![]()

PART I

THE NATURE OF EMERGENCE

The only thing that makes life possible is permanent, intolerable uncertainty: not knowing what comes next.

—Ursula K. LeGuin, The Left Hand of Darkness

Emergence is nature’s way of changing. We see it all the time in its cousin, emergencies. What happens?

A disturbance interrupts ordinary life. In spite of natural responses, such as grief or fear or anger, people differentiate—take on different tasks. For example, in an earthquake, while many are immobilized, some care for the injured. Others look for food or water. A few care for the animals. Someone creates a “find your loved ones” site on the Internet. A handful blaze the trails and others follow. They see what’s needed and bring their unique gifts to the situation. A new order begins to arise.

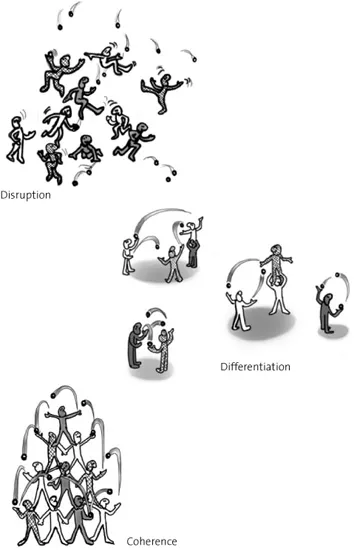

The pattern of change described in the introduction presented these aspects of emergent change:

Disruption breaks apart the status quo.

The system

differentiates, surfacing innovations and distinctions among its parts.

As different parts interact, a new, more complex

coherence arises.

People often speak of a magical quality to emergence, in part because we can’t predetermine specific outcomes. Emergence can’t be manufactured. It often arises from individual and collective intuition— instinctive and unconscious knowing or sensing without depending on the rational mind. It is often fueled by strong emotions—excitement, longing, anger, fear, grief. And it rarely follows a logical, orderly path. It feels much more like a leap of faith.

Emergence is always happening. If we don’t work with it, it will work us over. In human systems, it will likely show itself when strong emotions are ignored or suppressed for too long. Although emergence is natural, it isn’t always positive, and it has a dark side. Erupting volcanoes, crashing meteorites, and wars have brought emergent change. For example, new species or cultures fill the void left by those made extinct. Even wars can leave exciting offspring of novel, higher-order systems. The League of Nations and United Nations were unprecedented social innovations from their respective world wars.

Disrupt—Differentiate—Cohere1

Emergence seems disorderly because we can’t discern meaningful patterns, just unpredictable interactions that make no sense. But order is accessible when diverse people facing intractable challenges uncover and implement ideas that none could have predicted or accomplished on their own. Emergence can’t be forced—but it can be fostered.

The chapters in Part 1 speak to what emergence is, how it works, and some catches to be aware of when engaging it. Making sense of a situation is tough when you’re in the midst of the storm. Through understanding the nature of emergence, we can more effectively handle whatever changes and challenges come our way.

![]()

ONE

WHAT IS EMERGENCE?

If you wish to make an apple pie from scratch, you must first invent the universe.

—Carl Sagan, Cosmos

For most of us, the notion of emergence is tough to grasp because the concept is just entering our consciousness. When something new arises, we have no simple, shorthand language for it. The words we try seem like jargon. So we stumble with words, images, and analogies to communicate this whiff in the air that we can barely smell. We know it exists because something does not fit easily into what we already know.

Emergence disrupts, creates dissonance. We make sense of the disturbances that emergence creates partially through developing language that helps us to tease out useful distinctions. As the vocabulary to describe what is emerging becomes more familiar, our understanding increases. For example, disturbance, disruption, and dissonance are part of the language of engaging emergence. These terms are cousins, and I often use them interchangeably. Disruption is the most general of the three words. If something involves an emotional nuance, chances are that I call the disruption a disturbance. When conflict is involved or the disruption is particularly grating, with a lack of agreement or harmony, I will likely refer to its dissonance.

This chapter helps build a vocabulary we can all use by defining emergence. The chapter also provides a brief history of how our understanding of emergence has evolved. It offers some distinctions between strong and weak emergence and describes essential characteristics of emergence—what it looks like, how it behaves, and how it arises. The chapter ends by reflecting on the challenge of learning how to engage emergence.

Defining Emergence

In the preface, I defined emergence as simply as possible: order arising out of chaos. A more nuanced definition is higher-order complexity arising out of chaos in which novel, coherent structures coalesce through interactions among the diverse entities of a system. Emergence occurs when these interactions disrupt, causing the system to differentiate and ultimately coalesce into something novel.

Key elements of this definition are chaos and novelty. Chaos is random interactions among different entities in a given context. Think of people at a cocktail party. Chaos contains no clear patterns or rules of interaction. Make that a cocktail party in which no single culture prevails, so that no one is sure how close to stand to others, whether to make eye contact, or whether to use first or last names. Emergent order arises when a novel, more complex system forms. It often happens in an unexpected, almost magical leap. The cocktail party is actually a surprise party, and everyone knows where to hide and when to sing “Happy Birthday.”

Emergence produces novel systems—coherent interactions among entities following basic principles. In his bestseller Emergence, science writer Steven Johnson puts it this way: “Agents residing on one scale start producing behavior that lies one scale above them: ants create colonies; urbanites create neighborhoods; simple pattern-recognition software learns how to recommend new books.”1 Emergence in human systems has produced new technologies, towns, democracy, and some would say consciousness—the capacity for self-reflection.

A Short History of Emergence

If we want to engage emergence, understanding its origins helps. Scientist Peter Corning offers a brilliant essay on emergence.2 He brought a multitude of sources together to describe an evolution in perspectives. I have paraphrased some highlights:

Emergence has gone in and out of favor since 1875. According to philosopher David Blitz, the term was coined by the pioneer psychologist G. H. Lewes, who wrote, “[T]here is a cooperation of things of unlike kinds. The emergent is unlike its components … and it cannot be reduced to their sum or their difference.” By the 1920s, the ideas of emergence fell into disfavor under the onslaught of analysis. Analysis was seen as the best means to make sense of our world. In recent years, nonlinear mathematical tools have provided the means to model complex, dynamic interactions. This modeling capability has revived interest in emergence—how whole systems evolve.

Emergence is intimately tied to studies of evolution. Herbert Spencer, an English philosopher and contemporary of Darwin’s, described emergence as “an inherent, energy-driven trend in evolution toward new levels of organization.” It described the sudden changes in evolution—the move from ocean to land, from ape to human.

Although evolutionary scientists have done much of the work, people from a variety of disciplines have also struggled to explain this common and mysterious experience. What enables an unexpected leap of understanding in a field of study or practice? In 1962, Thomas Kuhn contributed to our understanding by coining the term paradigm shift to describe a tradition-shattering change in the guiding assumptions of a scientific discipline.3

Then the Santa Fe Institute, a leader in defining the frontiers of complex systems research, took the work further. Engagingly told by Mitchell Waldrop in his book Complexity, the story of how the Santa Fe Institute was born reads like a great adventure.4 In the mid-1980s, a hunch brought biologists, cosmologists, physicists, economists, and others to the Los Alamos National Laboratory to explore odd notions about complexity, adaptation, and upheavals at the edge of chaos.5 Though their disciplines used different terms, they shared a common experience with this strange form of change. They were no longer alone with their questions. Others were exploring the same edges.

They gave this experience a name: emergent complexity, or emergence for short. While emergence has aspects of the familiar—Mom’s nose, Dad’s eyes—it is its own notion. It isn’t just integrating old ideas with what’s new. It is something more—and different. It is whole systems evolving over time. Single-cell organisms interact, and multicellular creatures emerge. Humans become self-conscious and track their own evolution.

In Emergence, Steven Johnson speaks of how our understanding of emergence has evolved.6 In the initial phase, seekers grappled with ideas of self-organization without language to describe it. Without a coherent frame of reference, the ideas were like a magician’s illusion: our attention was diverted to the familiar while the real action was happening unseen in front of our noses.

As language emerged—complexity, self-organization, complex adaptive systems—a second phase began. These terms focused our attention in new directions. People started coming together across disciplines to understand the nature of these patterns. The Santa Fe Institute was central to this phase.

During the 1990s, we entered a third phase, applied emergence, in which we “stopped analyzing emergence and started creating it.”7 In other words, we could see emergence occurring naturally in phenomena like anthills. And we started working with it—for example, developing software that recognizes music or helps us find mates.

This book is about creating conditions for applied emergence in our social systems. It aims to help us work with the dynamics of emergent complexity so that our intentions are realized as life-serving outcomes.

Distinctions Between Weak and Strong Emergence

Scientists distinguish two forms of emergence: weak and strong emergence. Understanding this distinction clears up some confusion. Predictable patterns of emergent phenomena, such as traffic flows and anthills, are examples of weak emergence. In contrast, strong emergence is experienced as upheaval. When disruptions dramatically change a system’s form, as in revolutions and renaissances, strong emergence has occurred.

Weak emergence describes new properties arising in a system. A baby is wholly unique from its parents, yet is basically predictable in form. In weak emergence, rules or principles act as the authority, providing context for the system to function. In effect, they eliminate the need for someone in charge. Road systems are a simple example.

Strong emergence occurs when a novel form arises that was completely unpredictable. We could not have guessed its properties by understanding what came before. Nor can we trace its roots from its components or their interactions. We see stories on television. Yet we could not have predicted this form of storytelling from books.

As strong emergence occurs, the rules or assumptions that shape a system cease to be reliable. The system becomes chaotic. In our social systems, perhaps the situation is too complex for a traditional hierarchy to address it. Self-organizing responses to emergencies are an example. Such circumstances give emergence its reputation for unnerving leaps of faith.

Yet emergent systems increase order even in the absence of command and central control: useful things happen with no one in charge. Open systems extract information and order out of their environment. They bring coherence to increasingly complex forms. In emergent change processes, setting clear intentions, creating hospitable conditions, and inviting diverse people to connect does the work. Think of it as an extended cocktail party with a purpose.

Characteristics of Emergence

Although the conversation continues, scientists generally agree on these qualities of emergence:

RADICAL NOVELTY—At each level of complexity, entirely new properties appear (for example, from autocracy—rule by one person with unlimited power—to democracy, where people are the ultimate source of political power)

COHERENCE—A stable system of interactions (an elephant, a biosphere, an agreement)

WHOLENESS—Not just the sum of its parts, but also different and irreducible from its parts (humans are more than the composition of lots of cells)

DYNAMIC—Always in process, continuing to evolve (changes in transportation: walking, horse and buggy, autos, trains, buses, airplanes)

DOWNWARD CAUSATION—The system shaping the behavior of the parts (roads determine where we drive)

The phrase “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts” captures key aspects of these ideas. Birds flock, sand forms dunes, and individuals create societies. Each of these phrases names a related but distinct system. Each system is composed of, influenced by, but diffe...