![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

Trusty’s Hill Fort rests on the summit of a craggy knoll within the Boreland Hills, in the Stewartry district of Dumfries and Galloway (NX 5889 5601). The site lies in the parish of Anwoth, approximately 1 km south-west of the centre of Gatehouse of Fleet (Fig. 1.1). It is a key heritage asset of the Fleet Valley National Scenic Area. At a height of 72 m OD this is not the most prominent summit of the Boreland Hills, an area of small hillocks covered in scrub and rough grazing for cattle and sheep (Fig. 1.1). However, it affords wide views over the Fleet valley. Higher peaks of the Boreland hills rise to the south-west partially blocking the view of the Fleet Bay.

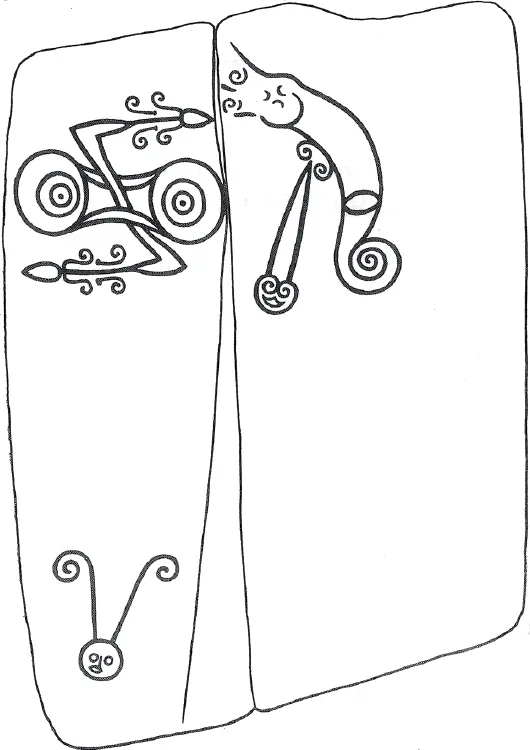

The fort is defined by a vitrified rampart around the summit of the hill, enclosing an area of 0.0437 ha, with an outer bank and rock-cut ditch on its northern side and a series of lesser outer ramparts on its southern side. It is particularly conspicuous amongst the hillforts of Galloway for the pair of Pictish symbols, comprising a double disc and Z-rod, and a sea-monster and sword, carved on an exposed face of greywacke bedrock at the entrance to the fort. These symbols, their unique character and their location in south-western Scotland have long puzzled scholars.

The site is first mentioned in the Anwoth parish entry in the Statistical Account of Scotland as ‘one of those vitrified forts which have lately excited the curiosity of modern antiquaries’ (Gordon 1794, 351). It was observed that the summit of this steep rock was ‘nearly surrounded with an irregular ridge of loose stones, intermixed with vast quantities of vitrified matter’ and that ‘on the south side of this fort there is a broad flat stone, inscribed with several waving and spiral lines, which exhibit however no regular figure’ and ‘near it likewise were lately found several silver coins; one of King Edward VI; the rest of Queen Elizabeth’ (ibid.). The site was again noted just over 50 years later in the New Statistical Account of Scotland, but with no further information (Johnstone 1845, 378).

The first written reference to the place-name of Trusty’s Hill was given in the Ordnance Survey Name Book for Kirkcudbrightshire (Ordnance Survey 1848, 26). The surveyor verified the name through four local residents and recounts an interesting story about the origins of the name. The surveyor states that ‘formerly there had been a house at the base of the hill which had been occupied by a man named Carson who had married one of the minister’s servants, which servant the minister had always styled her as his Trusty Servant, from whom it is said the hill took its name’ (ibid.). The Name Book also states that the hill, which was on the farm of Boreland, had originally been called the ‘Cairn of Borland’, though the surveyor makes no mention of a cairn, simply adding that ‘on its summit is the vitrified fort’ (ibid.). Unfortunately, available mapping evidence from the late sixteenth century to the middle of the nineteenth century shows neither Cairn of Borland or a cottage in the vicinity of Trusty’s Hill and so it is difficult to verify this story.

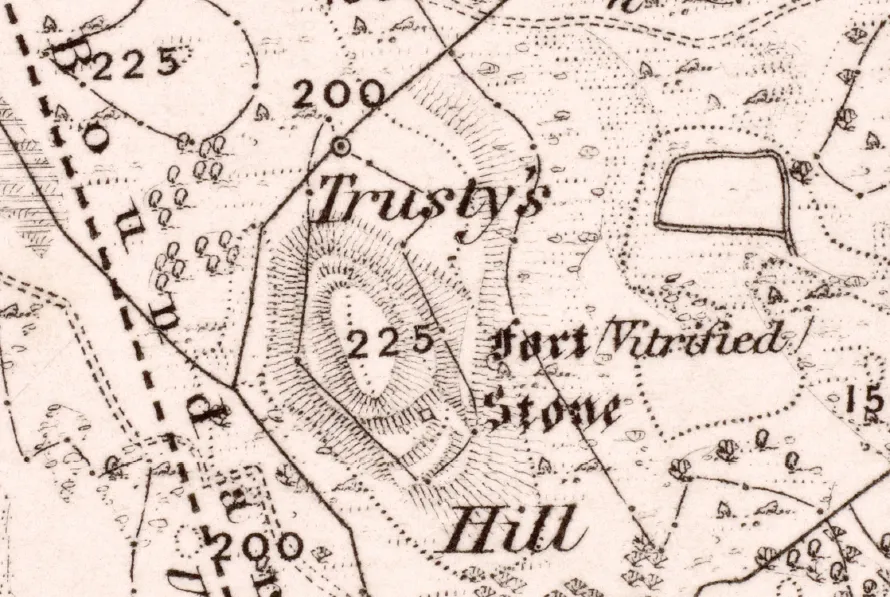

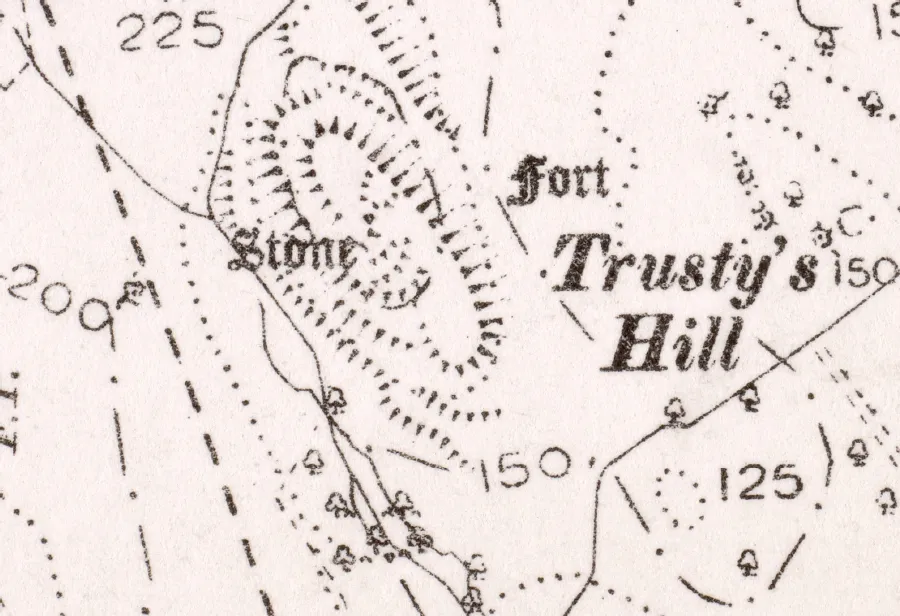

The first survey of the site was undertaken in 1848 by the Ordnance Survey for the First Edition 6-inch map, published in 1854 (Fig.1.2). However, while the basic shape of the fort is recognisably correct, much of the finer detail is missing. The subsequent Second Edition plan of the site produced by the Ordnance Survey in the 1890s is even less detailed, the surveyors appearing to have abandoned the premise of a small hilltop citadel in favour of a larger oval enclosure. This depiction ignores many of the topographical and archaeological features present (Fig. 1.3).

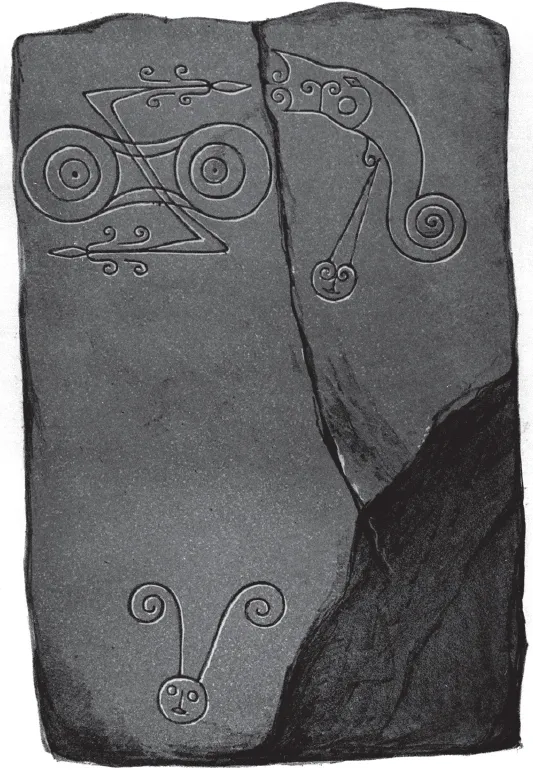

The carved symbols were first drawn by John Stuart (Fig. 1.4), who also recorded that the site went by the name of Trusty’s Hill (1856, 31). Stuart doubted whether the horned head at the bottom was nothing but a more recent addition to the other carvings (ibid.).

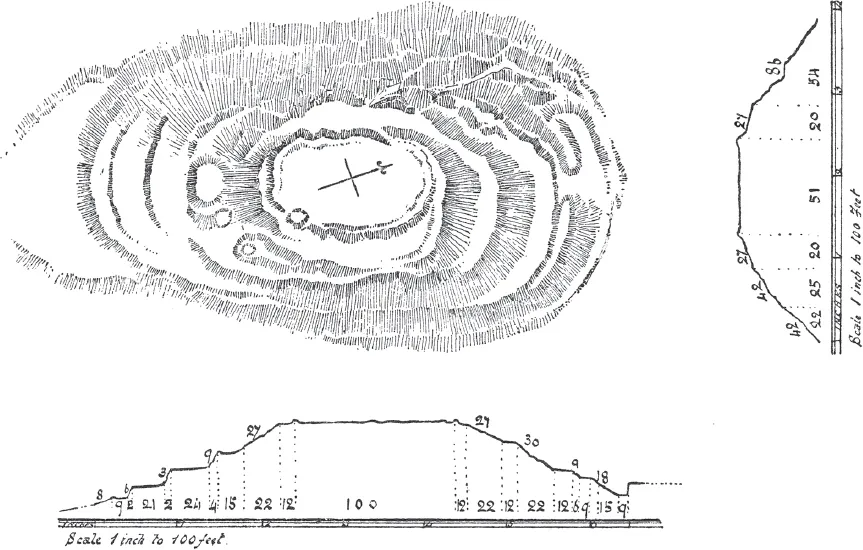

The first detailed plan of the site (Fig. 1.5) was in fact made around the same time as the Ordnance Survey Second Edition map in the 1890s by Frederick Coles, who recorded un-mortared stonework around the summit but noted that according to ‘accurate observers’ the walls were regular and compact, and exhibited vitrification 40 or 50 years previously (1893, 173–4). The style of Coles’s depiction contrasts with that used by the Ordnance Survey but it reflects the archaeological features and the craggy, broken topography of the site somewhat better.

Fig. 1.2. Ordnance Survey First Edition 6-inch (1:10,560 scale) 1854 map. © Courtesy of RCAHMS (Ordnance Survey Historical Maps). Licensor www.rcahms.gov.uk

Fig. 1.3. Ordnance Survey (1:2500 scale) 1896 map. © Courtesy of RCAHMS (Ordnance Survey Historical Maps). Licensor www.rcahms.gov.uk

Of most interest to Coles were the ‘Dolphin’ and ‘Sceptre and Spectacle Ornament’ carvings. He concurred with Stuart in dismissing the lowest figure as of recent origin (Coles 1893, 174). Coles also noted that he could not find cup and ring marks said to be near this sculpturing. Interestingly, he suggested that the antiquity of the name Trusty’s Hill could be dismissed as the invention of a certain Allan Kowen, who 50 years before, according to local testimony, had rented a small croft near the foot of the hill and founded the legend about ‘Trusty’ (ibid.). While this statement suggests a slightly different albeit modern origin to the name from that recounted in the 1848 Ordnance Survey Name Book, by the 1890s the fame of the inscribed stone and the fort may have led to the invention of a local mythology which was not apparent earlier in the century. Certainly much of the graffiti exhibited on the stone (see Fig. 1.12) appears to be nineteenth century in date and points to the site having been something of a local attraction.

Fig. 1.4. Stuart’s 1856 depiction of the Pictish Symbols at Trusty’s Hill. © Courtesy of RCAHMS. Licensor www.rcahms.gov.uk

The Pictish symbols at Trusty’s Hill were included a short time later in John Romilly Allen and Joseph Anderson’s survey of Early Christian Monuments in Scotland (1903, 477–78; Fig 1.6), who classified the z-rod and double disc symbol and dolphin symbol as Class I (1903, 92). They were the first to note the protective cage of iron bars over the carvings (1903, 478). The first RCAHMS survey largely repeated Allen and Anderson’s description and typology a few years later (1914, 15).

Although the Ordnance Survey and Frederick Coles had identified ‘Trusty’s Hill’ to be a nineteenth century invention, local writers continued to attribute a legendary association of the site with King Drust well into the twentieth century (Maxwell 1930, 262). The story of Trusty’s Hill had clearly kept pace with a growing awareness and romanticism of the Picts, their historical figures and their symbols across Scotland in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This also fed into a wider narrative about of the ‘Picts of Galloway’ with the symbols being perceived as a physical link to this mythologised past.

Fig. 1.5. Coles’ 1893 Plan of Trusty’s Hill. We are grateful to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland for permission to reproduce this illustration

Fig. 1.6. Allen and Anderson’s 1903 depiction of the Pictish Symbols at Trusty’s Hill. We are grateful to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland for permission to reproduce this illustration

The first archaeologist to examine the Trusty’s Hill symbols was C. A. Raleigh Radford. Radford considered the horned head to have been retouched in modern times but thought the form to be of genuine antiquity (1953, 237). He compared the similar relationship of the Pictish symbols at Trusty’s Hill to two other non-Pictish forts, Dunadd in Argyll and Edinburgh Castle Rock, which either contain or lie in proximity to Pictish symbols. Based on the reference in the twelfth century Life of St Kentigern by Jocelyn of Furness to a stone erected to mark the spot where King Leudon fell, Raleigh Radford postulated that these carvings commemorated Pictish leaders who had fallen in attacks on these fortresses (1953, 238). Radford classed the symbols as Class II, and considered them late seventh or early eighth century AD by analogy with likely Pictish raids in southern Scotland in the decades following the battle of Nechtansmere (1953, 239).

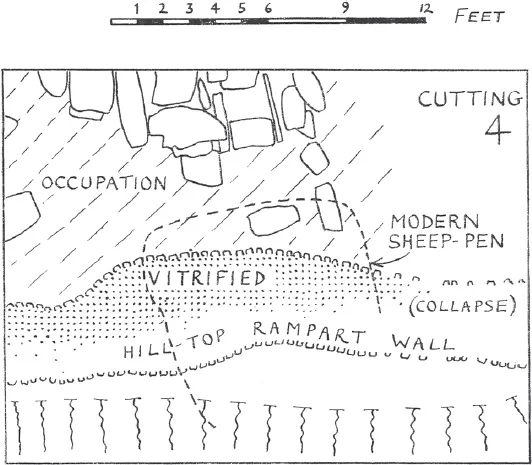

The first excavation of Trusty’s Hill was directed by Charles Thomas in 1960 (1961, 58–70). Charles Thomas’s interest in the site was encouraged by R. C. Reid (Thomas pers. comm.), then one of the editors of the Transactions of the Dumfriesshire and Galloway Natural History and Antiquarian Society, who had long advocated its excavation (1952, 163–64). Thomas’s team excavated seven trenches, including two within the summit of the hill, and surveyed a new plan of the site showing the excavation trenches (Fig. 1.7). The easternmost of these trenches, Trench 4, yielded a substantial amount of animal bones, from cattle, sheep and pigs, and charcoal from a dark occupation layer said to be 3–6 in (76–152 mm) deep (Thomas 1961, 63). The lower half of a granite rotary quern was found buried face down bedded in this occupation layer, which overlay a thin dark skin of old turf that itself covered bedrock an average of 18 in (457 mm) below the ground surface (ibid.). Sizeable blocks of flattish stone were also recorded across the western side of Trench 4 towards the interior of the summit enclosure. While none of these appeared to be in situ, the occupation layer seemingly respected their eastern edge. This edge was also sealed by the rubble of the collapsed rampart along the eastern side of the site which had fallen both inwards into the enclosure and outwards down the slope of the hill (Thomas 1961, 63–4; Fig. 1.8). Vitrification of the internal rampart core was revealed, particularly along its interior side, and a considerable amount of modern disturbance to the rampart was also noted here. Thomas noted that in this area the rampart had been truncated and overlain by a small collapsed structure constructed from stone robbed from the rampart (ibid.).

Thomas’s excavation of Trench 5, on the opposite western side of the summit, revealed the apparent basal course of a stone wall about 4 ft (1.22 m) in width that had collapsed outwards and down the western flank of the hill (1961, 63). A small cutting, Trench 7, was opened across a small platform on the north-western flank of the hill but revealed only a narrow collapsed wall and a thin layer of turf overlying bedrock (Thomas 1961, 64). Very little else of the interior was exposed as unrecorded sondages apparently revealed only bedrock (ibid.).

In addition to the vitrified ramparts, Thomas revealed another key feature, a waterlogged rock-cut depression lined with dry stone masonry symbols (Thomas 1961, 65–6; Fig. 1.9). This was located directly to the east of the entranceway, out with the summit rampart and opposite the Pictish inscribed outcrop. Thomas removed rubble and vitrified stone collapse from the summit rampart above to a depth of 3 ft (0.91 m) before water seeped in rapidly, confirming that this feature was a focus of surface drainage (ibid). Large granite boulders were exposed on a bedrock ledge immediately adjacent to the depression on the south side, and a further 3 ft (0.91 m) was excavated beyond this nearly to bedrock (Thomas 1961, 66). On the basis of this evidence, Thomas speculated that the feature was the remains of a small oval ‘guard hut’, measuring 9 × 11 ft (c. 2.74 × 3.35 m), with its southern and eastern walls founded on a course of granite boulders wedged into natural shelves of bedrock (ibid.). Thomas suggested that the foundations of the building lay approximately one foot above the original floor level in effect making this a sunken floored building (ibid.). The western side of this oval space was deemed to be the doorway but this was not clearly defined. A bank of stones emanating from the summit entrance as an out-turned stub bank blocked the possible doorway space entirely. The northern side of the supposed hut, cut into the hill slope, was defined by courses of flat stones arranged to form a semi-circular inner face almost four feet high. Thomas noted that due to rapid water ingress the floor of this oval space was reduced to a ‘soupy mud’, and while charcoal was noted, no artefacts were recovered.

Fig. 1.7. Thomas’s 1960 plan of Trusty’s Hill. © DGNHAS

Fig. 1.8. Thomas’s plan of Trench 4. © DGNHAS

Another cutting, Trench 3, was opened across a platform to the west of the entranceway on the other side of the Pictish inscribed outcrop from the ‘guard hut’, but Thomas was unable to penetrate the mass of rubble and vitrified stone that had collapsed on to it from the rampart above (Thomas 1961, 65). However, this trench did confirm that the bank that defined the western and southern edge of the platform comprised a mass of rubble and earth piled behind an outer revetment of dry stone with no inner revetting face.

Trench 1 examined the lowest lying of Trusty’s Hill’s enclosed areas on the southern side of the summit. This trench revealed that the lowest and southernmost step was natural and that to the north of this, t...