Thebes, suddenly becoming the capital of all Egypt, gained for her local god, Amon, the chief position within the Egyptian pantheon, so that he was called master of the whole world. The respect due to the special patron of the king and his ancestors, the rich cult with which that patron was honoured by the new dynasty, and the officials proceeding from the king’s native place and court to other towns soon spread the worship of Pharaoh’s special god through the whole kingdom, so that he was not merely given worship at the side of the local deities, but often supplanted them, and was even able to take the place of ancient patrons of the nomes. Thus we find, for instance, Khnûm as god of the first and eleventh nomes; Ḥat-ḥôr, whose worship originally spread only in Middle Egypt (the sixth, seventh, and tenth nomes), also in the northernmost of the Upper Egyptian nomes (the twenty-second) and in one Lower Egyptian nome (the third); while Amon of Thebes, who, as we have just seen, had come into prominence only after 2000 B.C., reigned later in no less than four nomes of the Delta. This latter example is due to the exceptional duration of the position of Thebes as the capital, which was uninterrupted from 2000 to 1800 and from 1600 to 1100 B.C.; yet to the mind of the conservative Egyptians even this long predominance of the Theban gods could not effect a thorough codification of religious belief in favour of these gods, nor could it dethrone more than a part of the local deities.

As we have already said, the difficulty of maintaining separate cults, combined with other reasons, led the priests at a very early time to group several divinities together in one temple as a divine family, usually in a triad of father, mother, and son; 5 in rarer instances a god might have two wives (as at Elephantine, and sometimes at Thebes);6 in the case of a goddess who was too prominent to be satisfied with the second place as wife of a god, she was associated with a lesser male divinity as her son (as at Denderah). We may assume that all these groups were formed by gods which originally were neighbours. The development of the ennead (perhaps a triple triad in source) is obviously much later (see pp. 215—16).

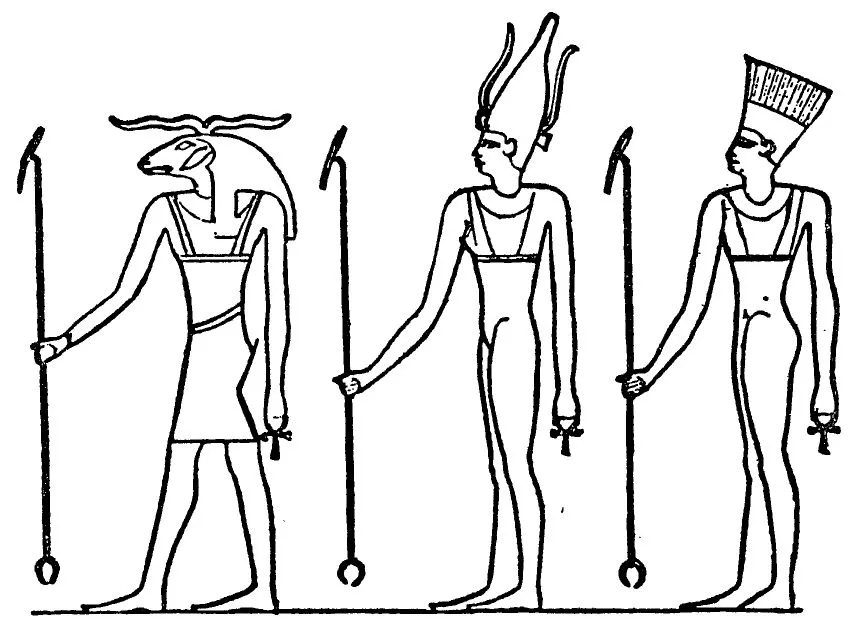

FIG. 1. THE TRIAD OF ELEPHANTINE: KHNÛM, SATET, AND ‘ANUQET

As long as no cosmic rôle was attributed to the local gods, little mythology could be attached to their personality; even a deity so widely worshipped as the crocodile Sobk, for example, does not exhibit a single mythological trait. Of most gods we know no myths, an ignorance which is not due to accidental loss of information, as some Egyptologists thought, but to the fact that the deities in question really possessed little or no mythology. The only local divinities capable of mythological life, therefore, were those that were connected with the cycle of the sun or of Osiris.

A possible trace of primitive simplicity may be seen in the fact that some gods have, properly speaking, no names, but are called after their place of worship. Thus, the designation of the cat-shaped goddess Ubastet means only “the One of the City Ubaset,” as though she had long been worshipped there without a real name, being called, perhaps, simply “the goddess”; and, again, the god Khent(i)-amentiu (“the One Before the Westerners,” i.e. the dead),7 who was originally a jackal (?), seems to have received his appellation simply from the location of his shrine near the necropolis in the west of This. These instances, however, admit of other explanations —an earlier name may have become obsolete;8 or a case of local differentiation may be assumed in special places, as when the jackal-god Khent(i)-amentiu seems to be only a local form of Up-uaut (Ophoïs). Names like that of the bird-headed god, “the One Under his Castor Oil[?] Bush” (beq), give us the impression of being very primitive.9 Differentiation of a divinity into two or more personalities according to his various centres of worship occurs, it is true; but, except for very rare cases like the prehistoric differentiation of Mîn and Amon, it has no radical effect. In instances known from the historic period it is extremely seldom that a form thus discriminated evokes a new divine name; the Horus and Ḥat-ḥôr of a special place usually remain Horus and Ḥat-ḥôr, so that such differentiations cannot have developed the profuse polytheism from a simpler system. On the contrary, it must be questioned whether even as early an identification as, e. g., of the winged disk Beḥdeti (“the One of Beḥdet” [the modern Edfu]) with Horus as a local form was original. In this instance the vague name seems to imply that the identification with Horus was still felt to be secondary.

Thus we are always confronted with the result that, the nearer we approach to the original condition of Egypt, the more we find its religion to be an endless and unsystematic polytheism which betrays an originally animistic basis, as described above. The whole difficulty of understanding the religion of the historic period lies in the fact that it always hovered between that primitive stage and the more advanced type, the cosmic conception of the gods, in a very confusing way, such as we scarcely find in any other national religion. In other words, the peculiar value of the ancient Egyptian religion is that it forms the clearest case of transition from the views of the most primitive tribes of mankind to those of the next higher religious development, as represented especially in the religion of Babylonia.

FIG. 2. SOME GODS OF PREHISTORIC EGYPT WHOSE WORSHIP LATER WAS LOST

(a), (b) A bearded deity much used as an amulet; (c), (d) a double bull (Khônsu?); (e) an unknown bull-god; (f) a dwarf divinity(?) similar to Sokari, but found far in the south.

CHAPTER II

THE WORSHIP OF THE SUN

TAKING animism as the basis of the earliest stage of Egyptian religion, we must assume that the principal cosmic forces were easily personified and considered as divine. A nation which discovers divine spirits in every remarkable tree or rock will find them even more readily in the sun, the moon, the stars, and the like. But though the earliest Egyptians may have done this, and perhaps may even have admitted that these cosmic spirits were great gods, at first they seem to have had no more thought of giving them offerings than is entertained by many primitive peoples in the animistic stage of religion who attach few rel...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Table of Figures

- Dedication

- AUTHOR’S PREFACE

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER I - THE LOCAL GODS

- CHAPTER II - THE WORSHIP OF THE SUN

- CHAPTER III - OTHER GODS CONNECTED WITH NATURE

- CHAPTER IV - SOME COSMIC AND COSMOGONIC MYTHS

- CHAPTER V - THE OSIRIAN CYCLE

- CHAPTER VI - SOME TEXTS REFERRING TO OSIRIS-MYTHS

- CHAPTER VII - THE OTHER PRINCIPAL GODS

- CHAPTER VIII - FOREIGN GODS

- CHAPTER IX - WORSHIP OF ANIMALS AND MEN

- CHAPTER X - LIFE AFTER DEATH

- CHAPTER XI - ETHICS AND CULT

- CHAPTER XII - MAGIC

- CHAPTER XIII - DEVELOPMENT AND PROPAGATION OF EGYPTIAN RELIGION

- NOTES - EGYPTIAN

- BIBLIOGRAPHY - EGYPTIAN