- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

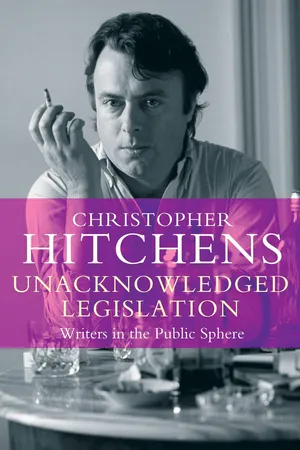

Unacknowledged Legislation is a celebration of Percy Shelley's assertion that 'poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world'. In over thirty magnificent essays on writers from Oscar Wilde to Salman Rushdie, and with his trademark wit, rigour and flair, master critic Christopher Hitchens dispels the myth of politics as a stone tied to the neck of literature. Instead, Hitchens argues that when all parties in the state were agreed on a matter, it was the individual pens that created the space for a true moral argument.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CONTENTS

Foreword

I. ‘In Praise of …’

The Wilde Side

Oscar Wilde’s Socialism

Lord Trouble

George Orwell and Raymond Williams

Oh, Lionel!

Age of Ideology

The Real Thing

The Cosmopolitan Man

After-time

Ireland

Stuck in Neutral

A Regular Bull

Not Dead Yet

II. ‘In Spite of Themselves …’

Old Man Kipling

Critic of the Booboisie

Goodbye to Berlin

The Grimmest Tales

The Importance of Being Andy

How Unpleasant to Meet Mr Eliot

Powell’s Way

Something about the Poems

The Egg-head’s Egger-on

Bloom’s Way

III. ‘Themes …’

Hooked on Ebonics

In Defence of Plagiarism

Ode to the West Wing

IV. ‘For Their Own Sake …’

O’Brian’s Great Voyage

The Case of Arthur Conan Doyle

The Road to West Egg

Rebel in Evening Clothes

The Long Littleness of Life

V. ‘Enemies List …’

Running on Empty

Unmaking Friends

Something For the Boys

The Cruiser

Acknowledgements

Index

FOREWORD

WRITING IN RESPONSE to Thomas Love Peacock, who had said that ‘a poet in our time is a semi-barbarian in a civilised community’, Percy Bysshe Shelley proclaimed in 1821 that:

Poets are the hierophants of an unapprehended inspiration; the mirrors of the gigantic shadows which futurity casts upon the present; the words which express what they understand not; the trumpets which sing to battle, and feel not what they inspire; the influence which is moved not, but moves. Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world. [Italics mine.]

The fate of his polemic In Defence of Poetry (which is customarily pared down to comprise only the last sentence of the above paragraph) is not untypical of the fate of radical freelance work in all ages. The magazine to which it was sent, and which had printed Peacock’s original remarks, ceased publication almost as soon as the riposte had been composed. Shelley then hoped to publish it in the pages of The Liberal, a periodical launched by Byron and Leigh Hunt. But The Liberal, too, expired in the grand tradition of noble-minded and penurious reviews. Shelley died long before his essay saw print. His widow, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, got it into publication eighteen years after his decease, omitting several of the references to Peacock. Thus, we owe our too-easy familiarity with an attenuated aperçu to the belated efforts of the author of Frankenstein, who was also the daughter of the authors of Political Justice and A Vindication of the Rights of Women.

Frankenstein’s unhappy creation allows me an easy transition to the following, which was written by W. H. Auden in August 1968. (August 1968, following Auden’s fondness for numinous dates like 1 September 1939, is also the title of the poem):

The Ogre does what ogres can,

Deeds quite impossible for man,

But one prize is beyond his reach,

The Ogre cannot master Speech.

About a subjugated plain,

Among its desperate and slain,

The Ogre stalks with hands on hips

While drivel gushes from his lips.

This was penned in hot and immediate response, from just across the Austrian frontier, to the Soviet erasure of culture and democracy in Czechoslovakia in that very month. I happened to be in Havana at the time and on my way to Prague, and was very much struck – without registering it anything like so acutely – by the awful rhetoric and terminology employed by defenders of the Warsaw Pact invasion. The hideous term ‘normalisation’, a sort of apotheosis of the langue du bois, was the name given to the subsequent ‘restoration of order’.

Twenty-one years later, the mighty occupation-regime installed by the full weight of Panzerkommunismus (Ernst Fischer’s caustic word for it) collapsed amid laughter and ignominy, without the loss of a single life, as a consequence of a civil opposition led by satirical playwrights, ironic essayists, Bohemian jazz-players and rock musicians, and subversive poets. Life in the Czech lands, and the Slovak lands too, may since have become much more banal and, so to say, prosaic. But would it be merely ‘romantic’ to say that Auden, in 1968, had been somehow aware of ‘the gigantic shadows that futurity casts upon the present’? ‘Moved not’, or not so much as moving, he had prefigured the end of a system which depended on gibberish and lies. The sword, as we have reason to know, is often much mightier than the pen. However, there are things that pens can do, and swords cannot. And every tank, as Brecht said, has a crucial flaw. Its driver. Suppose that driver has read something good lately, or has a decent song or poem in his head …

Invited recently by the Los Angeles Times to contribute to one of those symposia on ‘Politics and the Novel’, I was asked to name the works of fiction that had had most influence upon me. Novels were specified; even so I should have said ‘the war poems of Wilfred Owen’. These are neither novels and nor, in one important sense, are they fictional or imaginary. But I shall never be able to forget the way in which these verses utterly turned over all the furniture of my mind; inverting every conception of order and patriotism and tradition on which I had been brought up. I hadn’t then encountered, or even heard of, the novels of Barbusse and Remarque, or the paintings of Otto Dix, or the great essays and polemics of the Zimmerwald and Kienthal conferences; the appeals to civilisation written by Rosa Luxemburg in her Junius incarnation. (Revisionism has succeeded, in many cases justly, in overturning many of the icons of Western Marxism; this tide, however, still halts when it confronts the nobility of Luxemburg and Jean Jaurès and other less celebrated heroes of 1914 – such as the Serbian Dimitri Tucovic.) I came to all these discoveries, and later ones such as the magnificent Regeneration trilogy composed by Pat Barker, through the door that had been forced open for me by Owen’s ‘Dulce Et Decorum Est’. So it’s highly satisfying to read again his poem ‘A Terre (Being the Philosophy of Many Soldiers)’ and to come across the lines:

Certainly flowers have the easiest time on earth.

‘I shall be one with nature, herb and stone’, Shelley would tell me.

Shelley would be stunned: The dullest Tommy hugs that fancy now.

‘Pushing up daisies’ is their creed, you know.

A true appreciation of Shelley; to find a dry and ironic use for him in the very trenches. Most of Owen’s poetry was written or ‘finished’ in the twelve months before his life was thrown away in a futile action on the Sambre-Meuse canal, and he only published four poems in his lifetime (aiming for the readers of the old Nation and Athenaeum, and spending part of his last leave with Oscar Wilde’s friend and executor Robert Ross, and with Scott Moncrieff, translator of Remembrance of Things Past). But he has conclusively outlived all the jingo versifiers, blood-bolted Liberal politicians, garlanded generals and other supposed legislators of the period. He is the most powerful single rebuttal of Auden’s mild and sane claim that ‘Poetry makes nothing happen’.

The essays in these ensuing pages were all written in the last decade of the twentieth century; between the marvellous humbling of the Ogre and the onset of fresh discontents. They do not engage with political writers so much as with writers encountering politics or public life. I don’t deal exclusively or even principally with poets either, but I have looked for those who try and raise prose to the level of poetry (from Wodehouse and Wilde, to Anthony Powell’s ear for secret harmonies and unheard melodies). Another and more blunt way of stating my own ambition is to recall Orwell’s desire to ‘make political writing into an art’. Sometimes, and less strenuously, I have attempted to show how some artists have almost involuntarily committed great political writing.

The intersection where this occurs is an occasion of paradox, or of epigram and aphorism. One still pays attention when Wilde says that socialism, properly considered, would free us of the distress and tedium of living for others. And one lends an ear when Orwell – so crassly termed a ‘saint’ by V. S. Pritchett – announces that saints must always be adjudged guilty until proven innocent. Lionel Trilling once alluded to ‘the bloody crossroads’ where literature and politics meet, and this phrase was annexed by the dire Norman Podhoretz (who is to Trilling as a satyr to Hyperion) for the title of a notorious and propagandistic book. But properly understood and appreciated, literature need never collide with, or recoil from, the agora. It need not be, as Stendhal has it in Le Rouge et Le Noir, that ‘politics is a stone tied to the neck of literature’ and that politics in the novel is ‘a pistol shot in the middle of a concert’. The openly, directly politicised writer is something we have learned to distrust – who now remembers Mikhail Sholokhov? – and the surreptitiously politicised one (I give here the instance of Tom Wolfe) is no great improvement. Gabriel Garciá Márquez has paid a high price for his temporal allegiances, as have his patient readers. But in the work of Tolstoy, Dickens, Nabokov, even Proust, we find them occupied with the political condition as naturally as if they were breathing. Which is what Auden must also have meant when he wrote, in obeisance to a man whose public opinions he actively distrusted, (‘In Memory of W. B. Yeats’: February 1939):

Time that is intolerant

Of the brave and innocent,

And indifferent in a week

To a beautiful physique,

Worships language and forgives

Everyone by whom it lives;

Pardons cowardice, conceit,

Lays its honours at their feet.

Time that with this strange excuse

Pardoned Kipling and his views,

And will pardon Paul Claudel,

Pardons him for writing well.

Nothing is lost, from these verses, in contemplation of the fact that Auden removed them, and many other exquisite poems and passages, from his own canon in a boring attempt to re-establish himself as a man of Anglican integrity. (Also, the rehabilitation of Paul Claudel may take a little longer than he surmised.)

I cannot apologise for the fact that my subjects are almost all English or American or Anglo-American. For one thing, I am mainly English and have no real competence in any other tongue. For another, the Anglo-American idiom is well on its way to being what Kipling and others always hoped for, albeit in a different guise: a world language. A world language, that is, without being an imperial one. (Indeed, at least in some ways, the first to the extent that it has ceased to be the second.) The written record of English literature is also a powerful and flexible instrument for the understanding of British and perhaps post-British society – a point to which I want to recur. While in America, the role of the writer is given exceptional salience by the fact of the United States being a ‘written’ country, based on a number of founding documents that are subject to continuous revision and interpretation. No clause in the Constitution mandates an opposition party; indeed the whole document is designed to evolve orderly consensus. But the First Amendment, which places freedom of expression on a level with freedom of (and freedom from) religion, grants the writer wide powers. In my graduate class on ‘Unacknowledged Legislators’ at the New School in New York, which gave me the title of this book, I sought to show how often, when all parties in the state were agreed on a matter, it was individual pens which created the moral space for a true argument. Some chief instances would be Thomas Paine on the issue of independence and anti-monarchism, Garrison and Douglass on slavery, Mark Twain and William Dean Howells on imperialism, and Upton Sinclair and John Steinbeck on the exploitation of labour. But nearer to our own time, there was the disruption by Norman Mailer and Robert Lowell of the unspoken agreement on a war of atrocity and aggression in Indochina. And of course, we have Gore Vidal’s seven-volume novelisation of American history, a literary attempt at the creation of what he terms ‘a usable past’.

Although admittedly borne around the globe partly on the shoulders of a homogenising American commerce, another way in which English has become a language of universals is the form in which it has been annexed by its former colonial subjects. Here, the critical figure has been Salman Rushdie. Ever since his magnificent evocation of combined partition and parturition in Midnight’s Children, he has been raising a body o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- About the Author

- Also by Christopher Hitchens

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Unacknowledged Legislation by Christopher Hitchens in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Essays. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.