![]()

1.

The Motivation Dilemma

Imagine you have the perfect person in mind to recruit and hire as a new employee. Your offer includes the highest salary ever offered to someone in this role. You are authorized to include whatever it takes to motivate this person to work in your organization—signing bonus, moving allowance, transportation, housing, performance bonuses, and a high-status office.

This was the situation facing Larry Lucchino in 2002. His mission: lure Billy Beane, the general manager of the small-market Oakland A’s, to the Boston Red Sox, one of the most storied and prestigious franchises in baseball. Lucchino was impressed with Billy’s innovative ideas about using sabermetrics—a new statistical analysis for recruiting and developing players.

The Red Sox offered Billy what was at the time the highest salary for a GM in baseball’s history. The team enticed him with private jets and other amazing incentives. As you may know from Moneyball: The Art of Winning an Unfair Game by Michael Lewis or from the hit movie starring Brad Pitt, Billy turned down the historic offer.

In real life, Billy is almost a shoe-in for the Baseball Hall of Fame because of the choices he has made, the relative success of the low-payroll Oakland A’s, and how he revolutionized the game of baseball through sabermetrics. He also provides an example of what you face as a leader. The Boston Red Sox could not motivate Billy Beane to be the team’s general manager with a huge paycheck and extravagant perks.

Billy’s mom, Maril Adrian, is one of my dearest friends. It was fascinating to hear her perspective as Billy’s life unfolded in the media over the decade. Sports Illustrated corroborated her assertion that money didn’t motivate Billy: “After high school, Beane signed with the New York Mets based solely on money, and later regretted it. That played into his decision this time.”1

To understand Billy’s choices is to appreciate the true nature of human motivation and why motivating people doesn’t work. Billy was motivated. He was just motivated differently than one might expect. He was not motivated by money, fame, or notoriety but by his love of and dedication to his family and the game of baseball. Trying to motivate Billy didn’t work because he was already motivated. People are always motivated. The question is not if a person is motivated but why.

The motivation dilemma is that leaders are being held accountable to do something they cannot do—motivate others.

I was sharing these ideas with a group of managers in China when a man yelled, “Shocking! This is shocking!” We all jumped. It was really out of the ordinary for someone in a typically quiet and reserved audience to yell something out. I asked him, “Why is this so shocking?” He replied, “My whole career, I have been told that my job as a manager is to motivate my people. I have been held accountable for motivating my people. Now you tell me I cannot do it.” “That’s right,” I told him. “So how does that make you feel?” “Shocked!” he repeated, before adding, “and relieved.”

This led to a robust conversation and an epiphany for leaders and human resource managers in the room. They came to understand that their dependence on carrots and sticks to motivate people had become common practice because we didn’t understand the true nature of human motivation. Now we do. Letting go of carrots and sticks was a challenge because managers did not have any alternatives. Now we do.

The Appraisal Process: How Motivation Happens

Understanding what works when it comes to motivation begins with a phenomenon every employee (and leader) experiences: the appraisal process.

Why do we say that people are already motivated?

Assuming that people lack motivation at any time is a mistake! For example, when you lead a team meeting, it’s a mistake to assume that participants are unmotivated if they are checking their text messages or tweeting instead of paying attention to you. They may just not be motivated to be at the meeting for the same reasons you are. They have appraised the situation, come to their own conclusions, and gone in their own motivational direction.

To experience this appraisal process for yourself, think about a recent meeting you attended. Reflect on your different thoughts and emotions as you noticed the meeting on your calendar, jumped off a call, and rushed to make the meeting on time. Did your feelings, opinions, or attitudes fluctuate from the time you added the meeting to your schedule to the time you left the meeting burdened with all the “next steps” on your to-do list?

This reflection process is what your people are doing all the time—either consciously or subconsciously. They are appraising their work experience and coming to conclusions that result in their intentions to act—either positively or negatively.

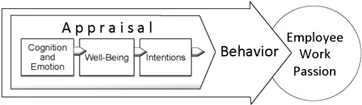

The appraisal process in figure 1.1 captures what you might have experienced in the example of attending the meeting.2 Whether mindful of it or not, you had thoughts and feelings about attending the meeting—you had both cognitive and emotional responses to the meeting. Is the meeting a safe or threatening event? Am I feeling supported or threatened? Is it a good use of or a waste of my time? Am I excited or fearful? Am I attending because I want to or because I feel I have to? Ultimately, how you feel about the meeting has the greatest influence on your sense of well-being. Your well-being determines your intentions, which ultimately lead to your behavior.

Figure 1.1 The appraisal process

Every day, your employees’ appraisal of their workplace leaves them with or without a positive sense of well-being. Their well-being determines their intentions, and intentions are the greatest predictors of behavior.3 A positive appraisal that results in a positive sense of well-being leads to positive intentions and behaviors that generate employee engagement.

The heart of employee engagement

The appraisal process is at the heart of employee engagement—and disengagement.4 I would be surprised if your organization doesn’t assess employee engagement or have some type of initiative aimed at improving it. Tons of data support the value of an engaged workforce. However, researchers have only recently explored how people come to be engaged.5 How do you improve engagement scores if you don’t understand the internal process individuals go through to become engaged?

You may find this encouraging: cutting-edge researchers discovered a higher level of engagement beyond the disengaged, actively disengaged, and engaged employee. They call it employee work passion. An individual with employee work passion demonstrates these five positive intentions:6

• Performs above standard expectations

• Uses discretionary effort on behalf of the organization

• Endorses the organization and its leadership to others outside the organization

• Uses altruistic citizenship behaviors toward all stakeholders

• Stays with the organization

In these studies, researchers identified twelve organizational and job factors that influence a person’s positive appraisal process.7 When the factors are in place, people are more likely to experience a positive sense of well-being that leads to positive intentions and behavior. Over time, they experience employee work passion.

You can build an organization that supports employee work passion. You can change job designs, workload balance, distributive and procedural justice issues, and other systems and processes proven to encourage people’s positive intentions. All of this is good news, but setting up new systems and processes takes time, and you need results now. What if you could help people manage their appraisal process today? You can.

This leads to a bold assertion: Motivating people may not work, but you can help facilitate people’s appraisal process so they are more likely to experience day-to-day optimal motivation.

Optimal motivation means having the positive energy, vitality, and sense of well-being required to sustain the pursuit and achievement of meaningful goals while thriving and flourishing.8

This leads to a second bold assertion: Motivation is a skill. People can learn to choose and create optimal motivational experiences anytime and anywhere.

Before you can help your people navigate their appraisal process or teach them the skill of motivation, you need to master it yourself—and that leads back to your meeting experience.

A Spectrum of Motivation

Asking if you or your staff were motivated to attend a meeting is the wrong question. Your answer is limited to a yes-no or a-little–a-lot response rather than the quality of motivation being experienced. Asking why people were motivated to attend the meeting, however, leads to a spectrum of motivation possibilities represented as six motivational outlooks in the Spectrum of Motivation model, figure 1.2.9

The Spectrum of Motivation model helps us make sense of the meeting experience. Consider which of the six motivational outlooks, shown as bubbles, best describes your experience before, during, and after your meeting. These outlooks are not a continuum. You can be at any outlook at any time and pop up in another one at any time. In the meeting example, you may have experienced one or all of these outlooks at one point or another:

Figure 1.2 Spectrum of Motivation model—Six motivational outlooks

• Disinterested motivational outlook—You simply could not find any value in the meeting; it felt like a waste of time, adding to your sense of feeling overwhelmed.

• External motivational outlook—The meeting provided an opportunity for you to exert your position or power; it enabled you to take advantage of a promise for more money or an enhanced status or image in the eyes of others.

• Imposed motivational outlook—You felt pressured because everyone else was attending and expected the same from you; you were avoiding feelings of guilt, shame, or fear from not participating.

• Aligned motivational outlook—You were able to link the meeting to a significant value, such as learning—what you might learn or what others might learn from you.

• Integrated motivational outlook—You were able to link the meeting to a life or work purpose, such as giving voice to an important issue in the meeting.

• Inherent motivational outlook—You simply enjoy meetings and thought it would be fun.

You may have noticed on the Spectrum of Motivation model that three of the outlooks are labeled as suboptimal—disinterested, external, and imposed. These outlooks are considered motivational junk food, reflecting low-quality motivation. Three of the outlooks are labeled as optimal—aligned, integrated, and inherent. These outlooks are considered motivational health food, reflecting high-quality motivation. To take full advantage of the Spectrum of Motivation, it is important to appreciate the different effects suboptimal and optimal motivational outlooks have on people’s well-being, short-term productivity, and long-term performance.

The Problem with Feeding People Motivational Junk Food

You buy dinner for your family at the local drive-through—burgers, fries, and shakes—with the intention of eating it at home together. The aroma of those fries is intoxicating. You simply cannot help yourself—you eat one. By the time you get home, the bag of French fries is empty.

Consider the effect junk food has on our physical and mental energy. How do we feel after downing the package of French fries? Guilty or remorseful? Even if we feel grateful and satisfied, what happens to our physical energy? It spikes dramatically and falls just as dramatically. How nourished are our bodies? A steady diet of junk food simply isn’t good for us. Even if we can justify an occasional splurge, we are wise to understand our alternative choices.

Parents, teachers, and managers promise more money, award prizes for contests, offer rewards, threaten punishment, apply pressure, and use guilt, shame, or emotional blackmail to encourage specific behaviors from children, students, and employees. When people give in to one of these tactics, they end up with a suboptimal motivational outlook—disinterested, external, or imposed. But, those rewards and punishments (carrots and sticks) are as hard to resist as those French fries—and just as risky.

Here’s a case in point. You receive an invitation from your health insurance provider to lose weight and win an iPad mini. You think, What do I have to lose except some weight? What do I have to gain except health and an iPad mini? Think again.

A recent study followed people who entered contests promising a prize for losing weight. They found that, indeed, many people lost weight and won their prize. However, these researchers did something that others had not done. They continued to follow the behaviors and results of the prizewinners. What they found reinforced vast motivational research findings regarding incentives. Within twelve weeks after winning their prize, people resumed old behaviors, regained the weight they had lost, and then added even more weight! Financial incentives do not sustain changes in personal health behaviors—in fact, they undermine those behaviors over time.10

Rewards may help people initiate new and healthy behaviors, but they fail miserably in helping people maintain their progress or sustain results. What may be more disturbing is that people are so discouraged, disillusioned, and debilitated by their failure, they are less likely to engage in further weight-loss attempts.

So why do over 70 percent of wellness programs in the United States use financial incentives to encourage healthy behavior changes?11

• If people participate, without perceived pressure, in a weight-loss program offering small financial incentives, there is some likelihood they will lose weight initially. However, studies reporting these weight-loss successes were conducted only during the period of the contest. They didn’t track maintenance. “The rest of the story” is one ...