- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

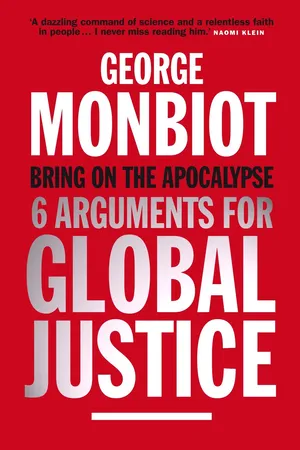

In these incendiary essays, George Monbiot tears apart the fictions of religious conservatives, the claims of those who deny global warming and the lies of the governments and newspapers that led us into war. He takes no prisoners, exposing government corruption in devastating detail while clashing with people as diverse as Bob Geldof, Ann Widdecombe and David Bellamy.

But alongside his investigative journalism, Monbiot's book contains some remarkable essays about what it means to be human. Monbiot explores the politics behind Constable's The Cornfield, shows how driving cars has changed the way we think and argues that eternal death is a happier prospect than eternal life.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Contents

Introduction:

Four Missed Meals Away from Anarchy

Arguments With God

Bring on the Apocalypse

The Virgin Soldiers

Is the Pope Gay?

A Life With No Purpose

America the Religion

Arguments With Nature

Junk Science

Mocking Our Dreams

Preparing for Take-Off

A Lethal Solution

Giving Up On Two Degrees

Crying Sheep

Feeding Frenzy

Natural Aesthetes

Bring Them Back

Seeds of Distraction

Arguments With War

Thwart Mode

One Rule for Us

Dreamers and Idiots

The Moral Myth

The Lies of the Press

War Without Rules

A War of Terror

Back to Front Coup

Peace Is for Wimps

Asserting Our Right to Kill and Maim Civilians

A War Dividend

The Darkest Corner of the Mind

Arguments With Power

I’m With Wolfowitz

Still the Rich World’s Viceroy

On the Edge of Lunacy

This Is What We Paid for

Painted Haloes

The Corporate Continent

The Flight to India

How Britain Denies Its Holocausts

A Bully in Ermine

Lady Tonge: An Apology

Arguments With Money

Property Paranoia

Britain’s Most Selfish People

Theft Is Property

Expose the Tax Cheats

Bleeding Us Dry

An Easter Egg Hunt

A Vehicle for Equality

Too Soft On Crime

Media Fairyland

The Net Censors

Arguments With Culture

The Antisocial Bastards in Our Midst

Driven Out of Eden

Breeding Reptiles in the Mind

Willy Loman Syndrome

The New Chauvinism

Notes

Introduction

Four Missed Meals Away from Anarchy

I am writing this on a train rattling slowly down the Dyfi valley. It is April and the oaks are twitching into life. A moment ago I saw a lamb that had just been born. Afterbirth still trailed from the ewe like scarlet bunting. The Dyfi is lower than it should be at this time of year; its pale shoulders have been exposed. On its banks is the debris of the winter storms: sticks and leaves trapped in the branches of the sallows; trees like the picked skeletons of whales dumped in the grass. It is hard to believe that the river could have mustered such force.

It has not taken me long to adjust to my new home. When I travel to London, I can think only of the rivers and the hills. It is strangely peaceful here, almost as if the cruelty of nature has been suspended. But so, in its way, is every landscape I have travelled through. The houses lining the railway canyon north of Euston look like prisons, but no one riots. In the West Midlands the demolition of our industry takes place without ceremony or panic. Machines stack and sift the rubble; property developers park their Audis and stroll around the remains. There are no mobs; no fires; only the occasional bomb. The country is slumbering through a deep and unremarked peace.

By peace, I mean not just an absence of war. I also mean an absence of the competition for resources encountered in any place or at any time in which the necessities of life are short. Whenever I read about the fighting in Iraq or the massacres in Congo and Darfur, or the torture and repression in Burma or Uzbekistan, or the sheer bloody misery of life in Malawi or Zambia, I am reminded that our peace is a historical and geographical anomaly.

It results primarily from a surplus of energy. A lasting surplus of useful energy is almost unknown to ecologists. Trees will crowd out the sky until no sunlight reaches the forest floor. Bacteria will multiply until they have consumed their substrate. A flush of prey will be followed by a flush of predators, which will proliferate until the prey is depleted. But we have so far been able to keep growing without constraint. By extracting fossil fuels, we can mine the ecological time of other eras. We use the energy sequestered in the hush of sedimentation – the infinitesimal rain of plankton on to the ocean floor, the spongy settlement of fallen trees in anoxic swamps – compressed by the weight of succeeding deposits into concentrated time. Every year we use millions of years accreted in other ages. The gift of geological time is what has ensured, in the rich nations, that we have not yet reached the point at which we must engage in the struggle for resources. We have been able to expand into the past. Fossil fuels have so far exempted us from the violence that scarcity demands.

There are a few exceptions. Some of the troops sent abroad to secure and control other people’s energy supplies will die. Otherwise we have outsourced the killing. Other people kill each other on our behalf; we simply pay the victors for the spoils. Oil wars have been waged abroad ever since petroleum became a common transport fuel. Columbite-tantalite, a mineral of whose very existence we are ignorant but upon which much of our post-industrial growth depends, has been one of the main causes of a conflict that has led to some 4 million deaths in the Democratic Republic of Congo. We pay not to fight.

One phrase, picked up in the rhythm of the train, keeps chugging through my head. “Every society is four missed meals away from anarchy.” I heard it at a meeting a fortnight ago.1 Our peace is as transient and contingent as the water level in the Dyfi river.

Some of the accounts of the violence in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina were exaggerated, but not all of them. The slightest disruption in the supply of essential goods, coupled with the state’s failure to assert its monopoly of violence, is sufficient to persuade people to rob, threaten, even to kill. A violent response to scarcity affects even those who are in no danger of starvation. Look at what happens on the first day of the Harrods sale. Prosperous people, aware that bargains are in short supply, shove, elbow, scramble, sometimes exchange blows, in their effort to obtain one of a small number of dinner services or carriage clocks or other such symbols of refinement. Civilisation, so painfully maintained by their hypocritical British manners at other times, disintegrates like the china they tussle over at the first hint of competition. We take our peace for granted only because we fail to understand what sustains it.

Order, in such circumstances, can be quickly restored through the superior force of arms. But order in times of scarcity is not the same as order in times of plenty. It is harsher and less flexible; the realities of power are more keenly felt. There have been instances where the superior force intervenes to try to ensure a fair distribution of resources. This happened, for example, in Britain during the Second World War. More commonly, it intervenes to protect those who still possess supplies from those who do not. It is not always the state that performs this role: the rich also arrange their own security, paying other people to fight.

Look at the compounds and condominiums in Johannesburg, Nairobi, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Mumbai and Jakarta. The rich live behind razor wire, broken glass, dogs and armed guards. It is, to my eyes, a hideous existence. But only one thing is worse than living in a gated community in these cities: not living in a gated community. Without guards, you sleep with one ear tuned to the breaking of your door.

Yet even here there is, most of the time, no absolute shortage of any essential resource. In all these places you can buy whatever you want. There is no shortage of food or fuel or clean water or any other commodity, if you have money. Money is the limiting factor the absence of which keeps people hungry. But the situations I would like you to consider are those in which not money but the resources themselves become the constraint.

There are three major commodities whose supply, in many countries, could become subject to absolute constraints during our lifetimes: liquid fuels, fresh water, and food. Over the past three years there has, at last, been some public discussion about “peak oil”, the point at which global petroleum supplies peak and then go into decline. I have come to believe that some predictions of its imminent arrival have been exaggerated, but it is clear that it will happen sooner or later, and probably within the next 30 years. In a sense, the date of peaking is irrelevant. Once infrastructure that depends on the consumption of petroleum has been established, demand for this commodity is inelastic: if you live in a distant suburb, you cannot get to work or to the shops or to school without it. This means that absolute scarcity can occur ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Bring on the Apocalypse by George Monbiot in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Historia y teoría política. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.