- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

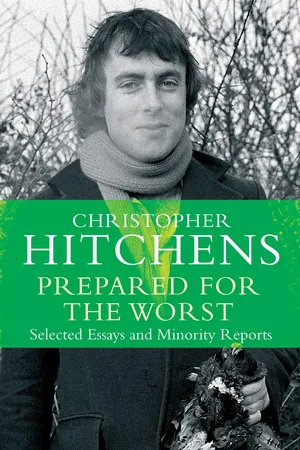

Christopher Hitchens is widely recognized as having been one of the liveliest and most influential of contemporary political analysts. Prepared for the Worst is a collection of the best of his essays of the 1980s published on both sides of the Atlantic. These essays confirmed his reputation as a bold commentator combining intellectual tenacity with mordant wit, whether he was writing about the intrigues of Reagan's Washington, a popular novel, the work of Tom Paine, the man George Orwell, or reporting (with sympathy as well as toughness) from Beirut or Bombay, Warsaw or Managua.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CONTENTS

Introduction

Good and Bad

Blunt Instruments

Datelines

In the Era of Good Feelings

Prepared for the Worst

INTRODUCTION

NADINE GORDIMER once wrote, or said, that she tried to write posthumously. She did not mean that she wanted to speak from beyond the grave (a common enough authorial fantasy), but that she aimed to communicate as if she were already dead. Never mind that that ambition is axiomatically impossible of achievement, and never mind that it sounds at once rather modest and rather egotistic, to say nothing of rather gaunt. When I read it I still thought: Gosh. To write as if editors, publishers, colleagues, peers, friends, relatives, factions, reviewers, and consumers need not be consulted; to write as if supply and demand, time and place, were nugatory. What a just attainment that would be, and what a pristine observance of the much-corrupted pact between writer and reader.

The essays, articles, reviews, and columns that comprise Prepared for the Worst do not meet, or approach, the exacting Gordimer standard in any respect. In fact, so far from addressing people posthumously, I feel rather that I’m standing over my collection like an anxious parent. Friends and even acquaintances tend naturally to praise my little son, at least to my face, and I’ve become used to inserting the descant of allowances for myself: you’ve got to realize that he’s a bit spoiled; he’s keener to talk than he is on what he’s saying; he’s a bit lacking in concentration; and so on. Still, the teacher did say just the other day that he was very inquiring and showed distinct promise. Sympathetic, encouraging nods all around.

You don’t get that kind of indulgence for your prose. Hopeless, then, to seek to justify the ensuing. Yes, the piece on Reagan’s mendacity was written to the tune of an emollient week in the national press; yes, the review of Brideshead was composed in response to a TV travesty then in vogue; yes, the report from Beirut understates the horror (didn’t everybody?). But then, might it not be said that the Polish article has a dash of prescience? The Paul Scott essay perhaps a hint of perspective? Forget it. Never explain; never apologize. You can either write posthumously or you can’t.

Fortunately, Ms. Gordimer does set another example that a mortal may try to follow. She combines an irreducible radicalism with a certain streak of humor, skepticism, and detachment. She is also a determined internationalist. My choice among her novels would be A Guest of Honor, wherein the central character sees his beloved revolution besmirched and yet does not feel tempted—entitled might be a better word—to ditch his principles. The whole is narrated with an exceptional clarity of eye, ear, and brain, and there is no sparing of “progressive” illusions. The result is oddly confirming; you end by feeling that the attachment to principle was right the first time and cannot be, as it were, retrospectively abolished by the calamitous cynicism that only idealists have the power to unleash.

Most of the articles and essays in this book were written in a period of calamitous cynicism that was actually inaugurated by calamitous cynics. It was—I’m using the past tense in a hopeful, nonposthumous manner—a time of political and cultural conservatism. There was a ghastly relief and relish in the way in which inhibition—against allegedly confining and liberal prejudices—was cast off. In the United States, this saturnalia took the form of an abysmal chauvinism, financed by MasterCard and celebrating a debased kind of hedonism. In Britain, where there were a few obeisances to the idea of sacrifice and the postponement of gratification, it took the more traditional form of restoring vital “incentives” to those who had for so long lived precariously off the fat of the land. In both instances, the resulting vulgarity and spleen were sufficiently gross to attract worried comment from the keepers of consensus.

Now, I have always wanted to agree with Lady Bracknell that there is no earthly use for the upper and lower classes unless they set each other a good example. But I shouldn’t pretend that the consensus itself was any of my concern. It was absurd and slightly despicable, in the first decade of Thatcher and Reagan, to hear former and actual radicals intone piously against “the politics of confrontation.” I suppose that, if this collection has a point, it is the desire of one individual to see the idea of confrontation kept alive.

Periclean Greeks employed the term idiotis, without any connotation of stupidity or subnormality, to mean simply “a person indifferent to public affairs.” Obviously, there is something wanting in the apolitical personality. But we have also come to suspect the idiocy of politicization—of the professional pol and power broker. The two idiocies make a perfect match, with the apathy of the first permitting the depredations of the second. I have tried to write about politics in an allusive manner that draws upon other interests and to approach literature and criticism without ignoring the political dimension. Even if I have failed in this synthesis, I have found the attempt worth making.

Call no man lucky until he is dead, but there have been moments of rare satisfaction in the often random and fragmented life of the radical freelance scribbler. I have lived to see Ronald Reagan called “a useful idiot for Kremlin propaganda” by his former idolators; to see the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union regarded with fear and suspicion by the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (which blacked out an interview with Miloš Forman broadcast live on Moscow TV); to see Mao Zedong relegated like a despot of antiquity. I have also had the extraordinary pleasure of revisiting countries—Greece, Spain, Zimbabwe, and others—that were dictatorships or colonies when first I saw them. Other mini-Reichs have melted like dew, often bringing exiled and imprisoned friends blinking modestly and honorably into the glare. Eppur si muove—it still moves, all right.

Religions and states and classes and tribes and nations do not have to work or argue for their adherents and subjects. They more or less inherit them. Against this unearned patrimony there have always been speakers and writers who embody Einstein’s injunction to “remember your humanity and forget the rest.” It would be immodest to claim membership in this fraternity/sorority, but I hope not to have done anything to outrage it. Despite the idiotic sneer that such principles are “fashionable,” it is always the ideas of secularism, libertarianism, internationalism, and solidarity that stand in need of reaffirmation.

GOOD AND BAD

THOMAS PAINE

The Actuarial Radical

“GOD SAVE great Thomas Paine,” wrote the seditious rhymester Joseph Mather at the time:

His “Rights of Man” explain To every soul

He makes the blind to see

What dupes and slaves they be

And points out liberty From pole to pole.

He makes the blind to see

What dupes and slaves they be

And points out liberty From pole to pole.

As befits an anthem to the greatest Englishman and the finest American, this may be rendered to the tune of “God Save the King” or “My Country Tis of Thee.” The effect is intentionally blasphemous and unintentionally amiss. Napoleon Bonaparte, when he called upon Paine in the fall of 1797, proposed that “a statue of gold should be erected to you in every city in the universe.” He fell just as wide of the mark in his praise as Mather had in his parody. Thomas Paine was never a likely subject for a cult of personality. He still has no real memorial in either the country of his birth or the land of his adoption. I used to think this was unfair, but it now seems to me at least apposite.

How right Paine was to call his most famous pamphlet Common Sense. Everything he wrote was plain, obvious, and within the mental compass of the average. In that lay his genius. And, harnessed to his courage (which was exceptional) and his pen (which was at any rate out of the common), this faculty of the ordinary made him outstanding. As with Locke and the “Glorious Revolution” of 1688, Paine advocated a revolution which had, in many important senses, already taken place. All the ripening and incubation had occurred; the enemy was in plain view. But there are always some things that sophisticated people just won’t see. Paine—for once the old analogy has force—did know an unclad monarch when he saw one. He taught Washington and Franklin to dare think of separation.

The symbolic end of that separation was the handover of America by General Cornwallis at Yorktown. As he passed the keys of a continent to the stout burghers, a band played “The World Turned Upside Down.” This old air originated in the Cromwellian revolution. It reminds us that there are times when it is conservative to be a revolutionary, when the world must be turned on its head in order to be stood on its feet. The late eighteenth century was such a time.

“The time hath found us,” Paine urged the colonists. It was a time to contrast kingship to sound government, religion to godliness, and tradition to—common sense. Merely by stating the obvious and sticking to it, Paine had a vast influence on the affairs of America, France, and England. Many critics and reviewers have understated the thoroughness of Paine’s commitment, representing him instead as a kind of Che Guevara of the bourgeois revolution. Madame Roland found him “more fit, as it were, to scatter the kindling sparks than to lay the foundation or prepare the formation of a government. Paine is better at lighting the way for revolution than drafting a constitution … or the day-to-day work of a legislator.” And in her 1951 essay “Where Paine Went Wrong,” Cecilia Kenyon wrote rather coolly:

Had the French Revolution been the beginning of a general European overthrow of monarchy, Paine would almost certainly have advanced from country to country as each one rose against its own particular tyrant. He would have written a world series of Crisis papers and died an international hero, happy and universally honored. His was a compellingly simple faith, an eloquent call to action and to sacrifice. In times of crisis men will listen to a great exhorter, and in that capacity Paine served America well.

This is to forget that Paine went to France as an official American envoy, not as an exporter of revolution. It also overlooks Paine the committee man and researcher, Paine the designer of innovative iron bridges and the secretary of conventions. The bulk of part 2 of The Rights of Man is taken up with a carefully costed plan for a welfare state, the precepts and detail of which would not have disgraced the Webbs, for example:

Having thus ascertained the probable proportion of the number of aged persons, I proceed to the mode of rendering their condition comfortable, which is.

To pay to every such person of the age of fifty years, and until he shall arrive at the age of sixty, the sum of six pounds per ann. out of the surplus taxes; and ten pounds per ann. during life after the age of sixty. The expense of which will be,

| Seventy thousand persons at £6 per ann. | 420,000 | |

| Seventy thousand ditto at £10 per ann. | 700,000 £1,120,000 |

This decidedly pedestrian scheme was dedicated to the equestrian Marquis de Lafayette—a man who more closely resembled the beau ideal of Madame Roland’s freelance incendiary.

Paine was even able to rebuke his greatest antagonist for his lack of attention to formality:

Had Mr. Burke possessed talents similar to the author of “On the Wealth of Nations,” he would have comprehended all the parts which enter into and, by assemblage, form a constitution. He would have reasoned from minutiae to magnitude. It is not from his prejudices only, but from the disorderly cast of his genius, that he is unfitted for the subject he writes upon.

This argument from Adam Smith is not the style of a footloose firebrand.

Che Guevara, who was bored to tears at the National Bank of Cuba, once spoke of his need to feel Rocinante’s ribs creaking between his thighs. If Paine ever felt the same, then he stolidly concealed the fact. A large part of his revolutionary contribution consisted of using the skills he gained as an exciseman. “The bourgeoisie will come to rue my carbuncles,” said Marx on quitting the British Museum. The feudal and monarchic predecessors of the bourgeoisie actually did come to regret teaching Paine to count and to read and to reckon, even to the paltry standard required of a coastal officer.

You may see the doggedness (and, sometimes, the accountancy) of Paine in numerous passages—almost as if he were determined to justify Burke’s affected contempt for “the sophist and the calculator.” The prime instances are the wrangle over slavery and the Declaration of Independence, and the negotiation over the Louisiana Purchase. Both involved a correspondence with Thomas Jefferson, which has, unlike much of Paine’s writing, survived the bonfire made of his papers and memoirs.

Jefferson withdrew a crucial paragraph from the Declaration, consequent upon strenuous objection from Georgia and South Carolina. In its bill of indictment of the king, it had read:

He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating and carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere, or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. This piratical warfare, the opprobrium of INFIDEL powers, is the warfare of the CHRISTIAN king of Great Britain. Determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought and sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or restrain this execrable commerce. And that this assemblage of horrors might want no feet of distinguished dye, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them by murdering the people on whom he has obtruded them, thus paying off former crimes committed against the LIBERTIES of one people with crimes which he urges them to commit against the LIVES of another.

In his earlier pamphlet against slavery, Paine had written:

These inoffensive people are brought into slavery, by stealing them, tempting kings to sell subjects, which they can have no right to do, and hiring one tribe to war against another, in order to catch prisoners … an hight of outrage that seems left by Heathen nations to be practised by pretended Christians… . That barbarous and hellish power which has stirred up the Indians and Negroes to destroy us; the cruelty hath a double guilt—it is dealing brutally by us and treacherously by them.

Either Paine actually wrote the vanquished paragraph or, as William Cobbett said of the Declaration itself, he was morally its author. His biographer Moncure Conway, who fairly tends to find the benefit of any doubt, comments on the excision and summons an almost Homeric scorn to say:

Thus did Paine try to lay at the corner the stone which the builders rejected, and which afterwards ground their descendants to powder.

Conway and Paine both half-believed that revolutionaries make good reformists, a belief obscured by the grandeur of Conway’s phrasing.

Anyway, Paine was not always to be Cassandra. As elected clerk to the Pennsylvania Assembly, he labored hard on the preamble to the act which abolished slavery in that state. He is generally, but not certainly, credited with its authorship. At any rate, his clerkly efforts gave him the satisfaction of seeing the act become law on March 1, 1780, as the first proclamation of emancipation on the continent.*

More than two decades later, on Christmas Day, 1802, Paine wrote to Jefferson with a well-crafted suggestion of another kind.

Spain has ceded Louisiana to France, and France has excluded the Americans from N. Orleans and the navigation of the Mississippi: the people of the Western Territory have complained of it to their Government, and the government is of consequence involved and interested in the affair. The question then is—what is the best step to be taken?

The one is to begin by memorial and remonstrance against an infraction of a right. The other is by accommodation, still keeping the right in view, but not making it a groundwork.

Suppose then the Government begin by making a proposal to France to repurchase the cession, made to her by Spain, of Louisiana, provided it be with the consent of the people of Louisiana or a majority thereof… .

The French treasury is not only empty, but the Government has consumed by anticipation a great part of the next year’s revenue. A monied proposal will, I believe, be attended to; if it should, the claims upon France can be stipulated as part of the payments, and that sum can be paid here to the claimants.

I congratulate you on the birthday of the New Sun, now called Christmas day; and I make you...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright page

- Dedication page

- Contents

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Prepared for the Worst by Christopher Hitchens in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.