![]()

The Chinese Sexagenary Cycle and the Ritual Foundations of the Calendar

Adam Smith

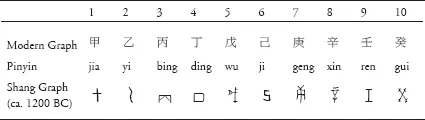

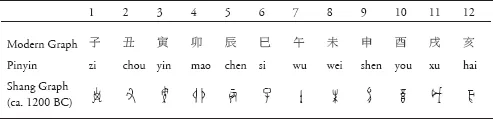

From the earliest appearance of literacy in East Asia, around 1250 BC, there is evidence of the routine use of a system for recording dates using cycles of named days. The more fundamental of these consists of ten terms and will be referred to here as the ‘10-cycle’ (table 1). By running the 10-cycle concurrently with a second cycle twelve days in length, the ‘12-cycle’ (table 2), a longer cycle of sixty days is generated, sixty being the lowest common multiple of ten and twelve. We will refer to this compound cycle as the ‘60-cycle’.1 At the time of their first attestation, the day was the only unit of time that the three cycles were used to record.2 Days within these cycles will be referred to in this chapter with the formulae n/60, n/10 and n/12. So, for example, 3/10 refers to the third day of the 10-cycle.

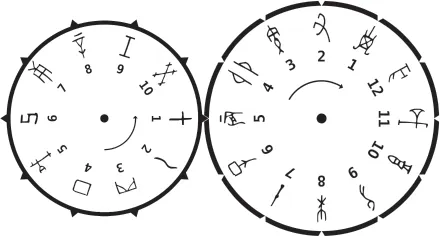

There are many ways of visualizing the compound 60-cycle.3 A comparativist might think of it as a pair of toothed wheels engaged with one another (figure 1), by analogy with the representations of the Mesoamerican Tzolk’in cycle, with which the Chinese 60-cycle has certain similarities. However, in the centuries after its first appearance it was conceived by its users in terms of a simple tabular format, with the sixty compound terms arranged in six vertical columns of ten terms each, one for each round of the 10-cycle. The first (rightmost) column began with the pair of terms for day 1/60 (1/10 paired with 1/12), below which followed 2/60 (2/10 and 2/12), 3/60 (3/10 and 3/12), and so on down to 10/60 (10/10 and 10/12) at the bottom. The beginning of a new column, as at 11/60 (1/10 and 11/12), coincided with the recommencement of the 10-cycle. The first repeat in the 12-cycle occurred on day 13/60 (3/10 and 1/12), at the third position in the second column. Many examples of this tabular format survive among the earliest remains of scribal training.4

The mathematical principles of the compound 60-cycle, and its timekeeping function, have obvious parallels in the calendars of other cultures. In addition to the 260-day Mesomerican Tzolk’in, a compound cycle of 13 × 20 days, there is a similarly direct parallel with the form and function of the 42-day round of the Akan calendar, a compound cycle of 6 × 7 days.5

The origins of the Chinese cycles are largely obscure.6 No compelling etymology for the names of the terms in the 10- and 12-cycles has ever been constructed, in Chinese, or any other language. They show no connection to the system of decimal numbers that also appears with the first evidence of the script. The 10-cycle is, fundamentally, the early Chinese week. The 12-cycle may have had a similar status among certain groups or in particular contexts but they have left no evidence of their existence. The well-known correlation of the 12-cycle with a list of animals is not attested within the first one thousand years of the cycle’s use.

The graphs used to write the terms of the 10-cycle may have been created for that purpose. That is, they are not obviously borrowings of graphs used to write other words. This is not the case for some terms in the 12-cycle. The writings for the sixth and tenth terms, for example, are phonologically motivated secondary uses of pictograms created to write ‘child’ (zi 子)7 and ‘beer’ (jiu 酒), employed as approximate phonetic spellers. This suggests that certain fundamental properties of the script were already established before they were applied to writing the 12-cycle.

In addition to their role in the calendar, terms in the 10-cycle, at the time of their first appearance and for several centuries after, were employed in names referring to dead kin. The 10-cycle and 60-cycle also underlay the calendrical apparatus that was used to schedule sacrificial performances directed towards these same dead kin, a central religious preoccupation of elites and probably the early Chinese population more broadly during the late second millennium.

The use of the 60-cycle to record dates was retained after the practice of naming dead kin with cyclical terms came to be abandoned, and the legacy of its role in scheduling ritual events continued to be felt, in elite funeral arrangements for example, into the mid first millennium BC. However, this break with the earlier ritual significance of the cyclical terms, as a means of referring to and commemorating dead family members, allowed them to be reinterpreted as a more abstract system of ordinals, one that could be creatively redeployed to label sequential or cyclical phenomena of many kinds in addition to days. Many of these new uses in their turn attracted a religious or magical focus.

FIGURE 1. The 60-cycle envisaged as a pair of toothed wheels representing the 10-cycle and the 12-cycle. Even-numbered positions never engage with odd-numbered positions. Six turns of the 10-cycle correspond to five turns of the 12-cycle, after which the system has returned to its original state. The arrangement shown corresponds to Day 41/60.

The Shang king list

The Shang (ca. 1600–1050 BC)8 king list, a sequence of more than thirty names over approximately twenty generations, is one of the earliest complex documents from East Asia that can be demonstrated to have been reliably preserved through textual transmission. A version of this list was available during the Western Han (206 BC – 25 AD), and is preserved in the Shi Ji (史記 Grand Scribe’s Records).9 This received version of the list is a very close match for the list that was reconstructed by twentieth-century scholarship from the sacrificial schedules reflected in divination records excavated at Anyang, location of the seat of the last seven generations of kings to appear in the list (table 3).10 Besides the bare sequence of royal names, the transmitted list was evidently equipped with further ancillary information. It marked instances of fraternal succession, for example, and may have provided cues to some of the anecdotes that pad out the version of it that appears in the Shi Ji.

A remarkable feature of the king list, that the list itself does nothing to explain, is the fact that every king is named af...