eBook - ePub

As Seen on TV

The Visual Culture of Everyday Life in the 1950s

Karal Ann Marling

This is a test

Share book

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

As Seen on TV

The Visual Culture of Everyday Life in the 1950s

Karal Ann Marling

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

America in the 1950s: the world was not so much a stage as a setpiece for TV, the new national phenomenon. It was a time when how things looked--and how we looked--mattered, a decade of design that comes to vibrant life in As Seen on TV. From the painting-by-numbers fad to the public fascination with the First Lady's apparel to the television sensation of Elvis Presley to the sculptural refinement of the automobile, Marling explores what Americans saw and what they looked for with a gaze newly trained by TV. A study in style, in material culture, in art history at eye level, this book shows us as never before those artful everyday objects that stood for American life in the 1950s, as seen on TV.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is As Seen on TV an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access As Seen on TV by Karal Ann Marling in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Mamie Eisenhower’s New Look

In December of 1946, according to legend, Christian Dior retreated to the chateau of a friend in Fontainebleau. Fifteen days later he emerged with the sketches for his première collection, his so-called Corolle Line. “We were leaving a period of war, of uniforms, of soldier-women with shoulders like boxers,” he later mused. “I turned them into flowers, with soft shoulders, blooming bosoms, waists slim as vine stems, and skirts opening up like blossoms.” The world press saw Dior’s designs for the first time in Paris on February 12, 1947—and came away enchanted. After seven long years of wartime make-do, rationing, and stringent rules governing the amount of fabric permissible in a given garment, after seven years of skimpy, asexual suits and silence from the great French couturiers, fashion and femininity were back at last. Dior’s suits were sensuous, positively luxurious—gloriously full in the skirt, and topped off with great, extravagant cartwheel hats. Nipped at the waist, rounded at the hips and bustline, sloping gracefully through the shoulder, they defined the body’s every womanly, viva la difference contour. The silhouette was so different, so utterly novel that Life magazine christened it “The New Look.”1

The New Look. It was a phrase like “The Middle Ages” or “The Four Freedoms.” It signified an entity, an institution to be reckoned with, permanent, significant. And Dior’s line was all those things—and more. Suddenly, peplums and petticoats were everywhere. Hemlines plunged. Women used to piecing together an outfit from a hand-me-down dress, an old jacket, and a newish hat learned to covet ensembles in which shoes, bags, and even perfume were carefully coordinated by a designer to achieve an artful totality. An American woman returning from China after a year abroad first encountered the long skirts and unpadded shoulders in Calcutta and thought they “looked like something out of a masquerade party,” but by the time she reached New York she “felt conspicuous” in her out-of-date clothes.2

Dior’s New Look of 1947, according to Harper’s Bazaar. This was the style that set the tone for the "look" of the 1950s in the United States.

Everybody was wearing or copying the New Look, it seemed, and the renascent fashion business had become a matter of churning out Paris knockoffs as quickly as possible. “If there could be a composite, mythical woman dressed by a mythical, composite couturier,” Vogue opined, “she would probably wear her skirt about fourteen inches from the floor” and it would be modeled on a flower. By 1952 or so, variants had appeared. Jacques Fath went in for pencil-slim skirts topped off by exuberant, flower-like jackets, for example, and Dior himself eventually renounced the big hat in favor of sleek little heads that did not distract attention from the sculptural qualities of his models. For make no mistake about it: the New Look was a form of living sculpture, created by ingenious corsetry, inspired design, and an intricate dressmaking technique that amounted to a kind of body engineering.3

The molded, hourglass shape was achieved through a variety of means: padding hidden in the lining of jackets to accentuate the swelling of the hips; boning, stays, or other constricting devices built into waistlines; and an internal framework composed of layers of tulle, organza, silk pongee, and a new “miracle fabric”—nylon. A well-wrought Dior, it was said, could stand up by itself in a corner, after the wearer had gone to bed. It could be argued, of course, that the woman inside was irrelevant to the dress, that she was the victim of fashion, enslaved and oppressed by her own dinner gown. Edmund Bergler, an American psychoanalyst of the 1950s, dismissed the fashion industry as a “gigantic unconscious hoax” perpetrated on women by homosexual men who wanted to make them look ridiculous.4 The New Look was just one more sign of the rampant sexual malaise of the times.

Christian Dior saw things differently. The women tottering precariously about on the high heels that completed the Corolle costume were rediscovering the grace of the dance, he insisted, while his ankle-grazing hemlines had “restored all its former mystery to the leg.” Husbands weren’t so sure, though. Who was this Frenchman, this Dior character, to cover up the female leg? The leg which, thanks to Betty Grable’s famous G.I. pinup, had become as American as baseball and Mom’s apple pie! The New Look “shows everything you want to hide and hides everything you want to show,” their wives complained. On aesthetic grounds alone, a Little Below the Knee Club founded in Dallas (where pickets were thrown up around an award ceremony honoring the great Dior) attracted a nationwide membership. “The Alamo fell but our hemlines will not!” cried the fashion holdouts.5

Others, including a League of Broke Husbands organized in Georgia, objected to the whole concept of style, obsolescence, and change. In England, as shortages persisted and Princess Elizabeth chose calf-length skirts for her trousseau, New Look wardrobes became the subject of serious political debate on grounds of waste, unwholesome “over sexiness,” and ideology. The costume historian James Laver, writing in British Vogue in 1944, had described a “fashion of collaborators” then being worn in Occupied Paris. The Germans went down to defeat but this Küche und Kinder style—frilly, wasp-waisted, romantic, and reactionary—seemed to have won the war for the hearts and minds of the well-dressed victors. In The Second Sex, published in Paris in 1949, at the high water mark of Dior’s influence, Simone de Beauvoir toyed with the notion of fashionable “elegance as bondage.”6

The New Look has never really stopped being controversial. Fashion experts still squabble over Dior’s authorship of the style. Weren’t Scarlett O’Hara’s laced corsets and crinolines in the 1939 movie Gone With the Wind as “new look” as anything turned out by the House of Dior? Hadn’t the so-called American Look designers, like Claire McCardell, introduced natural shoulders, fuller skirts, and cinch belts back in 1946? Others, less concerned with issues of primacy and more interested in meaning, recoil from what the designer and fashion photographer Cecil Beaton called the “wanton fantasy” of the New Look—an artificial, manufactured woman whose anatomical differences were exaggerated to conform to the sexual dimorphism of the 40s and 50s. Was a woman who stuffed herself into a girdle and high heels a woman at all, by the hard-body, in-your-face standards of the 1990s? Wasn’t she some form of sexual chattel? A piece of pretty, consumer-culture, top-of-the-TV-set bric-a-brac?7

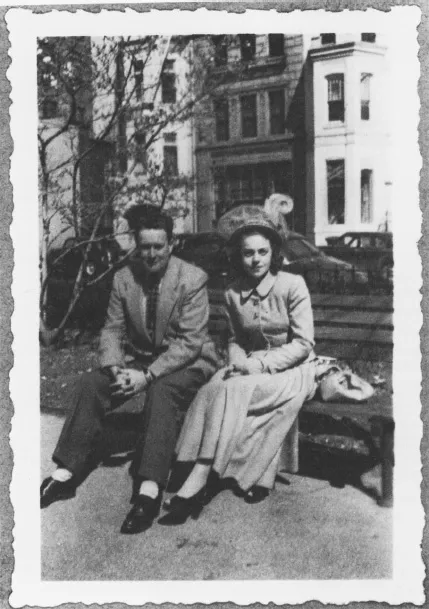

My parents on a second honeymoon in Washington, D.C., circa 1948. My mother and her mother made the New Look outfit: long, full skirt; fitted peplum jacket; wild hat.

She was, without question, artful, and the harbinger of what one design specialist dubs “a radical shift in aesthetic” which would, by the middle of the 1950s, transform everything from bric-a-brac and automobiles to cakes, plastic cups and saucers, high-style furniture, and off-the-rack department store outfits.8 The postwar aesthetic asserted the importance of deliberate artfulness, of close attention to matters of color, line, and form. The Diors of the world readily achieved celebrity status in such an atmosphere, but so did Harley Earl (chief stylist for General Motors), Russel Wright (creator of American Modern dinnerware), Charles Eames (designer of spindly-legged, full-bodied chairs made of new high-tech materials), and Jackson Pollock (Abstract Expressionist painter). One strain of 50s design was organic—a synonym for curvilinear, volumetric, vaguely bosomy shapes. The New Look was organic to a fault but so were the lazy, sexy sag of a Wright cream pitcher and the tumescence on the back fender of the Cadillac (1948–ca. 1953) that would shortly become a full-fledged tail fin. A second strain was two-dimensional, textural, and richly patterned, like a vintage Pollock. It was colorful, obtrusive, and lavish. A little too much, perhaps. Like yards of figured peau de soie with dyed-to-match gloves and shoes.

The design critic Thomas Hine uses the term “populuxe”—that is, glitz and glitter for the masses—to describe the consumer products of the postwar era, including the retail versions of the New Look. He’s right about the obsession with the outsides of things. The kitchen-matching finish (“New Colorama Styling!”) of the Frigidaire electric range for 1954, for instance, probably weighed as heavily in customer buying decisions as any technical features described in the small print. But the new stove also came with a “Visi-door,” allowing the housewife to look inside without opening the oven.9 Cooking as television. The very construction of the artifact makes it clear that looking and viewing were central acts of consciousness. In the most fundamental of ways, the New Look is about looking, too—about distinctive forms, eye-catching patterns and textures, and attractive colors; about looking at people and their clothes and being looked at in turn; about thinking about looking. Looking: not the judgmental “gaze” of contemporary feminist theory, but something more like a scrupulous, pleasurable regard for both shape and surface.10 In this respect, there is something post-literate about the 50s. And the association of a diagnostic habit of vision with sensual enjoyment makes the New Look all the harder to talk about. Or rather, it is all too easy to dismiss as trivial and superficial the lives of those who looked for their own reflections in the era’s glittering surfaces.

Most modern design in the early 1950s resembled a woman wearing a New Look dress. Even lamps had waistlines, hips, busts, and slender legs.

Applied to the female body, the principles of the New Look exuded a palpable optimism. If its basic shape could be changed, so could the human condition or, at the very least, the life of the lady in the son-of-Dior suit. Things were always perfectible, just as form—one’s own included—was invariably improved by the complex play of pattern against contour and volume. So the old rules of finality no longer pertained. In the design ethos of the New Look, everything was always brand, spanking new.

To understand the New Look in this way suggests that people and artifacts engage in a complex sensual dialectic. Women may or may not have been the pawns of manufacturers engaged in a conspiracy to keep them homebound (and busily breeding more consumers) by a sort of invalidism of fashion: heels too high for walking, dresses too confining for real freedom of movement.11 But they did experience actual physical changes—a corporeal transformation—within their own persons when they put on New Look clothes. They felt a constant pressure at the waistline, a flutter of drapery around the legs, the friction of flesh and close-fitting fabric across the breasts. With the torso both contained and sensitized by the cut of the garment, the movement of the leg became, by sheer contrast, a significant gesture.

“A garment that squeezes the testicles makes a man think differently,” observes Umberto Eco in his famous essay on wearing jeans. By pinching and poking him in unfamiliar ways, his clothing drove Eco to an “epidermic self-awareness” of a charged relationship between self, garment, and society—or precisely the aesthetic of the New Look. He sees nothing of value in that relationship, however, concluding instead on a note of pity for women, perpetually enslaved by fashion and forced to “live for the exterior.” But the autoerotic aspects of the Dior ensemble are clear enough to women who wore New Look styles. “High heels and corsets provide intense kinesthetic stimulation for women,” writes Beatrice Faust, “appealing to the sense of touch by extending more than skin deep. These frivolous accessories are not just visual stimuli for men; they are also tactile stimuli for women.” The frivolous externals of fashion may themselves trigger deeply internalized consequences.12

Because externals are the usual bases of advertising, the notion that style and appearances may actually matter is distressing to many critics of American mass culture weaned on Vance Packard’s 1957 expose of Madison Avenue.13 Frederic Jameson traces the beginnings of the postmodern malaise to the point just after World War II when the empty blandishments of advertising accelerated the already “rapid rhythm of fashion and styling changes.” By virtue of its intimate proximity with the body, however, fashion also functions as an extension of personality, a medium through which autobiographical statements (true or false ones) are made manifest. “Clothes are a sort of theatre where the leading player—the self—is torn between function and decoration, protection and assertion, concealment and display,” posits the British design critic Stephen Bayley. In fitting rooms all across America, women twirling before mirrors in their first New Look skirts understood the dynamic perfectly. Pretty clothes not only enhanced the self; the theater of fashion also allowed the wearer to explore multiple identities and potential starring roles. In her satiric memoir of suburban life in the 1950s, Margaret Halsey described a shopping excursion to the city that changed a dutiful housewife into a sex goddess the moment she tried on “a silk print which, worn with very high heels and my hair in a French roll, makes me look properl...