![]()

1

The Historical Foundations of East Asian Development

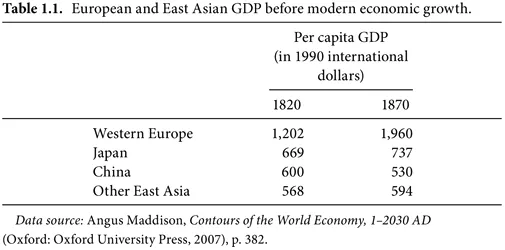

One cannot understand economic development in East and Southeast Asia unless one also understands the historical foundations on which contemporary development efforts are built. A feature that all of the countries in the region have in common, those that succeeded in achieving sustained periods of economic growth and those that did not, is that they began their development efforts at similar very low levels of per capita income. Nations and colonies, of course, did not have statistical bureaus that estimated GDP in the nineteenth century—the concept of GDP was not even invented until the 1930s, but various attempts were made to construct GDP per capita in Asia in the nineteenth century.1 The best known estimates are those of Angus Maddison, reported in Table 1.1. They indicate that per capita income in East Asia was roughly half of that in western Europe in the early nineteenth century, when most European countries had yet to begin to achieve sustained modern economic growth.

When one moves beyond per capita income similarities in the region, however, there are significant differences among the economies. In broad-brush terms, these differences break down between the economies of Northeast Asia and Southeast Asia, although there are significant differences within the two regions as well. To begin with, most Southeast Asian countries were colonies of European powers (except for Thailand) whereas much of Northeast Asia was never colonized, except for Japan’s brief colonial foray into Korea and Taiwan in the first half of the twentieth century. Northeast Asian countries all shared a tradition based to an important degree on Confucian values whereas most of Southeast Asia did not, although again there are exceptions (Vietnam, and the Chinese minority populations in Southeast Asia). This cultural difference accounts in part for another large difference, the emphasis on education even in premodern times in Northeast Asia, in contrast to the lack of much formal education in most of Southeast Asia prior to modern times. Northeast Asia is entirely in the temperate zone while Southeast Asia is entirely in the tropics. Partly because of this geographical difference but also because of differences in governance, Northeast Asia was very densely populated while much of Southeast Asia in premodern times (with the notable exception of the island of Java) was not.

The remainder of this discussion will be devoted first to the differing nature of governance in the region, followed by the differences in education levels and in population density, and ending with a brief discussion of the degree to which development of local commercial and industrial businesses in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries laid a foundation that modernizing governments could later build on.

Experience with Self-Governance

The first thing to note about governance in the region is the fact that China and Japan were self-governing, unified states for hundreds or thousands of years, depending on how one measures unity. Tokugawa Japan unified the warring feudal states of Japan in the early seventeenth century, and the existence of a single emperor for the whole country goes far back before that, although effective rule was located in feudal domains called han. China, first unified in 221 BC, was divided mostly by northern invaders from time to time in several subsequent centuries but then was unified under Han Chinese rule in 1368 and has been unified ever since, except for periods of civil war. Korea unified three states within its current borders for the first time in the seventh century, and except for invasions by Mongols and Japanese and direct Japanese colonial rule from 1905 (formally from 1910), through 1945 it was governed by Koreans as a unified state, until its division by the allied powers at the end of World War II in 1945, after which it was self-governing as two separate states. Taiwan was ruled by the Japanese from 1895 through 1945 and Hong Kong by the British from 1841 through 1997, but these economies were otherwise part of China and China’s governance traditions. British influence on the way Hong Kong is governed to this day was and is profound, and Japanese influence and the fact that Taiwan has been self-governing since 1949 gives the two territories a substantially different experience from the rest of China but one that today is still rooted in large part in Chinese culture.

Parts of Southeast Asia were also self-governing throughout most of their history, but other parts were the creation of European colonialism. Thailand has been self-governed by the Thai people for centuries, although its borders fluctuated substantially depending on success or failure in wars with Burma and the Khmer. The Burmese ruled Burma during these same centuries until the British, after victory in the Anglo-Burmese wars (1824–1852), made Burma a province of India and ruled it until it regained independence in 1948. Vietnam was ruled by China for a millennium but gained its independence from China a thousand years ago and was self-governing until the French took it over (and Cambodia and Laos) in stages, beginning in 1858 and continuing through 1887, when French Indo-China was formed. French rule ended in 1954 after the battle of Dien Bien Phu. Colonial rule in Burma and Vietnam, therefore, lasted two to three times longer than the Japanese rule of Korea and Taiwan. Neither French nor British political institutions survived for long after independence was restored, however. A coup in Burma in 1962 brought a military government to power, where it remains to this day,2 and the Vietnamese forces under Ho Chi Minh set up a single-party Communist dictatorship, first in the north in 1954 and then in the rest of the country in 1975, a form of government that had more in common with the Vietnamese monarchies of the past than with anything that could be attributed to French traditions (other than the authoritarian nature of French colonial rule).

Finally there was Spanish rule (followed by a half century of American rule) of the Philippines; Dutch rule of what became the nation of Indonesia, which began in the early seventeenth century and ended in 1949 with Dutch recognition of Indonesian independence; and British rule of what today is Malaysia and Singapore, which began in key parts of the region (notably Penang and Singapore) in the early nineteenth century. Prior to being taken over by the European colonial powers, these areas of Southeast Asia were ruled by a number of kingdoms or sultanates whose territories and populations shifted with the tides of political-military contests between them. Starting with indirect rule through these kingdoms, the colonial powers gradually consolidated their control, leaving very limited power to the sultans in the British-controlled areas, even less to the Jogyakarta sultans, and nothing at all to the indigenous rulers of the area that is now the Philippines.

The reason for this very brief recitation of history is to make a simple point. Governance in Northeast Asia, with the brief interlude of Japanese rule of Korea and Taiwan, was by local rulers working through indigenous institutions. Whether working in the interests of the local populations or against them, whether competent or incompetent, the experience gained was by local people governing their own people. Furthermore, in Northeast Asia the people in each country shared a common culture and saw themselves first and foremost as part of that culture, whether Han Chinese, Korean, or Japanese. Unity of these states within reasonably well-recognized borders was thus the norm. Invasions and civil wars occurred from time to time, but no breakup of these countries into various parts was sustainable. The tension caused by the division of the Korean people into two separate states is simply a contemporary manifestation of this powerful drive to match a shared culture with shared rule. On a more positive note, none of the rulers of these states has had to contend with major efforts backed by a large part of the population to break away and form a separate state, as happened to Pakistan and Ethiopia and has led to countless civil wars and attempts to break away elsewhere, particularly in Africa.3

Those with political aspirations in Northeast Asia thus had the opportunity to test their governance skills if they could pass the necessary examinations (imperial China and to a degree Korea), had the right pedigree and skills (pre-Meiji Japan), or were involved in a movement capable of seizing power in all or part of the country (the various political forces in post-1911 China). In Southeast Asia, in contrast, there were few such opportunities for local elites to become involved in governing their own people. In the Dutch East Indies there were effectively no such opportunities much above the village level. In British-controlled Malaya and Burma there were more low-level government jobs for the local population, but most such jobs involved following the orders of British officials who made all of the important decisions. When there were not enough British citizens to staff sensitive jobs or the jobs were too low level (ordinary workers on the railroads and the police for example), the colonial government often brought in people from elsewhere in the empire (Indians for the Malaysian railroads for example). The French role in Indo-China was not much different. Most government jobs involving any degree of discretionary authority were held by the French. In short, the only way an indigenous person could gain experience in politics and governance was through rebellion, and the rebellions were vigorously suppressed until it was no longer possible to do so. At that point the colonial power withdrew, and the newly independent country got a ruler who had led the rebellion (Sukarno, Ho Chi Minh). In Malaysia, the British withdrew in 1957 after suppressing a Communist rebellion, but before doing so they made sure that most senior political, military, and police jobs would be in the hands of Malays rather than Chinese or Indian Malaysians (the rebellion was almost entirely led by Chinese Malayans, many from the Hakka minority).

The starkest contrast between the governance experience of Northeast and Southeast Asia, however, is not within these two regions taken together but between the East Asian region as a whole and much of Sub-Saharan Africa. In Sub-Saharan Africa the colonial powers eliminated virtually all local governance institutions and replaced them with colonial constructs. To slightly oversimplify they then drew boundaries around “countries” that bore little if any relation to the ethnic, linguistic, or precolonial governance structures on the continent. In West Africa Islamic nomads were put together with Islamic settled farmers and Christian producers of cocoa for export, not to mention a variety of ethnic and linguistic groups.4 The result has been a long series of civil wars and other forms of ethnic conflict.5

There is nothing fully comparable to this African colonial heritage in Southeast Asia, although Indonesia comes closest. The Dutch East Indies encompassed a wide variety of ethnic groups and some differences in religion and language that had limited connection with each other prior to Dutch colonialism. There was in fact a rebellion of the outer islands against Java in 1958, but it had more to do with the division of Sumatran oil revenues and the Cold War than with ethnic differences. The lack of any long-term historical basis for many of the boundaries aside from the fact that they had been drawn by the colonial powers also played a role in Indonesia’s Konfrontasi with Malaysia, when the British colonial territories of northern Borneo were added to Malaysia. Indonesia’s military actions to take the western half of New Guinea from the Dutch in 1962 and its takeover of East Timor in 1975–1976 also resulted from conflicts over where the borders of the Indonesian state should be drawn. In effect, the lack of widely recognized borders gave President Sukarno before 1965 and the Indonesian army after 1965 a basis for using military action to redraw the country’s borders and create instability in the region, instability that most of all distracted Indonesia itself from efforts to develop its own economy.

For the most part, however, unlike the case of much although not all of Africa, the colonial powers of Southeast Asia had been there for a century or more, and large majorities of the population in each country shared a common cultural heritage6—and, with the exception of Indonesia and to a lesser degree Burma, a common linguistic heritage.7 Indonesia solved the linguistic problem early on after independence by accepting as the national language Bahasa Indonesia, a trading language spoken by relatively few Indonesians in contrast to Javanese, but one that all Indonesians could and did accept. The Philippine archipelago prior to the Spanish had a population that spoke a variety of Malay languages, and many people still do, but the national language is based on Tagalog, which is an amalgam of Spanish, Malay, and other languages including English and Chinese, and most Filipinos also learn English. Most Filipinos, with the notable exception of Moslems in the south, are Christian.

In summary, at this level of generality, the nations of Northeast Asia do not have major border issues or fundamental conflicts over ethnicity and language, and their borders are well established for the most part because of a millennium or more of a shared history, culture, and language. Among other things, this shared history and culture made it easier, once systematic economic development efforts began, for large parts of the populations of these countries to see development efforts as benefiting the country and people as a whole rather than one ethnic group or region over another.

The northern part of Southeast Asia (Thailand, Vietnam, and to a lesser degree Burma) is more like Northeast Asia in terms of culture and language, but its borders are partly the result of decisions made by European colonial powers. The Cold War division of Vietnam at the seventeenth parallel in 1954, however, had the effect of engulfing Vietnam and the rest of Indo-China in war and making sustained economic growth impossible.

The Malay archipelago, which in a sense stretches from Malaysia through Indonesia and up through the Philippines, has borders that were completely the product of European colonial decisions but for the most part were made centuries ago. The region has widely diverse languages but nevertheless at different stages, as already noted, has established common languages with which to communicate across ethnic groups and common heritages (Islam in Malaysia and Indonesia and Catholic Christianity in the Philippines) shared by a majority of the population. Still, territorial issues disrupted development efforts in the early stages of Indonesian development and continue at a low level to plague development in the southern Philippines. Large ethnic minorities within Malaysia, as we shall see, have also had a major influence on the country’s development strategy, often in a negative way, and are an ongoing disruptive problem in Myanmar that, among other things, has provided an excuse for continued military dominance of the society to the detriment of development.8

Governance and Development in East Asian History

Having experience with self-government (Northeast Asia plus Thailand), accepted borders, and a common language and culture (most but not all of the rest of East Asia) simplifies the tasks facing leaders attempting governance of a country, but these conditions have been no guarantee that these countries would choose an appropriate path to sustained development either in historical times or more recently. Furthermore, the differences in cultures between and within Northeast and Southeast Asia have had an important influence in shaping how these countries and their governments have approached the challenges of development. This can be seen initially in how East Asian governments responded to the challenge of Western imperialism.

One of the important questions of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century East Asian history is why Japan and not China was the first to enter into a sustained period of modern economic growth beginning around 1900.9 In the early nineteenth century China was not only much larger but appeared to Western eyes a much more promising venue for commercial development. Japan had a tiny trade with the Dutch based in Nagasaki, but European and American trade at Canton was much larger. Commodore Matthew Perry of the U.S. Navy and his “black ships” did not appear off Japan’s Izu Peninsula until 1854, more than a decade after the British and China had fought the first Opium War (1839–1842), which established British control over Hong Kong and opened up a number of ports on the Chinese coast to international trade.

But it was the Japanese who almost from the start fully recognized the magnitude of the Western imperialist challenge and took action to deal with it. Unlike China, they did not fight Commodore Perry or the other Western powers. Understanding that Western naval might was superior to theirs, they instead negotiated diplomatic recognition and an opening up of trade with the West. More important, they overthrew their Tokugawa rulers and not just the rulers—they overthrew the entire feudal system of daimyo and samurai (lords and upper-class warriors) that presided over the feudal domains (han). This was a revolution from above in that leadership of the Meiji period remained in the hands of the existing upper classes even though they, the daimyo and samurai, lost their feudal stipends and their role of running and defending their local domains. The Japanese then set out to adopt those Western ways that seemed to be central to the West’s military power and economic prosperity. The army was among the first institutions to be reorganized and by 1895 was able to easily defeat China. In 1905 it defeated the Russian fleet and consolid...