![]()

CHAPTER 1

Welcome to Predator

“Welcome to the Predator.”

Chuck, a longtime instructor at the 11th Reconnaissance Squadron, stood in front of a Predator, giving us the welcome speech. It was my first day of Predator training at Creech Air Force Base in Nevada.

My class of twenty-nine new pilots and sensor operators crowded near the front of the aircraft as Chuck spoke. Up front, the newly enlisted sensor operators watched Chuck’s every move as he pointed out the targeting pod, which hung below the chin of the Predator, and the different antennas used to control the aircraft.

I was standing near the back with the other pilots. At the time I entered the program in December 2003, there were few, if any, volunteers. Most Predator pilots had been forced out of other programs because they had damaged the Air Force’s manned aircraft or failed to meet the technical or professional standards laid out for each aircraft. Some were there due to injuries that kept them out of manned cockpits.

Few were there because they wanted to be. I was one of only four volunteers.

Ever since I was a kid, I dreamt about being a combat pilot. Growing up in Mississippi, I was the second of two children. Independent by nature, I was fascinated with how machines were constructed. I had an Erector set that I used to design my own spacecraft. I imagined traveling to unexplored worlds, fighting in great space battles, or just discovering some lost civilization.

But it wasn’t until my father took me to an air show at Hawkins Field, in Jackson, Mississippi, when I was five that I discovered my true passion. The Confederate Air Force, now known as the Commemorative Air Force, was reenacting a World War II air battle.

The ground vibrated with the rumble of the piston engines as German Messerschmitt and American Mustang fighters danced in a mad circle in the sky. Pyrotechnics erupted around the airfield, simulating bomb strikes and antiaircraft fire. The noise was tremendous, exhilarating, and wonderful.

But nothing compared to when my father bought me a ticket to climb aboard the B-29 bomber Fifi.

I scrambled up the crew ladder, with my dad’s careful hand guiding me, and clambered into the copilot’s seat. A massive dashboard spread out in front of me with an impossible number of dials and gauges. I cranked on the yoke and imagined what it would have been like to fly the plane.

I was hooked.

I worked hard in high school to earn a spot at the US Air Force Academy because of its guaranteed pilot training program. But after I graduated in the class of 1992, my flight training was delayed because of the post–Cold War drawdown. Instead, I went to intelligence training at Goodfellow Air Force Base in San Angelo, Texas, where I became an intelligence officer.

Three years after I was commissioned, a “no-notice” slot in pilot training at Columbus Air Force Base in Mississippi opened. A fellow USAFA classmate had dropped out of training a week before it started due to family reasons, leaving an open billet the Air Force had to fill. The Air Force Personnel Center pulled my name off a list of alternates and served me “no-notice” to pick up everything and move to Mississippi. I accepted the spot without any reservations. Over the next eight years, I flew trainers and the E-3 Airborne Warning and Control System, which had a massive radar dish on its back. The plane provided command and control to fighters. I flew counterdrug operations off the coast of South America, I patrolled the skies off North Korea as the country’s surface-to-air missiles tracked my every move, and I flew presidential escort in East Asia.

I was a good pilot, but my Air Force career had been derailed by my stint as an intelligence officer. My chances of becoming a fighter pilot were slim to none. After a few years as an instructor, it was time to return to the AWACS. I balked. I wanted to stay in the Air Force, but I didn’t want to fly the AWACS again. I knew there was no chance it would deploy and I wanted to do my part. The planes had been sent home from the war and were not expected to return. They had become another noncombat assignment.

It was 2003 and the war in Afghanistan was already two years old. The war in Iraq was just beginning. When a slot opened in the Predator training pipeline, I asked for it. After some wrangling, I got it. It wasn’t a fighter, but I wanted it because the Predator gave me a chance to stay in the cockpit and contribute to the war effort.

But looking at the Predator in the hangar, I still had my reservations.

I was thirty-three years old, and as Chuck spoke I pondered the prudence of my decision. Like every pilot in the Air Force, I still felt aviation was accomplished in an aircraft, not at a computer terminal on the ground. Trained professionals sitting in the cockpit flew airplanes. Pilots didn’t fly from a box. No pilot has ever picked up a girl in a bar by bragging that he flew a remote-controlled plane.

One of my favorite T-shirts had a definition for “pilot” printed across the chest. It sort of summed up the pilot mind-set, albeit in a humorous way.

Pi-lot: n. The highest form of life on earth

To me, the shirt didn’t portray arrogance as much as confidence. Flying was special. Few people got to experience the world from thirty thousand feet with a flying machine strapped to their backs and under their own control. From the cockpit, we could see the curve of the earth and watch the cars on the highway reduced to the size of ants. Every time I climbed into the sky, I felt the same exhilaration. Aviation wasn’t a job. It was my passion. It was my calling. It was something I had to do to feel complete.

Most men identify themselves through their work, and I had the best job on the planet.

But flying high above the earth has its dangers too. That is when the confidence, often mistaken for arrogance, comes to the surface.

We trusted our skills, because when you’re that high above the ground, no one can come up and save you. Unlike cars, aircraft weren’t vehicles you could just pull over when they broke down. But that factor was taken out of the equation in the Predator. Unless the aircraft landed on top of the cockpit on the ground, its pilots were safe no matter what happened. I looked down on the Predator because of that fact. Flying it took away all the exhilaration of being airborne and all the adventure of being a pilot.

The first training lesson was Chuck’s welcome speech. He delivered it with the cadence of a speaker who had given the same speech one time too many. He wasn’t bored, but his tone lacked enthusiasm. His words came out flat and practiced. His insights into the aircraft came from experience, not theory.

Chuck had commanded the 11th when it deployed to Afghanistan to support the invasion. He’d seen the Predator in combat and knew what it could do. As he walked around the aircraft, he carried himself with the military bearing of an officer, even if he was dressed in only khaki pants and a golf shirt.

“This is a system unlike any you’ve seen,” he said.

I had to agree.

It also looked like no airplane I’d ever seen. The pictures didn’t do it justice. Until the Predator came along in 1994, typical unmanned aerial vehicles were not much larger than a remote-controlled hobby airplane. In my mind’s eye, I figured the Predator would be about the same size.

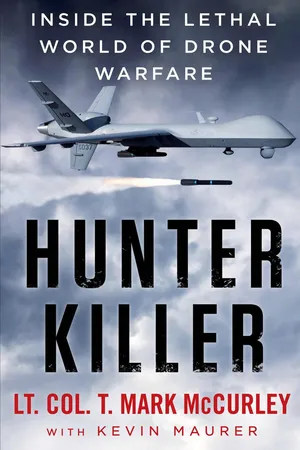

Built by General Atomics, the MQ-1 Predator was about the size and weight of a Cessna 172 and looked like an angry gray bird with its inverted V-shaped tail resting lightly on the ground. It crouched as if yearning to launch into the sky.

Chuck invited us to come closer. The group of students crowded in. Up close, it was easy to see how the aircraft lacked durability. The thin composite body felt like dry paper. Its anemic landing gear was just springs that flexed with the weight of the aircraft. A converted 115-horsepower four-cylinder snowmobile engine, retrofitted with a turbocharger, powered the slender white prop at the back. The aircraft could reach altitudes of up to twenty-five thousand feet and fly for more than twenty hours without refueling. The Predator was impressive in its simplicity.

Chuck finished with the specs on the aircraft and moved on to the history. The Predator was created in response to the US Air Force’s call for an unmanned surveillance plane in 1993. General Atomics, based out of San Diego, originally presented its idea to the Air Force.

Neal and Linden Blue, oil magnates who own a lot of property in Telluride, acquired General Atomics in 1986 for nearly fifty million dollars. While living in Nicaragua, Neal had watched the country’s ruling family, the Somozas, be deposed by the Soviet-backed Sandinista coalition. Unable to fight, he wondered what it would take to fly an unmanned airplane using GPS into the huge petroleum, oil, and lubricants (POL) tanks fueling the Soviet-backed army. He wanted to cripple the new regime. The acquisition of General Atomics offered the means for Neal to achieve part of his wish.

In 1992, he hired retired admiral Thomas J. Cassidy to organize General Atomics Aeronautical Systems Inc. Cassidy’s mission was to research and produce unmanned aircraft. The company’s first attempt was the Gnat. It was built with off-the-shelf parts and sported a camera turret similar to those found on traffic helicopters. It could stay aloft for nearly forty hours, but it was too small to carry weapons and its range was limited because the controller had to keep the Gnat in sight to control it.

Then came the Predator.

Using what their researchers had learned from the Gnat, the company designed the aircraft with an inverted tail and a massive video sensor ball under the nose. The Predator first flew in 1994 and was introduced to the Air Force shortly after. The pilots running the Air Force met it with skepticism, but Air Force intelligence saw its value.

The Predator could fly over targets and send back high-resolution imagery even on bad weather days. As an added bonus, the aircraft were cheap, at 3.2 million dollars per plane. Four airframes with a ground control station cost about forty million dollars to buy and operate. By comparison, each new F-22 Raptor cost more than two hundred million dollars to purchase.

The first Predator flight was in July 1994. By the time the war in Afghanistan started, the Air Force had sixty Predators, some of which had flown over Bosnia. In February 2001, the Predator fired its first Hellfire missiles and its role as a reconnaissance aircraft started to change. A year later, Predators destroyed Taliban leader Mullah Omar’s truck. They also killed an Afghan scrap-metal dealer who looked like Osama bin Laden. In March 2002, a Predator fired a Hellfire missile in support of Rangers fighting on Roberts Ridge during Operation Anaconda. It was the first time a Predator provided close air support to troops on the ground.

The aircraft was valuable on paper, but it wasn’t yet considered a key cog in combat operations or even aviation for that matter. The Air Force knew it needed it to fly intelligence missions, but the potential importance of the program hadn’t reached the leadership. Flying a Predator was the last stop on most career paths, evident by the austere conditions of the training base. Guys didn’t move on to other units to brag about their Predator experience. They left the service as soon as they could. I didn’t know it at the time, but when I volunteered in 2003, that was all about to change.

Creech Air Force Base sat across US Route 95 from the little desert town of Indian Springs. Area 51 and the nuclear test range sat along the northern edge of the base. Indian Springs was the antithesis of Las Vegas in every way. The sleepy town consisted of mostly trailers, two gas stations, and a small casino that earned more in the restaurant than on the gaming floor. I drove by the local school and noticed an old Navy fighter parked out front. It was painted to resemble the Thunderbirds, the Air Force’s demonstration team. Its shattered canopy played host to nesting birds.

The base wasn’t much better. US Route 95 ran parallel to the old single runway, limiting the base’s ability to expand. To the northwest was Frenchman Lake, where the military tested nuclear weapons in the 1950s. When I drove through the gate the first time, I entered a time warp. A few World War II–era barracks buildings existed at the base. They were made of wood, whitewashed in an effort to make them look new. As I passed them, I saw they had been converted into a chow hall, theater, and medical facility. The only new building was on the east end of the base, where the 11th made its home. For the next four months, I’d spend my days learning to fly the Predator in that building.

By 2003, the Air Force was acquiring two new aircraft a month. It now had to find pilots to fly the expanding fleet of Predators. There were nine other pilots in my class. We stayed in the back of the group as Chuck talked, somewhat aloof. It was an unconscious defense against something we didn’t understand: RPA flight. Everything about the Predator was foreign. We were still trying to determine if the aircraft passed the smell test.

Never before had a Predator formal training unit class had so many pilot volunteers. The guys with me saw the little Predator differently. To them, it wasn’t a dead-end assignment; it was an opportunity.

Another pilot, Mike, stood next to me. I recognized Mike from our school days at the Air Force Academy, but I had never really known him personally. Our careers hadn’t crossed paths since graduation. He’d flown KC-135 aerial refueling tankers and F-16 fighters, while I flew trainers and the AWACS.

Mike was a couple of inches taller than me. He had a runner’s build, and unlike my graying hair, his remained as black as when he’d entered the service. His eyes burned with an intensity I’ve seen in few officers. We caught up briefly before Chuck started.

“You volunteer?” Mike asked.

Volunteering was an important thing to us. One of the guys in the class had been assigned to Creech after being sent home early from a deployment. He’d knocked up an airman. The four of us who volunteered wanted it known that we chose this life. It was not foisted upon us.

“Yeah, I wanted to avoid a third straight noncombat assignment,” I said. “You?”

Mike shook his head.

“I saw the writing on the wall,” he said. “Late rated and late to fighters meant it was unlikely I could see a command.” His career in aviation had been delayed, much like mine had been.

“Tough,” I said.

“It is what it is,” he said.

I nodded understanding.

From the back of the class, I looked at the young faces of the nineteen sensor operators who would train with us. These fresh-faced eighteen-year-olds would make up the second half of the crew. The pilot controlled the aircraft and fired the weapons. The sensor operator ran the targeting systems, cameras, and laser designators. Together, we had to form a tight, efficient crew.

As we walked back to the classroom, I took stock of the class. Raw recruits, washouts from other career fields, problem children, and passed-over fighter pilots yearning to prove they deserved a shot were building the Predator community. We all had chips on our shoulders. We all wanted to prove we belonged in the skies over the battlefield. It was the pilots who never forgot who would excel.

![]()

CHAPTER 2

Learning to Fly

All the pilots knew how to fly, but we learned quickly that that didn’t matter in the Predator. It was a couple of weeks into the program and I was just settling into the “box,” or cockpit, for my first flight.

The box was a modified Sea-Land container technically called a ground control station (GCS). The tan container had a vault-like door at one end that opened into a narrow walkway that led to the “cockpit” at the other end. The floor and walls were covered in rough gray carpet and the lights were dim to eliminate glare on the monitors.

Along one side of the walkway was a series of computer racks and two support stations. At the end of the container were two tan chairs in front of the main control station. A small table jutted out between the pilot station on the left and the sensor operator station on the right. A standard computer keyboard sat on the table in front of each station, bracketed by a throttle and control stick. Below the table was a set of rudder pedals. Both the pilot and sensor operator stations had a throttle on the left and a stick on the right, but only the pilot’s controls flew the aircraft. The sensor operator’s “throttle” and “stick” controlled the targeting pod.

I shivered as I looked over my shoulder at Glenn, my instructor.

“It’s cold in here,” I said. “Is it always like this?”

“Mostly,” he said. “You’ll get used to it.”

The HVAC system pumped freezing air into the numerous electronics racks to keep them from overheating. Temperatures...