![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

John Breuilly

Introductory remarks

At the end of the eighteenth century, Germany was an idea in the minds of some intellectuals and statesmen and a phrase in the title of a loose association of states: the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation. In 1918, Germany was a tightly organized state and society which had just lost a war of unprecedented scale and destruction against the other major world powers. In 1800, most Germans lived in the countryside and agriculture dominated the economy. By 1918, Germany was an urban society and industry had overtaken agriculture. In 1800, most people travelled by foot and communicated by word of mouth. By 1918, there was mass transportation by rail and road; telegraph, telephone, cinema, letter writing and a mass print media had transformed communication.

It is difficult to provide a comprehensive description and interpretation of German history over this period. Emphasizing long-term transformations, as I have just done, can lead to neglect of the experiences of particular groups and individuals which do not fit into that pattern of change, a pattern which can consequently take on an air of inevitability. To switch attention to such experiences risks fragmentation, incoherence and the loss of any sense of large-scale change over several generations. To gain some hold on the range and diversity of experiences, actions and outcomes, historians must select particular topics and approaches which in turn exclude other topics and approaches. There can be no ‘total history’ and no definitive interpretation.

This volume makes no such claims. The sheer scope of the subject makes it impossible for any one historian to do justice to different periods and themes. The range of expertise assembled in this collection is intended to provide the reader with a sense of the distinctive ways in which social, economic, political and cultural historians work, without privileging one period, theme or approach within this ‘long century’ over any other.

Chapters 2 to 7 addresses the period from the end of the eighteenth century to 1871. Chapters 2, 3, 6, and 7 focus on politics, war and revolution. Whaley and Clark consider a range of mainly political and military topics between roughly 1780 and 1815, and 1815 and 1848, respectively, each questioning interpretations which viewed the period from the perspective of national unification under Prussian leadership. Siemann analyses the revolutions of 1848–9 in terms of different levels of action, critical of the one-dimensional view of the revolutions as a ‘failure’. In my chapter, I propose an argument about how the situation after the revolution created conditions for a chain of events culminating in the improbable success of Prussia in founding the German Second Empire.

For the whole of this period, Köhler provides a comprehensive overview and analysis of its cultural and intellectual history, while Lee surveys critically influential interpretations of economic and social history.

Chapters 8 to 12 moves on to the German Second Empire. Brophy analyses the political institutions and history of the Second Empire until Bismarck’s resignation in 1890. Hewitson takes up similar issues from 1890 until the outbreak of war in 1914. Chickering considers the history of the Second Empire from the outbreak of war until its defeat and collapse in late 1918.

Two further chapters deal with the cultural and intellectual, and the social and economic history of this period. Jefferies surveys the cultural and intellectual history of this first German nation state, while Berghan looks at the social and economic transformations of the Second Empire.

Chapters 13 and 14, we turn to two perspectives on German history for the whole of the ‘long nineteenth century’ which have become increasingly important for historians. Frevert, building on the considerable body of work on women’s history, writes on nineteenth-century Germany as gendered history. Lindner, drawing upon recent transnational perspectives on national history, looks at German mass emigration, the German pursuit of empire and the ways in which these impacted on Germany.

Finally, in a new Conclusion, I draw on all these chapters to suggest a way of connecting together many of the changes which took place in the German lands between the late eighteenth century and the end of the First World War.

These chapters are best described as essays. Each contributor offers a point of view, an argument, not a descriptive survey or an encyclopaedia entry. The essays are not hermetically sealed from each other. Instead, they overlap and disclose different, even conflicting, views of a subject. Given that there can be no ‘a single-authored book.

![]()

Chapter 2

The German lands before 1815

Joachim Whaley

In the decades before 1815, the German lands underwent a process of revolutionary change, but there was no revolution as such, nothing to compare with events in France in 1789. Yet, contemporaries experienced this period as one of profound and rapid transformation. Most obviously, the map of Germany in 1815 looked very different from what it had been in, say, 1780. The Holy Roman Empire had ceased to exist after a thousand-year history; a bewildering patchwork of several hundred quasi-independent territories had been replaced by forty-one sovereign states in a loose confederation.

This ‘territorial revolution’ was accompanied by other equally profound changes: the transformation of political and legal institutions; a new relationship between church, state and society in the Catholic regions; new social and economic structures resulting from the massive transfer of Catholic ecclesiastical property; new cultural attitudes and novel perceptions of what ‘Germany’ and the very identity of the Germans was or might be; a new political vocabulary and new concepts with which Germans described the world in which they lived. The sheer magnitude and pace of change struck many contemporaries as the major characteristic of their age. The Gotha bookseller and publisher Friedrich Perthes (1772–1843) expressed the sense of many when he reflected in 1818 that while previous periods in history had been characterized by gradual change over centuries, ‘in the three generations alive today our own age has, in fact, combined what cannot be combined. No sense of continuity informs the tremendous contrasts inherent in the years 1750, 1789 and 1815; to people alive now … they simply do not appear as a sequence of events.’1

Much of this complexity was lost in the classic accounts of this period by German historians of the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They constructed a narrative which showed the inevitability of the emergence of a Prussian-dominated nation state in 1871. For Treitschke and others, German history was Prussian history. The Holy Roman Empire was portrayed as decayed and moribund, and the German territories as backward and corrupt. When challenged by the ideas and the armies of the French Revolution, German political institutions, both imperial and territorial, collapsed. Yet out of Napoleon’s humiliation of the Germans, according to the traditional view, a new sense of German destiny arose. Prussia, which had emerged as a great power under Frederick the Great, became the focus of a new national movement, while the Prussian reforms after 1806 supposedly embodied the German answer to 1789. Most leading historians, like Friedrich Meinecke (1862–1954), held that Stein and Hardenberg transformed Prussia into a bastion of the German national movement, the driving force in the Wars of Liberation which defeated Napoleon and finally expelled the French from Germany.

Elements of the traditional view survive even in some modern surveys. Thomas Nipperdey’s account of Germany in the nineteenth century (published in 1983) opens with the words, ‘In the beginning was Napoleon’.2 Nipperdey cannot be accused of being an exponent of the kleindeutsch tradition of Prusso-centric history. Yet, his portrayal of Napoleon as the ‘creator’ echoes the teleological ideology of the nationalist historians. German nationalism is presented as a response to French domination characterized by a reaction against French ideas (the ‘ideas of 1789’), the problematic inception of modernity in Germany.

Tradition dies hard, but in the last sixty years, virtually every aspect of the period before 1815 has been a subject of revision. Some scholars have explored the ‘modernization’ of Germany in this period. Others, working primarily from an early modern perspective, have found continuity as well as change. Above all, much recent research has sought to investigate alternatives to the Prusso-centric view of German history. The insistence that the emergence of the Prussian–German nation state in 1871 was not inevitable has focused attention on other options, such as a Holy Roman Empire or the Confederation of the Rhine. This has in turn shed new light on the history of nationalism and on the significance of reform movements outside Prussia, particularly in southern and western Germany.

At the same time, a growing emphasis on lines of continuity, from the enlightened absolutist reform before 1789 to the bureaucratic reforms after 1800, has challenged the view that the modernization of the German states, including Prussia, was purely defensive. Furthermore, in the European context, it appears increasingly that revolutionary France rather than reforming Germany was the exception. Some aspects of this tendency to ‘normalize’ German history before 1815 may be as much a reflection of the Zeitgeist of the Federal Republic since the 1980s and 1990s as the Prusso-centric view was of the political ideology of Germany between 1871 and 1945. Yet, recent research has done much to undermine the view that German history between 1780 and 1815 represents a stage in a straightforward progression towards the nation state, still less a Sonderfall with disturbing implications for the history of the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The Holy Roman Empire in the eighteenth century

The Prussian–German tradition viewed the Holy Roman Empire as inadequate because it failed to become a nation state. Modern scholars, by contrast, argue that the system worked effectively. Under the emperor as Schutz- und Schirmherr (protector and guardian), the Reich fulfilled a vital role after 1648 in the areas of law, defence and peace in Central Europe. As a Friedensordnung (a peace-preserving order), it both guaranteed the peace and stability of Europe as a whole and ensured the survival of the myriad small German territories, none of which, except Prussia, were capable of survival as independent units in the competitive world of European powers. As a Verteidigungsordnung (a system of defence), the Reich ensured protection from external threat. As a Rechtsordnung (a legal system), it provided mechanisms to secure the rights both of rulers and, more extraordinarily, of subjects against their rulers. Its institutions, such as the imperial courts in Wetzlar and Vienna, provided legal safeguards for many of the inhabitants of the German territories.

Conditions varied enormously among the territories which made up the Reich. Some were characterized by corruption, mismanagement and stagnation. Many of the smaller south German imperial cities, the miniature territories of imperial knights or independent abbeys and the like, were incapable of significant innovation even if the will to change was there. In many territories, however, the decades after 1750 saw significant changes. Inspired by enlightened rationalism and dri ven by the need for revenue, particularly acute during the economic crisis which followed the end of the Seven Years’ War in 1763, many German princes embarked on ambitious reform programmes. Even in the ecclesiastical territories, commonly regarded as anachronisms by the end of the eighteenth century, wide-ranging reforms were introduced in education, poor relief and administration generally. Other territories made a start with the codification of law and the rationalization of fiscal administration. As the term ‘enlightened absolutism’ indicates, though the term should really be ‘enlightened government’ since no German prince wielded absolute power, the process was initiated by the princes, but it was driven and implemented by a growing army of educated officials. For many of them, the reforms represented the first stage of the emancipation of society that formed a central ideal of the German Enlightenment (Aufklärung). In the upheavals after 1800, the inherent contradiction between absolutism and emancipation became glaringly apparent. Yet, in this first phase, there was periodic tension but little conflict. The German educated classes were not composed of disaffected intellectuals, but of active and often enthusiastic participants in the reform process (see Map 2.2).

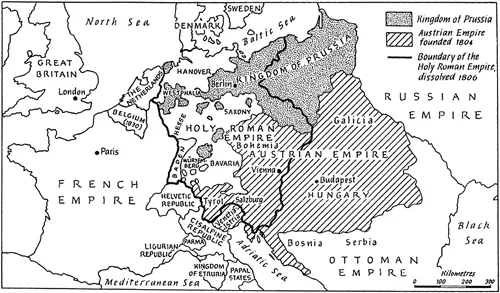

Map 2.1 German Central Europe in 1792.

Source: Brendan Simms, The impact of Napolean: Prussian High Politics, Foreign Policy and the Crisis of the Executive, 1797–1806 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

Map 2.2 Germany and the Austrian Empire, 1800–6.

There were, of course, limits to what could be achieved by even the most ambitious enlightened prince. The most significant constraint was the imperial system itself. The German princes were not sovereign rulers: their power was qualified by a feudal subordination to the Reich which guaranteed the status quo, especially the rights of estates and corporations which in many territories impeded the imposition of rationalized central control. This limitation was only seriously challenged in the Habsburg lands and in Prussia, with fundamental implications for the future of the Reich and for the subsequent history of German lands.

From the early eighteenth century, Habsburg policy was characterized by a growing tension between dynastic interests and imperial duties. The succession crisis of 1740 underlined the need to consolidate the Habsburg inheritance, a collection of territories which straddled the southeastern frontier of the Reich. The creation of a Habsburg unitary state meant removing the western Habsburg lands from the Reich. In Austria, therefore, enlightened reform aimed to construct a closed unitary state, which under Joseph II from the late 1770s involved introducing policies hostile to the Reich, in particular a plan to exchange Bavaria for the Netherlands (with or without the consent of the Bavarian estates). Joseph only succeeded in uniti...