![]()

CONTENTS

Maps

Introduction

I 2000–800 BC

From Bronze Age to Dark Age

II 800–725 BC

Competing for glory

Olympics and the Olympian gods

III 725–700 BC

From Homeric hero to Hesiod’s peasants

IV c. 700–593 BC

Tyranny, poetry and speculation

V 593–493 BC

Athens: from tyranny to democracy

VI 493–450 BC

From Persian empire to Athenian – tyranny?

VII 450–421 BC

Athens v. Sparta: the Peloponnesian War

VIII 421–399 BC

Athens capitulates: the execution of Socrates

IX 399–362 BC

City-states at war in Greece

X 360–336 BC

The rise of Macedon: Philip II takes over Greece

XI 336–322 BC

Alexander the Great and the end of democracy

XII 322–229 BC

After Alexander: the empire divided

XIII 229–146 BC

Macedon falls to Rome

XIV 146–27 BC

The end of Alexander’s empire

Epilogue: the survival of Greek literature

Reading list

Index

A note on the author

![]()

MAPS

![]()

INTRODUCTION

If the Greek philosopher Plato is to be believed, the story of this book goes back 12,000 years – all the way to Atlantis. But he was making that story up, so it goes back a mere 3,000 years or so, from the Minotaur’s Crete and the Trojan War to the Olympic Game (yes: it all started with just the one), the invention of our alphabet, the West’s very first literature (the epics of the Iliad and Odyssey), the Persian wars, the subsequent ferocious conflict for mastery of Greece between Athens and Sparta, the emergence of Philip II of Macedon and his son Alexander the Great, Alexander’s conquest of the East as far as India, and the gradual collapse of that ‘empire’ before the unstoppable march of that new power to the West – Rome. It ends in 27 BC, when the last piece of Greek territory receives a Roman governor.

Further along that sometimes inspiring, sometimes dispiriting way, the immense influence of the ancient Greeks on our world will emerge. At almost every point of Western thinking about politics, literature, mathematics, art, architecture, drama, philosophy, education, war, sex, medicine, cosmology, astronomy, biology, the body, the emotions, ethics, linguistics, death, logic, race, slavery, history, quite apart from the wonderful worlds of myths and oracles, the Greeks are somewhere there.

The book (for the title Eureka!, see p. 79) adopts the same format as my Veni Vidi Vici (Atlantic Books, 2013). Each chapter begins with a timeline and a broad summary of the chapter’s contents, followed by a series of brief ‘nuggets’, some fleshing out the summary, others digressing into different areas of interest.

But the contrast with Veni Vidi Vici will soon become apparent. The history of Rome offers a coherent story of one highly influential city that, between 700 BC – AD 500, came to dominate much of Europe, North Africa and the Near East. But neither Athens nor Sparta nor any other Greek community ever dominated as Rome did.

As a result, the ancient Greek world lacks such intense focus. Consequently, while this account will be chronological, it will not tell a single story, but concentrate on the various differing big players as they emerge over the centuries, and over the Mediterranean too. For the Greeks, who mistrusted the sea, were still great adventurers, always on the lookout for the main chance and new experiences, and they established cities all over the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. That said, there will be a bias towards Athens, because for all its disappointments after its glory years in the fifth and fourth centuries BC, its achievements at that time still electrify the imagination.

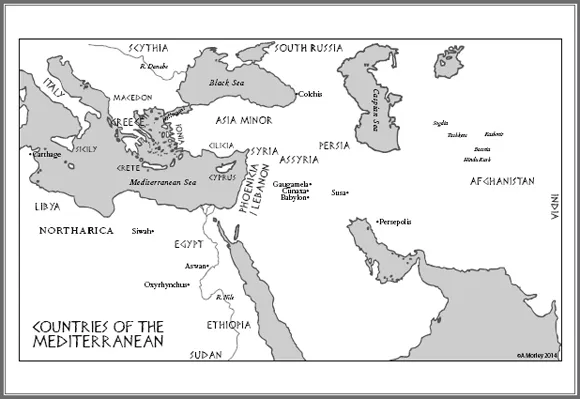

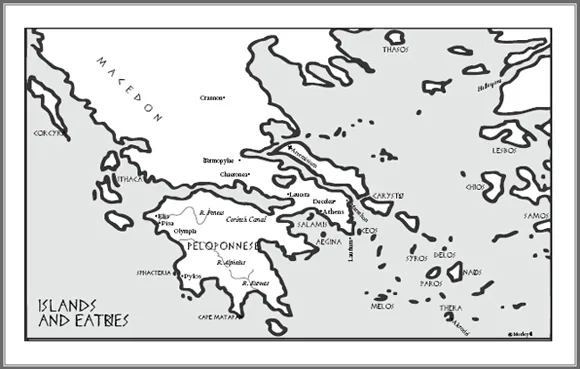

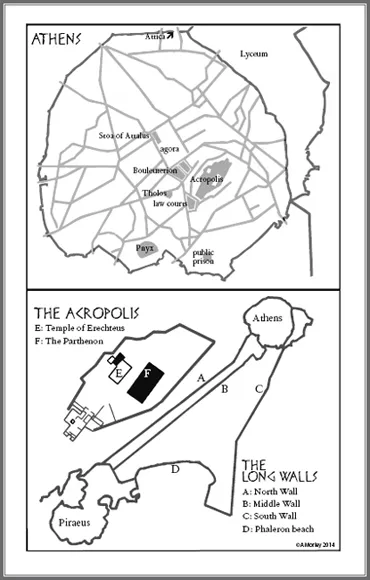

Jeannie Cohen (she and I run the charity Friends of Classics) read the whole book in its various forms and made countless improvements. I am most grateful to Martin West for permission to use his superb translations of Hesiod (Hesiod: Theogony, Works and Days, Oxford, 1988) and the Greek lyric poets (Greek Lyric Poetry, Oxford, 1993) and, as ever, to Andrew Morley for the maps.

Peter Jones

Newcastle on Tyne

June 2014

![]()

NAMES AND NUMBERS

GREEK NAMES

Greek names in English have, by historical convention, been adapted from Latin. Sometimes they are virtually identical in the three languages: Greek Periklês, Latin Pericles, English Pericles. At other times, the Greek and Latin are similar, but the English different: Greek Aristotelês, Latin Aristoteles, but English Aristotle. Sometimes the Latin (and so the English) are very different from the Greek: Thoukudidês, Thucydides, Thucydides (pronounced ‘Thewsiddiddees’).

Note that the Greek long ô was pronounced ‘or’, and the Greek long ê was pronounced ‘air’. So Hellênes was pronounced ‘Hellairness’, arkhôn ‘arkhorn’. On this convention, see my An Intelligent Person’s Guide to the Classics (Bloomsbury 1999, Appendix 1).

The long mark ^ is applied only to transliterated Greek words in italics, not to their English form. Thus Periklês, exactly representing the Greek, but Pericles in English. Observe that the Greek k becomes the English c (drakhma: drachma), and the Greek u becomes the English y (Olumpikos: Olympic).

GREEK MONEY, WEIGHTS AND DISTANCES

Obol[os] is the lowest unit of money:

6 oboloi = 1 drakhma, lit. ‘handful’

100 drakhmai = 1 m(i)na

60 m(i)nai = 1 talent

These are related to the weight of the coins. On the Attic standard, an obol is about 0.72 grams, a drachma 4.31 grams, a mina 431 grams (about 1 lb), a talent 25.86 kg (about 60 lb). Other cities adopted different weight standards.

VALUE OF MONEY

As ever, there are no meaningful correspondences between ancient Greek money and ours. One calculation suggests that, for a family of four in Athens c. 400 BC, the cost of living varied from 2.5 to 6 obols a day (see p. 178-9 on pay for jury service and p. 247 on pay for attending the Assembly). The pay for a skilled craftsman varied from 6 to 9 obols (1 to 1.5 drachmas) a day.

DISTANCES

These are given in modern measurements, roughly equivalent to the Greek ones. Thus the 200 metres of the first Olympic game (p. 37) represent one stadion in Greek (whence ‘stadium’).

![]()

WHO WERE THE GREEKS?

When ‘ancient Greeks’ are being discussed, it is usually assumed that they are people who live in Greece. But Greeks did not think of themselves first and foremost in that way. What made them Greek, as the historian Herodotus tells us in the fifth century BC, was not their location but their shared stock, language, culture and gods (but not politics, interestingly). And Herodotus meant it, because Greeks established settlements all over the Mediterranean, ‘like frogs around a pond’ (as Plato put it), without compromising their Greekness.

So to talk of ‘ancient Greece’ and ‘ancient Greeks’, is not to imply a politically unified country and people as in, for instance, ‘England’ and ‘the English’, but people who spoke Greek and lived, in their own separate, autonomous Greek communities, not only on the Greek mainland but also (in time) in Asia Minor (roughly modern Turkey), the Black Sea, the Near East, parts of North Africa, southern Italy, Sicily and the coastal regions of southern France (Gaul) and Spain. Nor did their common heritage mean they all lived in harmony. On the Greek mainland, in particular, these independent communities – Athenians, Spartans, Thebans, Corinthians and so on – were regularly at each other’s throats.

Hint: every time you come across a place-name, find it on the map. That will make the point most forcefully that not all Greeks lived in Greece, let alone in Athens. Greeks lived and worked all over the place. Indeed, Greeks living on the west coast of Asia Minor (Turkey) were, arguably, the originators of ‘the Greek miracle’.

Finally, and rather surprisingly, Greeks did not call themselves ‘Greeks’: they called themselves Hellênes and their country Hellas (see p. 46), and still do. Why, then, do we call them ‘Greeks’ and say they lived in ‘Greece’? Because of the Romans, as usual, who were captivated by Greek language and culture and transmitted so much of it to us. They called the people Graeci (‘Gr-eye-kee’) and the country Graecia, and we anglicized the Roman forms into ‘Greeks’ and ‘Greece’.

And why did the Romans call them that? We do not know, but see p. 79 for two possible guesses.

![]()

I

2000–800 BC

TIMELINE

2000–1600 BC | Minoan Crete – the golden age |

c. 1600 BC | The explosion of Minoan Thera |

1600–1150 BC | Late Bronze Age; the rise and fall of ‘Mycenaean’ Greeks |

1450 BC | Mycenaeans move into Knossos |

1400 BC | (Greek) Linear B writing |

1350 BC | Knossos destroyed |

c. 1200 BC | Mycenaean attack on Hisarlik? |

c. 1150–800 BC | End of Bronze Age society and culture; the Dark Ages |

![]()

FROM BRONZE AGE TO DARK AGE

This is a much debated period of history because we have virtually no written sources for it. Two peoples and one site will dominate the greatly simplified story of the Bronze Age world presented here: Minoan Cretans; Mycenaean Greeks; and Hisarlik, a site of major importance in what is now north-west Turkey (Asia Minor) at the entrance to the Dardanelles.

Crete at this period is called ‘Minoan’ merely because ...