- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

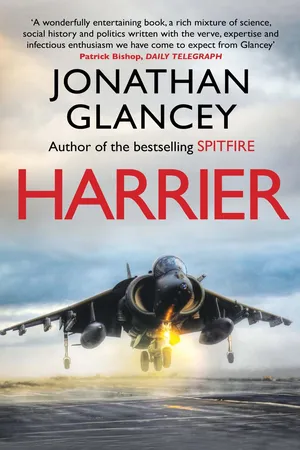

The British designed and built the Harrier, the most successful vertical take-off-and-landing aircraft ever made. Combining state-of-the-art fighter plane technology with a helicopter's ability to land vertically the Harrier has played an indispensable role for the RAF and Royal Navy in a number of conflicts, most famously the Falklands War.

Jonathan Glancey's biography is a vividly enjoyable account of the invention of this remarkable aeroplane and a fitting tribute to the inspiration and determination of the men and women who created it, and the bravery of the men who flew it, often in the most dangerous conditions.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

A LEAP OF IMAGINATION

When I was a schoolboy, one of my friends lived in Kingston upon Thames. The last stage of the long journey to this prosperous Surrey outpost was by the 65 bus from Ealing Broadway. This was operated by London Transport’s handsome and beautifully engineered RT double-deckers – buses that, resplendent in their guardsman’s outfits of red, black and gold, ran all but faultlessly through London streets and country lanes around the capital for forty years. The route was fascinating for any young person alert to interesting architecture, engineering and history. The RT would gargle steadily past Ealing Library – originally Pitzhanger Manor, a house rebuilt in an imaginative classical style from 1800 by John Soane, architect of the original Bank of England – on the way to the factories at Brentford, where, allegedly, Julius Caesar had forded the Thames in 55 BC, and so along to Kew Bridge and its pumping station built for the Grand Junction Waterworks Company in 1838. Inside, there brooded one of the largest of all Cornish beam engines, a ‘monster’ according to Charles Dickens, built to pump water to London, which it did for very nearly a century. Luckily it has been preserved, and you can gawp at it, in steam, at Kew today.

From here, the bus picked up speed to Richmond, before threading cautiously through the town’s narrow shopping streets and then giving a tantalizing glimpse of the Thames as we skirted Richmond Bridge, a graceful spring of stone arches across the tidal river designed by the architects James Paine and Kenton Couse, Secretary to the Board of Trade, in the 1770s. South of Richmond, and on to Ham and Petersham, the bus entered a stretch of genteel suburbia resembling rolling countryside, picking up and dropping off passengers to the accompaniment of the conductor’s bell in an enchanting realm of fine Georgian villas, before making its stately way down a long straight road to Kingston.

And here, all of a sudden, was what I used to think of as one of the most awe-inspiring and special buildings within reach of my beloved St Paul’s Cathedral. It was the principal façade and offices of the Hawker factory, Kingston upon Thames, a commanding, part-classical, part-modern design, rather like the 1930s Underground stations designed by Charles Holden, although writ on a much larger scale that spoke eloquently of the confidence and nobility of British manufacturing industry. To make it all the more exciting, I knew that behind that palatial façade, and its great stretch of steel windows, Harrier jump jets were being built for the RAF, the Royal Navy, the US Marine Corps and other armed forces abroad that clearly knew that British was still best. This will sound hopelessly naïve today, yet until the end of the 1960s, it was still possible to feel a part of a Britain that appeared to be able to design and make wonderful things on its own back. Of course, things had changed, although nothing prepared me for my return to that long straight road leading down to Kingston upon Thames when I came this way in 2012 to meet Ralph Hooper at the old Hawker social club set between the factory and the Thames.

The RT buses had long gone, replaced by heavy, noisy, ugly provincial buses with squealing brakes bought off-the-peg from God-only-knows where and appearing to cock a snook at London, its history and design culture at every turn of their loutish wheels. What had also gone on Richmond Road was the Hawker factory itself. This came as a shock, and not least because this great workplace and its grand façade had been replaced by a dismal estate of the most banal and indifferent homes, a development careless of architecture and urban design. Here was a story, all too graphically expressed by these new buildings, of how Britain had turned its back on manufacturing industry and engineering prowess wherever possible over the past forty years. The blame for this has partly, and with justification, been laid at the door of Margaret Thatcher’s Tory governments from 1979. And yet, Mrs Thatcher would never have been voted into office a second time by such a sweeping margin without British victory in the Falklands War and without the Harriers, built here in Kingston upon Thames, where the vapid new housing estate now stood in all its gormlessness.

On my journey down to Kingston, I read an article from the Surrey Comet, dating from 7 March 1959. ‘For almost half a century,’ it began, ‘Kingston has been closely associated with the aircraft industry and lays proud claim to being the birthplace of machines which bear some of the most famous names in the history of military aircraft. Mention the name of Hawkers and one phrase springs immediately to mind – renowned fighter aircraft. In all the successes and setbacks that have attended it since its early days, the people of Kingston have come to look upon the Company as an organisation in which they can take personal pride. The admiration is not one-sided: it is matched by the regard which the Company has for the town.’

The litany of fighter aircraft built by Hawker at Kingston is indeed a wonder: Hart, Fury, Hurricane, Typhoon, Tempest, Sea Fury, Sea Hawk, Hunter, Hawk and, of course, Harrier, all of these under the design direction of the brilliant Sydney Camm. At times in the 1930s, eight in ten RAF aircraft were one of the powerful fighter biplanes designed by Camm in Kingston. The Hawker legacy, however, stretched back further than these legendary piston-engined and jet fighters. Hawker had been founded by Tommy Sopwith – or, to give him his full name, Sir Thomas Octave Murdoch Sopwith (1888–1989) – in partnership with Harry Hawker (1889–1921), who had been chief engineer and test pilot for the Sopwith Aircraft Company, which had been wound up, after great success in the First World War, by a punitive government tax called the Excess War Profits Duty and by the simple fact that thousands of its new fighters were no longer needed.

Sopwith was a debonair, Kensington-born sportsman who taught himself to fly in 1910 in a Scottish Aeroplane Syndicate Avis, a 40 hp JAP-engined machine that resembled the aircraft Louis Blériot, the French aviator and engineer, had designed, built and flown across the English Channel in 1909, the first pilot to do so. Sopwith founded his first aircraft company in 1912 when he was just twenty-four years old. His biographer, Bruce Robertson, wrote:

Sopwith had four great assets: a private income from his father [a successful civil engineer]; a bevy of devoted sisters conveniently placed socially and geographically; a mechanical aptitude fostered by an education in engineering and certainly not least, an abundance of pluck and drive.

His friends included the pioneer British aviator Charles Rolls, who was soon to team up with Henry Royce, A. V. Roe and Hugh ‘Boom’ Trenchard, the legendary, and famously loud, ‘Father of the RAF’. Young Sopwith could hardly have fallen in with a more influential, brilliant and effective crowd.

Sopwith taught Boom to fly. He also taught Harry Hawker, a young Australian and blacksmith’s son who had sailed to England in 1910 in search of work in the fledgling aviation industry. After brief stints with the Commer Car Company and the English branches of Mercedes and Austro-Daimler, Hawker was taken up by Sopwith in June 1912. He flew solo after three lessons and became not just the Sopwith Company’s first test pilot, but also the first professional British test pilot. Sopwith built two Wright-style aircraft at Brooklands that year before founding his own factory in an old ice-skating rink close to Kingston station. A highly competitive sailor as well as a pilot, Sopwith was also a skilled ice-skater and a member of the British national ice-hockey team. Beginning with the Sopwith Bat flying boat designed with S. E. Saunders in 1913, the new company responded immediately to the demands, and opportunities, of the Great War. Hawker had already designed the Sopwith Tabloid, a small, fast and lively biplane that, in seaplane guise, won the 1914 Schneider Trophy held that year at Monaco; its fastest two laps were timed at 92 mph.

Significantly for the future of the company, single-seat variants of the Tabloid flew with both the Royal Flying Corps and the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) during the First World War; significantly, too, they were employed as fighters, scouts and bombers. In fact, two RNAS Tabloids flying from Antwerp on 8 October 1914 made the first British aerial bombing raids over Germany. In August 1915, one of the Schneider seaplane variants of the Tabloid was launched from the carrier HMS Campania; it was a close call, with even this lightweight aircraft finding it hard to take off despite the ship steaming hard and fast into the wind. And yet, it was not long before Campania was sailing with Sopwith Pups, Babies and 1½ Strutters on board, all of them able to operate successfully from the ship’s 245-foot flight deck. In 1917, the Pup became the first aircraft to land on a moving ship.

Sopwith employed a staff of five thousand during the war and, working with a wide network of subcontractors, produced 18,000 aircraft between 1914 and 1918. These included 1,850 Pups, 5,500 1½ Strutters and no fewer than 5,747 Camels. The Camel was a demanding machine but, along with the superb German Fokker DVII, it became one of the most effective and best-known fighters of the Great War. In fact, 60 per cent of British single-seat aircraft produced by the time of the German surrender on 11 November 1918 were Sopwiths. During the conflict these machines also flew with the French, Belgian and American military, by which they were much appreciated and greatly admired. The many other aircraft types produced at Kingston during the Great War included the Buffalo, Bulldog, Cuckoo, Hippo, Salamander and Snipe, their entertaining names prompting those within and without the industry to refer fondly to the ‘Sopwith Zoo’.

Sopwith himself was a remarkable fellow. An enthusiastic sportsman, who raced cars and yachts, and who at the age of ten had accidentally shot and killed his father in a hunting accident on a Scottish island, he built his own J-Class yachts in the 1930s, designed in collaboration with Charles Nicholson, to compete in the America’s Cup. He was at the helm of one of these beautiful boats, Endeavour, in June 1940, sailing to pick up British troops stranded on the beaches at Dunkirk. As its chairman, he oversaw the creation of the Hawker Aircraft Company in 1920 and remained a consultant with Hawker Siddeley and British Aerospace until 1980. Sopwith was always very much up to date with the very latest, and often futuristic, developments. A fifteen-year old when the Wright Brothers took to the air with The Flyer, he went on to oversee Sopwith Pups and Camels, Hawker Furies, Hurricanes, Typhoons and Hunters. One of the first men in Britain to hold a pilot’s licence, he lived to see Concorde soar across the Atlantic at Mach 2, men land on the Moon and, best of all from his point of view, one of his company’s aircraft take off vertically. Interviewed in 1979 by Sir Peter Allen, president of the Transport Trust, Sopwith was asked: ‘On looking back, which of your planes were you proudest of? Would it be the Camel, or something later, say one of the later Hawker Siddeley machines?’ He shot back: ‘I would say, undoubtedly, the Harrier… the Harrier flies forwards, backwards, sideways. Once I’d seen an aeroplane fly backwards under control, I thought I had seen everything.’

Sadly, Harry Hawker, who lent his name to the superb line of fighter aircraft that ended with the jet-powered Hawk and Harrier, was killed in July 1921 when he crashed a Nieuport Goshawk at Hendon while practising for the Aerial Derby – a race of 200 miles over two laps with turning points at Brooklands, Epsom, West Thurrock, Epping and Hertford, and won at 163 mph on a blisteringly hot summer’s afternoon by Jimmy James, in jacket and tie, flying a Gloster Mars I. Hawker, who would have given James a run for his money, may well have suffered a haemorrhage while pulling a high-g turn and died while attempting to land.

As it was, the Hawker Aircraft Company bought the Gloster Aircraft Company in 1934, and merged with the automotive concern Armstrong Siddeley and its aircraft subsidiary Armstrong Whitworth the following year. Hawker Siddeley then took over A. V. Roe (as in Avro and Lancaster). Until 1963, however, Hawker aircraft were marketed under their own name, as were the products of other Hawker Siddeley subsidiaries. British aircraft manufactured in the 1960s as diverse as the Blackburn Buccaneer, Gloster Javelin, de Havilland Sea Vixen, Folland Gnat and Avro Vulcan were all Hawker Siddeley products, as were the Blue Streak, Red Top and Sea Dart missiles. Railway locomotives, metro trains and Westinghouse brakes and signals were too. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, a Canadian railway industry Hawker Siddeley subsidiary built new trains for the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority; other MBTA trains at the time were built by Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm, a fascinating case of old wartime sparring partners turning swords into ploughshares.

Throughout this long and convoluted history, and even into the era when, in 1977, Hawker Siddeley was made a part of state-owned British Aerospace (BAe, later privatized in 1981), Sopwith remained a consultant to the aviation giant he had spawned in Kingston in that former ice-skating rink two years before the outbreak of the First World War. His centenary was celebrated with an appropriate military fly-past, and he died at the age of 101. Intriguingly, William Manning, the engineer who had built the Avis machine Sopwith learned to fly on in a workshop in Battersea, went on, after a spell working with Fiat on the racing seaplanes of the 1930s, to a research post at the Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough, where he was co-inventor of the probe-mounted valve that allowed the Harrier, among other RAF aircraft, to refuel in mid-air.

The RAF has flown Sopwiths and Hawkers made in Kingston from its inception in 1918 to the present day: the Harrier may have bowed out in 2010, yet the Hawk trainer, developed from 1968 by a design team led by Ralph Hooper and John Fozard, and first flown in 1974, is still in production. It serves with the RAF and many other air forces around the world and has been the choice of the virtuoso RAF Red Arrows display team since 1979. The Hawk, though, is not built in Kingston; the factory closed in 1992, to be replaced as we have seen by that other great British product, horrid housing.

But back to the Surrey Comet of 1959:

A huge new office block housing the Company’s administrative section, design and pre-production departments has been built on the Richmond Road frontage… for all its size it does not obtrude but enhances the landscape, hiding as it does the gaunt factory buildings to which it is attached.

And its grandeur notwithstanding, this was not a luxurious building:

Plainly, almost austerely, panelled in oak, the boardroom, situated centrally on the first floor, is flanked on each side by the offices of the directors and their immediate staff. On the other side of the corridor is a department which is a source of great pride to the Hawker team – the design section under Sir Sydney Camm. He is able to step across from his offices and see an army of experts at work on many various projects.

The design section is where Ralph Hooper and his colleagues worked. Their open-plan office covered 50,000 square feet under a 400-foot span ‘daylight roof’.

The county newspaper was giving me a very good idea of what it might have been like to work here in the heyday of the transformation of the experimental P.1127 into the world’s first successful V/STOL fighter jet, the Harrier. ‘There is,’ the article went on, ‘an almost monastic calm in the design office and thus it is a dramatic moment for the visitor when he is conducted through the double doors to a platform overlooking the factory floor. Contrasting the cloistered quiet of the office is the din of the Hunter production floor.’ This was ‘Aircraft Factory No. 1’, built by the government and used by Sopwith throughout the First World War. It was meant to have been a temporary structure, but endured until 1992. The P.1127 is not mentioned in the newspaper article except in reference to work being carried out on ‘a vertical take-off machine’ in a new 11,000-square-foot Research and Development building facing the Thames behind the factory. Significantly, though, the Surrey Comet noted a new ‘computing section’ next to the design department in which the ‘most expensive piece of furniture’ was ‘a £40,000 electronic computer which works out problems that could not be attempted by mere humans’. In 1959, the average salary of a ‘mere human’ in Britain was a little under £900.

That new company computer is a reminder of the fact that the design of P.1127 pre-dated the digital age. Most of the design work on the jump jet was done with pencils, paper and slide rules, and on drawing boards. In fact, when later in 2012 I spoke to test pilots of the Lockheed Martin F-35B, they all made the point that, as far as they were concerned, the Harrier – which they all knew and most had flown in combat – was a distinctly analogue aircraft, while the F-35B, its much bigger and hugely more complex successor, is digital.

I met Ralph Hooper at the former Hawker social club. The club, now a local authority sports centre, is where ex-Hawker employees still gather. Hooper, who lives within walking distance of the club, is tall, alert, drily and even sardonically witty, and not a man given to unnecessary reminiscence. Like so many engineers, he seems as if he might have no time for anything like small talk. He wondered what on earth we might talk about given that the story of the Harrier had been told so many times and suggested that, if I had the patience, I could find everything I needed to know in a library. When I explained that I was as interested in the politics that had shaped, driven, buffeted and undermined the Harrier and in the tortured story of twentieth-century British manufacturing, Hooper then sat down and duly proceeded to reminisce until we agreed that mutual exhaustion had set in. Modest British engineers like Hooper, and the many others I have met over the years, seem to be wholly unaware of the fact that meeting them face-to-face is an honour. And, unlike architects, for example, they do not talk about themselves without a good deal of prompting.

Libraries can indeed fill in the gaps. Ralph Spenser Hooper, lead designer of the P.1127 and chief designer of the Harrier until 1965, was born in Hornchurch, Essex in 1926. In 1933, the family moved to Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire. Hooper’s father was a civil servant with the Board of Trade, and his mother, a nurse in the First World War, was a descendant of Edmund Spenser, the author of the epic Elizabethan poem, The Fairie Queene. The young Ralph Hooper, however, was more interested in Meccano construction sets – he connected his alarm clock to the bedroom light-switch – and his Hornby trains; his grandfather was a rolling-stock draughtsman with the London and North-Eastern Railway at Stratford Works, London. Ralph made model aeroplanes and was apprenticed, in 1941, to Blackburn Aircraft based at Brough, a few miles west along the Humber from Hull. At the time, the company – later also absorbed into Hawker Siddeley – was working on the Firebrand, a powerful if problematical Fleet Air Arm fighter just too late to see service in the Second World War.

Hooper spent two years in Blackburn’s workshops, a further two years studying aeronautics at University College, Hull and a final year in Blackburn’s offices. His apprenticeship complete, he went on to the new College of Aeronautics at Cranfield, Bedfordshire – where he learned to fly, going solo in a Tiger Moth after four hours and twenty minutes’ instruction – and from there to a job with Hawker’s experimental drawing office. He had, he says, been thinking of working for Vickers at Brooklands because the factory was close to the Surrey Gliding Club at Redhill, of which he was now an active member, but, as fate had it, Sydney Camm offered five shillings a week more than Vickers was prepared to pay, and that settled the matter.

At Hawker, the first project Hooper worked on was the P.1052, the forerunner of the graceful, successful and long-lived Sea Hawk, the company’s first jet, which served with the Fleet Air Arm and several foreign navies in front-line service until 1983, when India finally replaced its examples with Sea Harriers. After the Sea Hawk, Hooper worked on the P.1067, the future Hawker Hunter, one of the most graceful of all military jets. No fewer than 1,972 were made, and although English Electric Lightnings replaced the RAF’s Hunter F.6 interceptors in 1963, four Hunters were still in service with the Lebanese Air Force in 2013. The next project, the P.1121, was a supersonic fighter shot down by the Duncan Sandys White Paper. Hawker’s Ron Williams, meanwhile, was hard at work on designs for the highly ambitious P.1129, the company’s proposal for a replacement for the RAF’s English Electric...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- List of illustrations

- Preface

- Introduction: To tread upon the air

- 1 A leap of imagination

- 2 Kestrel breeds Harrier

- 3 Cold War warrior

- 4 Baptism at sea

- 5 Foreign legions

- 6 New wars for old

- 7 Wing feathers clipped

- 8 What flies ahead

- Epilogue: The Windhover

- Acknowledgements

- Select bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Harrier by Jonathan Glancey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.