![]()

CONTENTS

| Author’s Note |

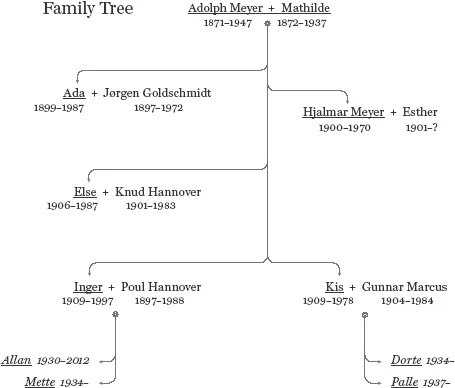

| Family Tree |

| | |

| Prologue |

| Chapter 1: | SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 26: The Last Day of the Past |

| Chapter 2: | MONDAY, SEPTEMBER 27: At Home |

| Chapter 3: | TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 28: The Message |

| Chapter 4: | WEDNESDAY, SEPTEMBER 29: Departure |

| Chapter 5: | THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 30: The Escape |

| Chapter 6: | FRIDAY, OCTOBER 1: The Action |

| Chapter 7: | SATURDAY, OCTOBER 2: The Transfer |

| Chapter 8: | SUNDAY, OCTOBER 3: Ystad |

| Chapter 9: | MONDAY, OCTOBER 4: The Village of Ruds Vedby |

| Chapter 10: | TUESDAY, OCTOBER 5: Going North |

| Chapter 11: | WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 6: Gilleleje |

| Chapter 12: | THURSDAY, OCTOBER 7: The Hope |

| Chapter 13: | FRIDAY, OCTOBER 8: The Beach at Smidstrup |

| Chapter 14: | SATURDAY, OCTOBER 9: Realities |

| Epilogue |

| | |

| Notes |

| Bibliography |

| Index |

![]()

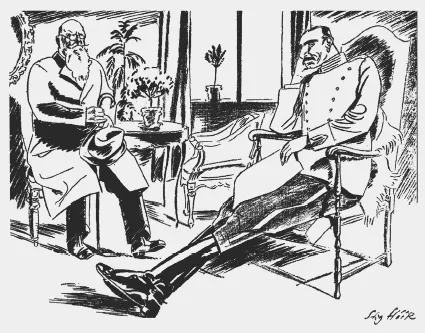

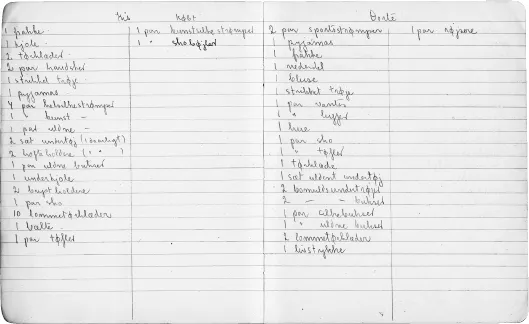

This cartoon in the Göteborg Trade and Maritime Journal gave birth to a widespread and long-lived myth that King Christian rode through the streets of Copenhagen wearing the yellow star in defiance of Nazi demands that the Jews do so.

The drawing shows the Danish prime minister, Thorvald Stauning, in an overcoat, in thoughtful conversation with King Christian, easily recognizable by his riding boots and uniform. In the caption Stauning asks: “What shall we do, Your Majesty, if Scavenius says that our Jews also have to wear yellow stars?” The king replies: “Then we’ll probably all wear yellow stars”—an almost literal transcription of an interview King Christian had had with Acting Prime Minister Vilhelm Buhl four months earlier. The fact that the tenacious myth is rooted in a real conversation has only been revealed recently, as the handwritten diary notes made by the king were made accessible to historians. Even if King Christian was prepared to do so, he did not ride through the streets of Copenhagen wearing the yellow star; in fact no one in Denmark was required to wear it.

Cartoon by Norwegian Ragnald Blix, January 10, 1942

AUTHOR’S NOTE

THE BIRTH OF A MYTH

Toward the end of the conversation the acting prime minister raised the question of the Jews. He had come to confer with the aging king Christian X on the state of affairs in occupied Denmark. It was early September 1941, and the German advance into the Soviet Union seemed successful and unstoppable, the news going from bad to worse. The European continent was under totalitarian control, and the United States remained firmly neutral. Denmark insisted on its neutrality, too, but the country had been under German occupation since April 1940, and even if the firm Danish rejection of any Nazi representation in government was still holding up, the Germans were becoming more and more arrogant in their demands. Now Finance Minister Vilhelm Buhl, acting as head of government, sounded out the king on the delicate issue of the Danish Jews. Later the same day the king wrote down the main lines of the conversation in his private diary. According to the king, the finance minister expressed deep concern: “Considering the inhuman treatment of the Jews not only in Germany but also in other countries under German occupation, one could not help but worry that one day this request would also be presented to us. If so, we would have to reject it outright following their protection under the Constitution.”

The king agreed “that [he] would also reject such demands in regard to Danish citizens. If the request was made, the right attitude would be for all of us to wear ‘the star of david.’ The Finance Minister interjected that that would indeed be a way out.”1

Buhl did not keep the king’s suggestion to himself, and four months later the conversation appeared as the text of a cartoon in a newspaper in neighboring Sweden, also neutral but not occupied by the Germans. The cartoon gave birth to the compelling image of King Christian riding the streets of occupied Copenhagen wearing the yellow star. The myth has never died, and new generations have taken it as a token of hope amid the dismal history of the Holocaust.

The history from the Swedish cartoon traveled widely and it proved both compelling and useful. It served those in the United States and the United Kingdom who were working to improve the public image of an occupied Denmark criticized for its cowardly appeasement of Hitler’s Germany. In the United States the myth was spread by Danish-American and Jewish organizations, in the United Kingdom by the Political Warfare Executive as part of a targeted effort to drive a wedge between Denmark’s allegedly pro-German government and the resistance-willing people rallying behind their king.

The myth, of course, is false. But the history behind it is even more fascinating: Not only did the king not wear the yellow star, but no one in Denmark did. The very attitude of the king and his prime minister, as reflected in their brief conversation—and indeed that of the entire people—prevented any provision in regard to Jews being passed in Denmark. This is what makes Denmark a unique example, an exception to the general picture of the Holocaust. The exception was more fundamental than the myth reveals. It went beyond the rejection of measures directed against the Jews by denying the very existence of a Jewish question. It simply stated the obvious: That before being of Jewish descent, these individuals were Danish citizens or at least protected by Danish law, which did not distinguish between citizens of different creeds. There was simply no issue—and thus there could be no measures to address it.

![]()

COUNTRYMEN

![]()

PROLOGUE

She went through the packing lists one more time. Somehow doing so comforted her. The children’s clothes, Gunnar’s, her own. They needed to be warm and practical and not take up too much space. Still, they also needed to look right. The whole thing seemed at once urgent and unreal. And she had no idea what to do. So she sat down to make packing lists. To establish a measure of normality in what suddenly seemed not to be normal at all. A few days later she noted: “We were optimistic, and couldn’t and wouldn’t believe that as Danes we could come to experience the horrors that Jews in the other German-occupied countries had gone through. From the middle of September the rumors began to circulate that persecution of the Jews would come, and we were nervous when Jewish books and records were stolen from offices of the Jewish congregation where they were kept. We lulled ourselves into a certain kind of calm thinking that maybe they would limit themselves to new laws and the like. And even though we heard about many of our own race who didn’t sleep at home for fear of being picked up by the Gestapo at night, we stayed at home until Sunday, September 26.”1

That was the last night for a long time that Kis Marcus slept in her own bed. The next morning she began a journey into the realm of uncertainty. Over the following days it would take her and her immediate family to parts of the country they had not previously known, and into situations they would not have conceived of as possible just a few days before. At the same time they would embark on a mental journey from being law-abiding and well-respected citizens to being cast as criminals wanted by German patrols for deportation to an unknown fate. During her escape, Kis Marcus took notes for her diary. She struggled to keep track of events, sequences, and emotions. Maybe she also struggled to stay aloof from the situation and to keep her emotions at bay. She wrote about the fear, the doubts, the confusion, and the hardships as well as about her fellow travelers and the children. She wrote about the uncertainty and—eventually—about the relief.

Kis and her family traveled with her twin sister, Inger, her husband, Poul Hannover, and their two children. Poul Hannover also kept a diary, as did his son Allan, who noted events from the perspective of an alert thirteen-year-old.

While the two small families headed south, the twin sisters’ father, Dr. Adolph Meyer, headed north together with thousands of other refugees. The prominent pediatrician had declared that he would stay in Denmark until he was certain that his entire, numerous family was safe in Sweden. This hesitation proved to be almost fatal, as the doctor faced hardship and danger while he searched desperately for a safe route to Sweden. Adolph Meyer also kept a diary, and his meticulous records provide, together with his exchange of letters the following weeks with those who helped him escape, a rare firsthand account of the reflections and actions of those directly affected by the attempt to round up the Danish Jews. Eventually the doctor survived, and like his daughter, son-in-law, and grandson, he soon took the time to look over his notes and write an account of the dramatic getaway

When the family returned to Denmark after the war, the four diaries were kept as a private testimonial to the ordeal, shared only among members of the family and trusted friends. Now, as the last of the young children participating in the escape are themselves aging, the family has decided to share these accounts with a wider public—realizing that they constitute singular contemporary and personal witness to the making of a miracle. Here the experience of a wife and mother, another by a well-connected businessman, a third by a sharp-eyed young teenager, and the last by an aging patriarch of stature and influence—all describe the dramatic impact of sudden discrimination and persecution. Together with the few other known contemporary accounts, these diaries open the door into the mind-sets of both the refugees and their persecutors—and into that of the Danish helpers. Though each story is unique, their experiences were similar. It’s a story thousands recognize, both then and today. A story of doubt, of despair—and of the determination to survive.

The history of the escape of the Danish Jews is but a small part of the much larger history of the Holocaust. But it does teach a lesson of self-preservation, of defiance, and of support from countrymen turning against the deportation in indignation and anger. In this way it is also the history of a society upholding its own view of what was right and what was wrong—even as it bowed before the superior force of German occupation.

Poul Hannover finishes his diary at Stadshotellet in Västerås, west of Stockholm, on October 10, 1943. He writes of his objective: “After I managed to get hold of a typewriter on Wednesday, I started to write down my memories of the trip—the most terrible trip I’ve ever experienced or ever hope to experience. This is not a novel—no fancy trimmings—it is for ourselves and our closest friends and family—I do not think others should read it.” Like many other refugees, he felt no inclination to share his experience, and for the rest of his life, he kept his notes close. Some gladly told their stories after the war. But most did not, and Poul Hannover comments on this ambiguity: “As I begin to write down what happened in the last days, I ought to clarify why I’m doing it—and for whom. I know neither. I just feel the need to get this down on paper, incomplete though it surely is. I also don’t know what others experienced—if it’s more or less—but for us it seems, because we have experienced the unbelievable, that if I don’t get this down, there will be barely anyone who will believe it.”2

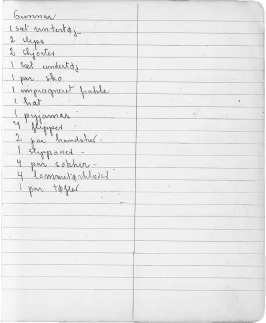

What do you do if escape is the only way out? What do you take along, and what do you leave behind?

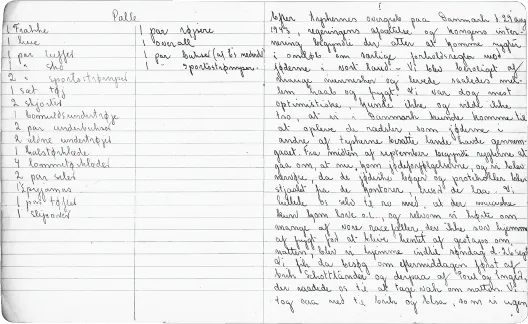

Kis Marcus was thirty-four years old and the mother of two small children when these urgent questions arose. Until then she had always been safe, and she had no experience of persecution or of being on the run. While her thoughts developed and she tried to decide what to do, she began to prepare, writing down what each of the family’s four members should pack if necessary. Committing it to paper helped focus her mind, and in the following days Kis Marcus set the unfolding events down in black softcover notebooks.

But the notebook’s first pages are perhaps the most telling: no narrative and no comments, only a list of the essentials, odd bits and pieces representing the daily life of her family and constituting the total of what she hoped to bring along from her previous life. Everything else had to be left behind, and it is as if her drawing up the packing lists was the beginning of her separation from the house, the furniture, and countless other items, big and small. The nonessentials.

Kis Marcus was already a refugee.

Private family collection

2323__perlego__chapter_divider...